Author: Marshall Schott

Pilsner, Helles, Dunkles, Märzen, Vienna, Bock, Schwarzbier– all different in their own terrific ways, the one thing these beers have in common is the fact they are lagers. While quality commercial examples exist, including a growing number of domestic craft options, many homebrewers avoid making these delicious styles due to how convoluted and time consuming the process is. In addition to recommendations calling for yeast pitch rates nearly double that needed for ales, step mashing, and extended boil lengths, many believe genuine lager character can only be produced by following an already lengthened cool fermentation stage with an even longer period of cold conditioning. In New Brewing Lager Beer, Greg Noonan advises determining lager duration based on the OG of the beer, allowing 1 week for every 2° Plato (about 0.008 SG), meaning that a 1.050 OG Pilsner would require nearly 6 weeks of lagering once fermentation is complete. The hesitance is understandable.

I’d brewed a couple lagers using traditional methods, they came out great, but they tied up my fermentation chamber way too long. So, I began researching the history of lager brewing in an attempt to understand why they required so much time. What I noticed was that many of the methods accepted as convention seemed a direct emulation of those used by traditional lager brewers who didn’t have access to the technology we do today. It was almost as if the methods we adopted were based off of the assumption that lager brewers of yore specifically chose the process they did, as opposed to their processes being a function of the resources they had available to them at the time. Rather than adapting, we adopted, ignoring our sophisticated temperature regulators and treating our fermentation chambers like cool, dark German caves.

Able to turn ale around in as little as 2 weeks using a ramped fermentation schedule, and fully aware that my theory could be total shit, I figured I’d apply the same logic when brewing my next lager– start cool and gently raise the temperature to encourage a quicker ferment, then cold crash to just below freezing for a few days, keg, and force carbonate. Lo and behold, this quick lager method worked, the beers came out just as good as those I’d made in the past, but they were ready in only 3 weeks. I was sold and proceeded to share the method, eventually learning that others had been using similar techniques with the same success.

Of course, many questioned this approach, some more adamantly than others, convinced that a side-by-side comparison of lager beers produced using the traditional and quick methods would be the only good way to know if the differed or not. I agreed and finally decided to put it to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between two lager beers of the same recipe fermented using either traditional or quick methods.

| METHODS |

The reason it took so long to get to this xBmt is because we kept going in circles when it came to designing an approach that eliminated extraneous variables. We eventually agreed this was impossible and moved forward, making what we deemed the smallest sacrifices. Since quick lager advocates claim their method produces beer equal in quality to those fermented traditionally, we thought it best to compare beers that were ready in their typical time frames. What this meant was the quick batch wouldn’t even be brewed until the traditional batch was done with primary fermentation and had entered the lagering phase. In an attempt to keep things as organized as possible, since both brew days were identical, I’ll present them together and emphasize points of divergence.

For this xBmt, I figured a very simple recipe would make any differences more obvious to tasters.

Lager For The Lazy

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 24.8 IBUs | 2.9 SRM | 1.053 | 1.009 | 5.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.006 | 6.2 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (2 row) (Gambrinus) | 9.969 lbs | 100 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mt. Hood | 25 g | 60 min | First Wort | Pellet | 5 |

| Mt. Hood | 20 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bavarian Lager (M76) | Mangrove Jack's | 79% | 46.4°F - 57.2°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 70 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 84 | Cl 62 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I was concerned about potential differences in pitching rates propping liquid yeast in starters, so after consulting with the crew, I opted to pitch 2 packs of dry lager yeast into each batch. While my go-to is Saflager W-34/70, and despite the fact it’s the most popular lager yeast in the world, I refrained from using it for this xBmt due to reports that it’s actually closer to a hybrid yeast. Instead, I went with Mangrove Jack’s M76 Bavarian Lager yeast, which has a recommended fermentation temperature range of 45°F – 57°F/8°C – 14°C. I contacted Mangrove Jack’s seeking the source of this strain, which was fruitless though they did confirm M76 is a traditional lager yeast intended to be fermented at cool temperatures.

On the evening prior to the first brew day, I measured out the grains for both batches, placing the unmilled portion for the quick lager batch in a sealed bucket to await a future brew day before milling the other half. Note that the quick lager grains were also milled the night prior to that brew day exactly 5 weeks later.

Since I’d be using the batch sparge method for these 10 gallon batches, I collected precise amounts of mash and sparge water in separate kettles then adjusted them with the same amount of minerals and acid. I woke up at 5:00 AM on both brew days and promptly began heating strike water.

In order to ensure similar mash temperatures, it was important that I accurately measure the grain temperature to determine the proper temperature of the strike water, which BeerSmith made a piece a cake!

After mashing in, I allowed each to rest for precisely 60 minutes, stirring only once at the 30 minute mark.

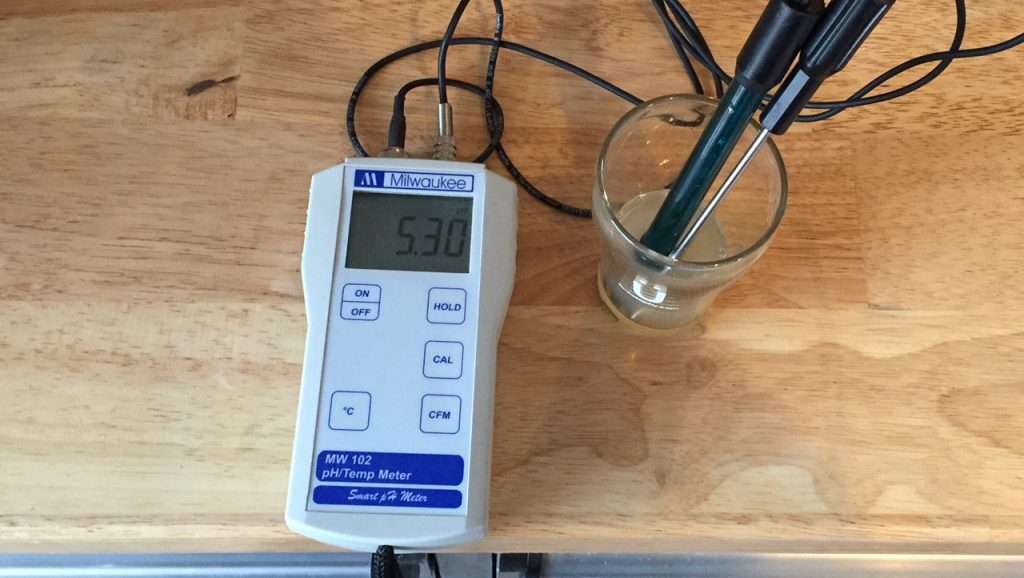

I pulled a small sample from each mash at 10 minutes in to check the pH was pleased to discover both hit my 5.3 target.

After the hour long mash rests were complete, I batch sparged to collect the same volume of sweet wort, which was quickly brought to a rolling boil.

During the 1 hour boils, I added the same amount of hops at the same times, then proceeded to quickly chill each wort.

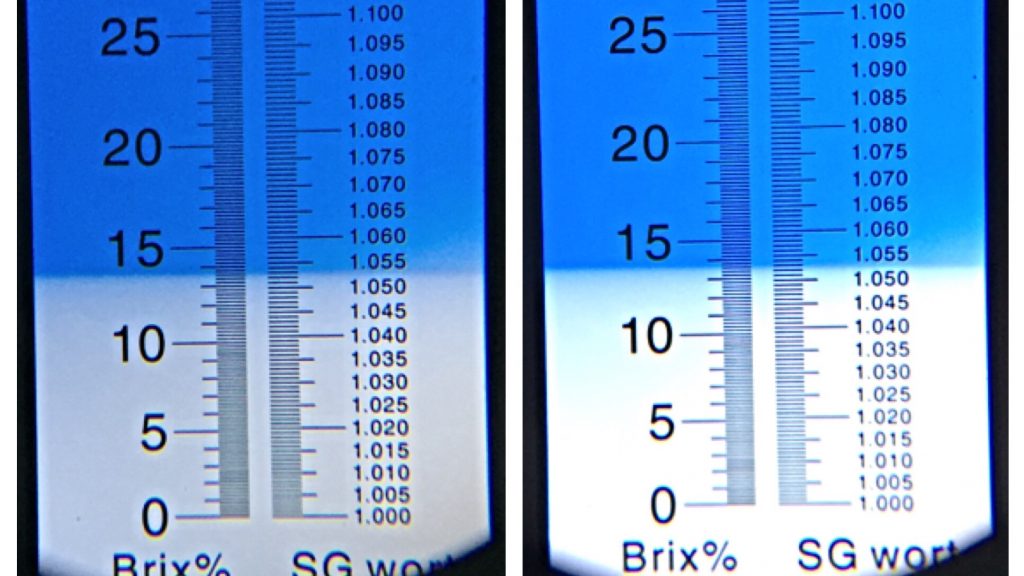

Thankfully, my groundwater temperature was the same on both brew days, allowing me to chill each to the same temperature (79°F/26°C) in a similar amount of time (10 minutes). Post-boil refractometer readings confirmed both batches were starting at the same OG.

Both carboys of wort were left for 10 hours in their own chamber set to 50°F/10°C, my target fermentation temperature, before receiving 2 rehydrated packs of Mangrove Jack’s M76 Bavarian Lager yeast.

And this is where the fun began…

In order to eliminate any chance of temperature compromising the data, the team decided it’d be best to let the traditional batch ferment at 50°F/10°C the entire time, going against the popular practice of gently raising the temperature toward the end of fermentation for a diacetyl rest. While activity was noticed within just 12 hours of pitching the yeast, the consistently cool environment made for a rather long fermentation period with a hydrometer reading 1 week post-pitch showing the beer had dropped a mere 0.011 SG points.

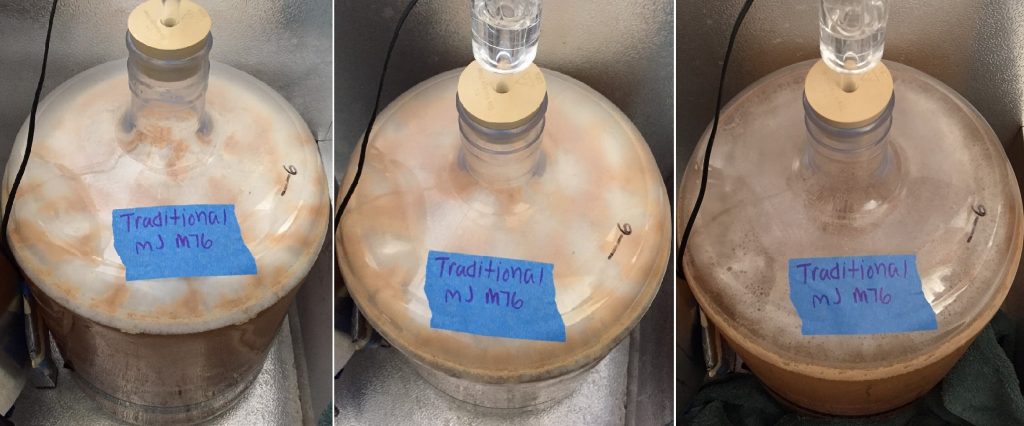

A cap of frothy kräusen hung around for weeks as the yeast slowly turned sugar into alcohol and CO2.

It took 24 days before the krausen on the traditional beer finally dropped and airlock activity ceased. An initial hydrometer measurement showed the beer had indeed dropped to the predicted FG, and with a second measurement 3 days later showing no change, I began gradually reducing the temperature of the chamber to 32°F/0°C.

It wasn’t until the traditional batch had been lagering for 1 week that I brewed the quick lager batch, exactly 5 weeks later. Again, in an attempt to reduce extraneous variables, we decided it’d be prudent to package the beers at the same time, meaning the traditional batch would be left to lager in primary while the quick batch was fermenting.

Fermentation took off equally as fast in the quick batch as evidenced by kräusen development within 18 hours. However, in contrast to the traditional batch, I began raising the temperature in the chamber after 5 days, eventually reaching 68°F/20°C just 1 week after being brewed.

As I’ve experienced many times before, all signs pointed to fermentation being finished just 12 days after the beer was brewed, with a hydrometer measurement verifying the predicted FG had been reached. I let the beer sit at the warmer temperature for 3 more days before taking a second hydrometer measurement that showed the FG hadn’t changed, and it just so happened to be the same as the traditional batch.

While I used to decrease the temperature of the beer gradually out of fear of stressing the yeast and causing off-flavors, I started going the even quicker route of immediately setting my controller to 32°F/0°C after hearing positive stories from other brewers, so that’s what I did here. Given the variable in question, I opted to forgo fining with gelatin and proceeded to keg both beers the following weekend, 8 weeks after the traditional batch was brewed and 3 weeks after the quick batch was brewed.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer and put under 40 psi for 24 hours before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. By the following weekend, with the beers carbonated and ready for serving, I noticed small difference in clarity between the lagers.

| RESULTS |

Data for this xBmt was collected on two occasions separated by 7 days, the first occurring in my garage and the second at a monthly Tulare County Homebrewers Organization for Perfect Suds (TCHOPS) meeting. A total of 31 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was blindly served 2 samples of the traditional lager and 1 sample of the quick lager then instructed to identify the one that was different. In order to achieve statistical significance given the sample size, 16 participants (P<0.05) would have had to correctly identify the quick lager sample as being unique. In the end, 17 tasters (p=0.01) made the accurate selection, indicating tasters were reliably able to distinguish a beer made using the quick lager method from one made with a more traditional fermentation schedule.

The tasters who were correct on the triangle test were subsequently asked to complete a brief evaluation comparing only the different beers while still blind to the variable being investigated. The traditionally fermented lager was preferred by 11 of the 17 tasters with another 4 preferring the quick lager batch and 2 saying they noticed a difference by had no preference. In conversations following completion with the xBmt, the most common comments had to do with how similar the beers were in general. Interestingly, one taster, still blind to both the variable and the style of beer, remarked that the quick method beer had a subtle sulfur note it that “makes it tastes more like a Pilsner,” while another taster noted the traditional batch has tasting “a little more sweet, less crisp” than the quick batch.

My Impressions: Upon returning home from the aforementioned meeting, I put myself through 6 semi-blind triangles and consistently, easily, identified the unique sample. To my palate, both beers had a noticeable white grape-like flavor that, based off of information from others, seems to be something people are experiencing with Gambrinus Pilsner malt. I’m not particularly a fan of this character, which was more strongly expressed in the traditional beer, thus my preference for the beer made with the quick lager method, in which I detected what I thought to be a very light sulfur component that made the beer more pleasant.

| DISCUSSION |

Even before I committed to doing this xBmt, whether or not quick lager methods produced qualitatively similar beers as those fermented with more traditional techniques wasn’t really my concern. Rather, I was more interested in my ability to make a beer I thought was delicious and had what I perceived as “lager character” in a shorter amount of time. While I completely understand and appreciate folks who wish to pay respect to those who came before us by sticking as rigorously as possible to traditional methods, it’s true my anecdotal experience using these heretically hastened techniques has been quite validating, leaving me almost convinced that extended fermentation and cold conditioning aren’t necessarily the key to achieving a divine lager beer.

The fact tasters were reliably able to tell the traditionally fermented lager apart from the one made using quicker methods 5 weeks later certainly supports the notion that either method has a unique impact on beer. And with a majority of tasters who got the triangle test correct noting a preference for the traditionally fermented beer, perhaps there is something to be said about taking a more patient approach when making lagers.

As for me, I’ve absolutely no plans to integrate extended fermentation and lagering into my brewing, primarily because I’ve always been happy with quicker methods, but also because I actually preferred the quick lager batch. As always, this xBmt made me even more curious about the variables involved in the brewing of lager beers and will certainly serve to motivate more exBEERimentation in the future!

What has your experience been with making lager beers? If you’ve used traditional and/or quick approaches, please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

52 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Lager Methods: Traditional vs. Quick Fermentation In A German Helles Exportbier”

I’d like to see the result if you used the gelatin finings. I haven’t made a lager using your approach yet but I will next time I make it. The one time I made a lager that I “rushed it” (only 2-3 weeks in secondary), it was great and I didn’t detect any off flavors compared to ones I’d left in the cold for months.

What is your verdict on the Mangrove Jack’s M76? Does it compare well to W-34/70?

I’ve yet to use a Mangrove Jack’s yeast I didn’t like. Given how clean 34/70 is and how seemingly clean the beers in this xBmt came out, I’d have to say they’re at least comparable. Perhaps a yeast comparison is in order.

I make more lagers using the quick method. My Kolsch takes around 25 days to finish while a quick lager takes me around 18 days.

What’s your temperature/days on the quick lager? That seems really fast.

50 for 3-4 days, raise to 68 over 2 days, leave for 3-5 days, crash to 30 and leave for a couple days, keg, carb, drink.

Great article (as always) Your previous post on this issue was really well timed – a few days into an IPL I was making as my first lager – which allowed me to divert this into a much quicker /warmer ferment with great results. This article has been a real prompt to get another IPL on the go…

Your website is my go to resource for all practical information – thanks a lot from sunny Scotland…

Great stuff. From what I remember of the genome sequencing papers, the family of yeasts that 34/70 belongs to retained more of the cerevisiae genome than did some of the other lager yeasts like wlp800. All lager yeasts are “hybrids” though.

I too wonder if gelatin would have narrowed or eliminated the differences. “Powdered time” as you guys call it.

34/70 is a bona fide lager yeast but it belongs to the Frohberg class of lager yeasts, all of which have one whole ale yeast genome (i.e. a diploid S. cerevisiae genome) in their DNA along with one whole lager genome (a diploid S. eubayanus genome). In contrast, Saaz group lager yeasts only have half an ale yeast genome (a haploid S. cerevisiae) mixed in with a whole lager genome. A couple of years ago this discovery led to claims that they two types of lager had separate origins, but now it looks like they formed from one hybridization but the Saaz group later lost a quarter of their genome in a mutation.

WLP800 may not be a true lager yeast. For one thing, it’s top-fermenting. Also, there was a recent paper in Cell (link below) pointing out that at least 10 commercial lagers are brewed with ale yeasts (S. cerevisiae), not true lager yeasts at all. The authors didn’t identify the strains in question for reasons of commercial confidentiality, but one of them was described as “Czech lager”. To my mind, this just further calls into question what a lager really is. I see it simply as a style of beer, not necessarily defined by the yeast or style of fermentation. If it tastes like a lager, it’s a lager!

Cell paper: http://www.cell.com/fulltext/S0092-8674(16)31071-6

I think I’m about 80-90 % with you on that. When I first started brewing my own beer (before taking a 10-year hiatus) I used to put the fermentation bucket in the corner of my unfinished basement. One wicked cold January I could not get my ale to ferment, even after sitting for ~3 weeks. Brought it up to my first floor, fermentation started almost immediately. Long story short, my brother thought I was serving him Old Style. I think some German brewers use lager yeast when bottle conditioning their hefe’s.

The sulfur note should fade with time, making the two beers more similar. Perhaps after after a few weeks more they would be indistingishable and equally clear, but then the quick lager wouldn’t really be quick.

Very interesting experiment, thanks for sharing.

I’d be more interested to know the results if you did initial fermentation in a similar fashion and then just “lagered” one longer.

Interesting! A significant result again on something a lot of people would not think would give one.

So, it seems clear that you can’t make the same lager using the traditional vs. quick methods, but you can make a really good lager using either process. The fact that they taste differently is not a surprise – would any 2 beers of any style that were made 5 weeks apart taste the same if the younger beer was just tapped? Of course not.

Your quick lager method seems to work just fine. You made a really good beer that most people don’t try to make because they think it takes too long. I’d say that this equals success.

It would be interesting to see if the difference was from the length of lagering time or the long cold fermentation. I’d be more likely to let a beer lager in the keg (my keezer holds one more kegs than I have taps) then to let a beer ferment for 24 days and if that makes the difference it would be a plus to making some lagers.

As always, great information.

Thank you for doing this test – I was hoping you would get to it.

One comment though, relating to your statement ” I refrained from using it for this xBmt due to reports that it’s actually closer to a hybrid yeast.”

All lager yeasts are hybrids. The group II lager yeasts, which include 34/70, retain most of the genetic material of the two parental strains. The group I lager yeasts are descendants of the group II lager yeasts, and have lost some (about 1/4th) their DNA.

Hey Bryan, I’m fully aware that all lager yeasts are hybrids generally classified into 1 of 2 camps. I avoided getting too much into this in order to (1) keep the article a readable length and (2) distract from the exBEERimental purpose. To be more clear and to the point, the reason I didn’t use 34/70 is because when I have for lager xBmts in the past, namely regarding ferm temp, a small number of readers voice concern that the reason temperature didn’t produce a distinguishable result is because the yeast isn’t a “true” lager strain. It’s bull, I know, but I’m also cool with integrating other yeasts. Cheers!

Paragraph 3, do you actually crash to just below freezing? That’s a cold, cold crash!

Yep, 30˚F is my standard cold crash temp for beers with 4.5% ABV or higher; anything lower and I stop at 32˚F to avoid potentially freezing the beer.

Cool…

I have tried the fast option twice. Both times I have been disappointed. I could detect an ester type sweetness on both occasions. I love the idea of fast lager, but its not for me.

Oddly, I’d say the traditional batch had more of what I’d say might be interpreted as an ester in this case.

I brew quite a few lager beers. I usually ferment my light lager at around 50-55 for 2 weeks, and then transfer to lager for 4-6 weeks depending on the beer, before kegging and consuming. I used to do the diacetyl rest thing with it, but one time I forgot,and didn’t do it. It turned out fine, and I haven’t done it since.

One thing you said in the article was you added 2 pkgs. of lager yeast to the wort. Lagers need large inoculations of yeast to ferment right. I usually make a 2L starter 3 days before brewing, and then cold crash and pour off the beer portion (actually I drink it). This usually initiates fermentation within 8-12 hours, and fermentation usually finishes up around day 8. It still stays in the fermenter till day 14.

I’ve never had a lager beer take as long as your ”traditional” beer to ferment out, and I ferment my Noble Pils clone down in the 40s.

Pretty coming for dry yeast. My liquid lager starters are usually ~3L and take off around 12 hours.

I notice that you did not do a protein rest. I’ve always read that a protein rest is needed when using pilsner malt. However, that does not seem to be your experience. Thoughts?

Perhaps with undermodified malt, but I’m a single infusion brewer.

Isn’t pilsner malt less modified than pale malt (=”undermodified”?)? Not that I think a protein rest is necessarily needed for pilsner malt anyway, as it is enough modified in the modern malts produced today.

There are less and more modified Pilsner malts, but I always end up getting a few more efficiency points from the Pilsner I use.

Enjoying a Märzen (Oktoberfest) that I brewed using the quick lagering method and love it. Did a (non-scientific) taste comparison to a Sierra Nevada Mahrs Bräu and definitely preferred the homebrew. Even with two ferm chambers, I hate to tie one up for months unnecessarily. The quick method allow me to enjoy a lager as soon as possible and also affords the opportunity to experiment and test new recipes without investing extra time. Completely agree with Marshall, I can’t see going back to extended fermentation and lagering when I could just be relaxing with a homebrew.

do a extract with steeping grains vs allgrain experiment

https://brulosophy.com/2014/07/21/extract-vs-all-grain-exbeeriment-results/

https://brulosophy.com/2016/01/04/extract-vs-all-grain-pt-2-comparing-recipe-kits-exbeeriment-results/

Won best of show this year out of 100+ entries with an American Light Lager fermented with your quick Lager (3-week’ish) method. To me it’s similar to shopping for TV’s side by side. At the store you can definitely see minor differences in color, brightness, etc between 2 brands, but once you choose one and install it at home it’s the best looking TV you’ve seen.

Either way thanks, appreciate this one. The only way for now that I’ll be able to realistically brew Lagers with my setup and patience level is with this quick method .

Congrats!!

what kind of yeast did you use?

In the first paragraph, I think that should be six weeks, not 12. 12.5P / 2 = 6.25

You’re right. How I missed that is beyond me. Thanks!

Do you not think that the extra time the ‘traditional’ batch had to lager would have an impact greater than the difference in fermentations? I’m not really surprised that more people enjoyed the beer that had been lagering longer. That’s how lagers work, they taste better if you leave them longer. Sorry but this experiment design is flawed. If you want a direct comparison you need the two beers to lager for the exact same time. You can’t draw any conclusions from this experiment at all.

Go do, amigo!

I second this idea. I suspect you’d have a better tasting lager, sooner, because it’d begin lagering sooner. Still, an excellent experiment.

We brewed two batches of OG 1.065 Oktoberfest on September 10th, fermented at 48, then ramped up to 65 when they hit 1.030 (75% to the expected FG 1.016) on the 16th. I’m going to pull another gravity sample on the 21st, and if it’s 1.016, going to cold crash, and then rack to kegs the 23rd or 24th.

For an October 14th wedding, we’ve brewed four batches of Belgian Dubbel, four batches of a Spotted Cow clone (cream ale), and four batches of a Zombie Dust clone (half a pound of Citra per 5G IPA). These two batches of Oktoberfest are surprise beers for the wedding, which if we keg them this weekend, will get only three weeks of laggering. If they’re good, they go. If you bring homebrew to a wedding in October, you have to bring homebrewed Oktoberfest, right?

Ive tried the method a couple times with a few seasonal strains and haven’t had the best of luck. So I generally stick to the traditional methods. I rarely am in need of a beer so the time isn’t really a factor for me.

However, It just so happens that I brewed a german Pilsner with 940? Mexican Lager on 9/11. By accident the temperature controller on my lager chamber was shut off 9/16 while iI was brewing another beer. When I turned the controller back on the next day the beer was at 61° I took a sample to assess the damage done and found the beer at just about FG with no noticeable off flavors. I kept the beer at 61° for the day then let it got to 65° the next day. Ill probably try to have it kegged by 10/1 and see what the home-brew club thinks.

I’m sure it’s great! One suggestion– don’t inform the club members of anything, just tell them it’s a classic lager and see what they think 🙂

Great Experiment and article as always. Question regarding the results, and maybe the approach. Age seems the be the one variable here that is the most obvious contributor to variance. When I started to read the article, I agreed with the approach in how you timed it for testing. But by the time I was done reading it, I did not. Regardless of the approach (fast lager/traditional) beer tends to modify with age. In the early months it will improve, in the late stages it begins to slide. The comparison of these beers was one that had, I believe, 5 weeks of aging on its side (it was just brewed, so early in the life cycle its only going to get better each week). If it could be timed where age of the beers post fermentation were the same for testing, or where a minimum of 3 months (Random I know) of aging was given to both I think you would see a different result.

My 2 bits

Still waiting for a proper exBEERiment of the low oxygen brewing method Marshall, no shortcuts!

“No shortcuts” is exactly why you haven’t seen one yet… the esoteric nature of LoDO makes performing it properly almost impossible.

In a properly conducted triangle test the panelists are given triplets AAB, BAA, ABA, BBA, ABB or BAB with equal probability (1/6). We wonder how the fact that these panelists were all given AAB might have effected the results. It is well known, for example, that there is a tendency to pick the cup in the center over the others. That is why it is important that the center cup be A in half the tests (approximately) and B in the other half.

I don’t think this oversight would have much effect on the conclusions. If going to the proper methodology resulted in one fewer correct identifications that would change the significance from 0.03 (16 right) to 0.06 (15 right). That still says the null hypothesis is weak.

Thanks for the fantastic comment, A.J., I completely see what you’re saying and have wondered how presentation of the samples might impact our results. It’s certainly something I’ll keep in mind that may inform future changes to our approach. Cheers!

Admittedly not performed in the most controlled or tracked a method, I personaly try to constantly alter the manner and order in which the samples are presented. No, I don’t ensure that equal amount of each sample set is evenly distributed as to how they are presented, but I don’t always go Red, Blue, Green, for example.

I like the idea but proper implementation may need to tighter controls and coordination.

Funny enough, a couple was in attendance at my last panel and the one of them used to teach statistics and the other ran a lab – they had similar suggestions.

I’m curious how you think this technique would effect aging rather than fermentation. I’m thinking of the case of Imperial Stouts which may ferment at ale temperatures but then I read a lot of people recommend aging the beer for months at lower temps. Could you get the same effect by aging for a shorter period if you let it stay at the same temp (or lower but not so drastic)?

I am a traditional German brewer but agree the process can be shortened. I as well like to start cold then ramp up from 48f to 55f and ferment until complete give a two day diacetyl rest and crash to 31f. I let it set for two weeks then rack off trub and force carbonate. One thing I’ve found is to let the chilled wort set over night and rack off the cold break before pitching. I think I get a cleaner beer.

A very Narziss approach. Lately, I’ve just been fermenting my lagers with traditional lager yeasts at ale temps. Working out better than I ever expected!

Great read… Very interesting Marshall, please could you bullet point the steps and a favourite recipe? Fancy giving it a go… Cheers!

SON OF A BITCH! THANK YOU!

I’ve read this post at least a half dozen times and and cited it numerous times in various online haunts. But I just wanted to thank you for something I just noticed.

I love a German Lager. I have no LHBS so I get my recipes by building them from Brewer’s Friend or ordering kits. One of my absolute faves is a kit from Austin Homebrew. However, I ordered some other stuff from one of the other suppliers and decided to order their German Pilsner kit. I alternate between these kit suppliers depending on what I need.

I assumed the kits were identical. However, I noticed a white grape-ish flavor in one of the batches. Or maybe it was there all the time but I didn’t notice until my son pointed it out then I could not get it out of my head. The next brew didn’t have that flavor. The one after that had it again. I chalked it up to oxygenation and have invested in some anti-O stuff because oxygenation sucks balls.

Welp, according to you, turns out its the damn Gambrinus malt. That makes perfect sense because that taste coincides with my order history from those suppliers. I’ve one more batch of grape wine cold crashing now and I will somehow have to get through it and will think of you with every sip.

So, again, THANK YOU. Gambrinus is forever off my list.