Author: Marshall Schott

One of the easiest ways to stretch one’s brewing budget is to buy ingredients in bulk, which can reduce the price of many of the most common hops by 50% or more. While that’s all fine and dandy, most homebrewers aren’t blowing through an entire 16 ounces of a single hop for a 5 gallon batch of beer, making proper storage techniques worthy of some consideration. With the commonly accepted wisdom that oxygen and heat are the enemies of hops, many homebrewers vacuum seal and store them in the freezer, a method that seems to work quite well based on numerous anecdotal reports.

In an effort to isolate the impact age alone has on hops, we performed an xBmt comparing old Willamette hops to fresher hops of the same variety, both of which had been stored under optimal conditions. The response when we shared that tasters were unable to reliably distinguish between beers made with either was barely mixed, with the large majority expressing some degree of surprise, while others offered speculative explanations as to why the beers were so similar. Around this time, I was contacted by homebrewer Ryan Casey who said he had a few varieties of old hops lying around including some 2005 Simcoe. Given the reputation Simcoe has developed for sometimes producing interesting characteristics, I chose that and asked for more details, which Ryan was quick to give:

This bag of Simcoe wasn’t opened at all until a couple weeks ago. It was in the freezer the whole time and I just opened it up for a Pale Ale I did. It was then resealed in the chamber vacuum and placed back into the freezer.

I received the bag of hops a few days later and noticed a couple things immediately– they were darker and smaller than I was used to, plus the bag appeared to have lost its vacuum seal. To be sure, I asked Ryan if the bag was airtight when he shipped it, he swore it was, which is when the purpose of this xBmt was settled.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between fresh hops that have been stored well and old hops that have not been stored well when used in beers of the same recipe.

| METHODS |

Since Simcoe is most commonly used to make hoppier styles, I designed a simple single hop American Pale Ale for this xBmt.

Simcoe Pale Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 59.6 IBUs | 5.6 SRM | 1.055 | 1.009 | 6.1 % |

| Actuals | 1.055 | 1.007 | 6.3 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, 2 row (Gambrinus) | 10 lbs | 85.11 |

| White Wheat Malt | 1 lbs | 8.51 |

| Honey Malt (Gambrinus) | 12 oz | 6.38 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simcoe | 12 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Simcoe | 30 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Simcoe | 30 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Simcoe | 30 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.6 |

| Simcoe | 120 g | 0 min | Dry Hop | Pellet | 11.6 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Diego Super Yeast (WLP090) | White Labs | 80% | 65°F - 68°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

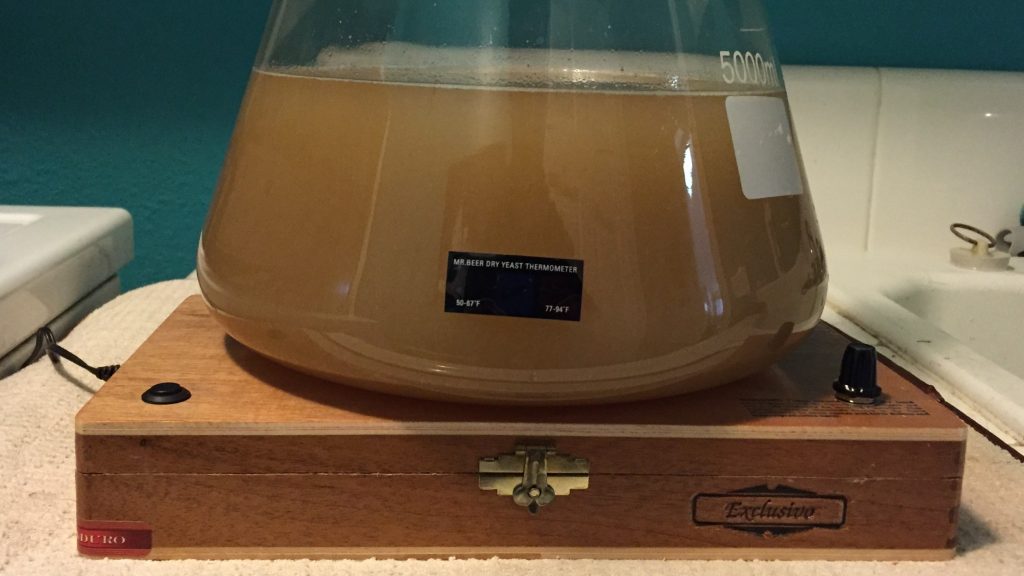

Using my preferred calculator, I made a large enough starter of WLP090 San Diego Super Yeast to split between two carboys with enough leftover to harvest for future use.

The following evening, after collecting the brewing liquor and making adjustments to achieve my target profile, I milled the grain for the entire batch.

Upon waking up the next morning, I immediately hit the flame under my kettle to bring the water to strike temperature before retreating inside to make some coffee.

About 20 minutes later, the water was ready, so I transferred it to my MLT and, after a brief pre-heat, stirred in the grains to hit my target mash temperature.

Since the variable for this xBmt would be introduced during the boil, I opted to perform a single 10 gallon MIAB batch sparge, the sweet wort from which would be homogenized and evenly split between two kettles.

I prepared the hop additions for each batch during the 60 minute saccharification rest and noticed the older Simcoe pellets were quite a bit smaller and darker than the fresh pellets. They also smelled… different.

On the bag the old hops were stored in, Ryan had indicated they were at 11.7% AA, which was only 0.1% higher than the 2014 hops. Similar to the first hop age xBmt, I chose not to deviate from the recipe by trying to calculate for AA% depletion over time, thus both beers received just about the same amount of hops. I started the old hop boil 20 minutes before the fresh hop to make managing my brew day easier. Both went for 60 minutes with the hops added at the same times in each before being rapidly chilled.

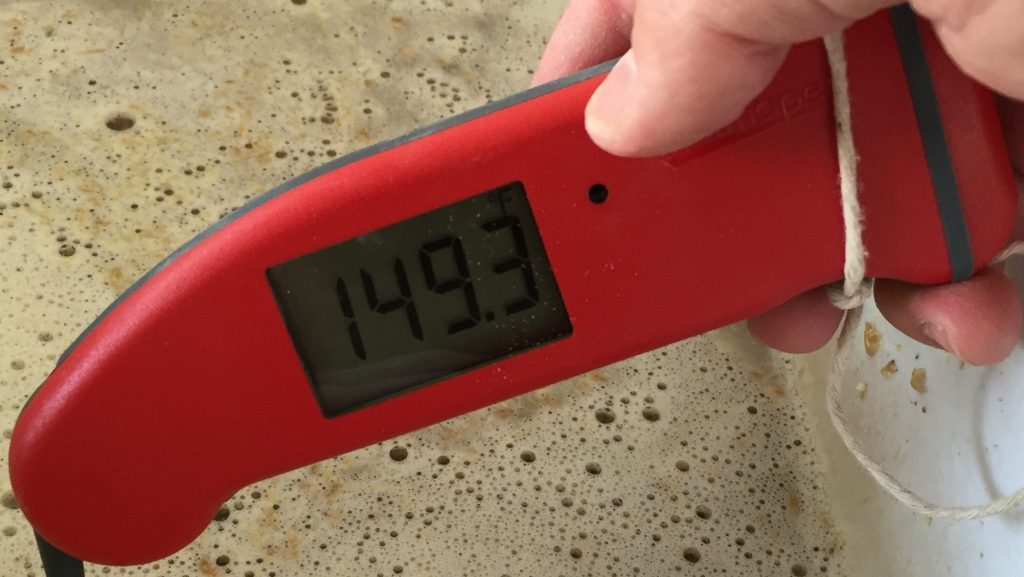

I transferred the slightly warmer than fermentation temperature worts into sanitized 6 gallon PET carboys and placed them into my cool fermentaiton chamber where they sat for a few hours to finishing chilling before yeast was pitched. Fermentation began and progressed similarly on both. I raised the temperature from 66°F/19°C to 72°F/22°C three days into fermentation and noticed waning activity three days after that, so I took initial hydrometer measurements, which matched those I took after another three days.

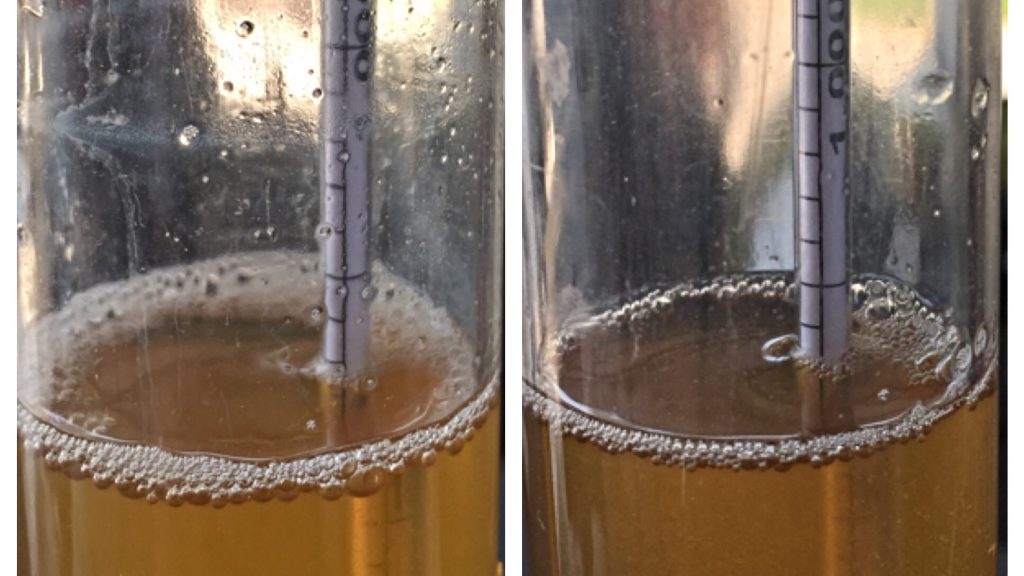

I proceeded to cold crash the beers, fine them with gelatin, then transfer them to kegs just short of two weeks from the day they were brewed.

The filled kegs were then placed in my keezer and hit with 45 psi of CO2 for about 20 hours before I reduced to serving pressure. Just a couple days later, the beers were nicely carbonated, beautifully clear, and ready for serving!

| RESULTS |

In all, 15 people of varying experience levels participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the fresh hop beer and 1 sample of the old hop beer then asked to identify the sample that was unique. Given the sample size, 9 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to correctly select the old hop sample as being different in order to reach statistical significance. A total of 13 tasters (p=0.00003) – all but two – accurately identified the unique sample, meaning this panel was indeed able to reliably distinguish a beer made with 10 year old hops that were stored in less than ideal conditions from one made with fresher hops stored well.

For the first time since I’ve been doing these things, every single taster who made the correct selection during the triangle test endorsed the beer made with fresh hops as being the one they preferred, using terms congruent with Simcoe hops– citrus, pine, resin, delicious. Easily the most common comment about the beer made with old hops had to do with how harsh it was, with tasters reporting a very sharp bitterness that lingered long after the sip was swallowed… or spit out.

My Impressions: From the moment I first opened the bag of old hops on brew day, I was pretty sure there’d be a difference between the beers. I’ve heard some describe poorly stored hops as “cheesy,” which I didn’t get, but rather a strong wet hay-like grassy aroma that wasn’t pleasant at all. The fresh hops smelled like what I expect from good Simcoe. In both cases, the finished beers followed suit. Frankly, I couldn’t stomach the old hop beer, it was horredous, to the point I actually felt bad serving it to participants. The beer made with fresh Simcoe was good, slightly one dimensional, but certainly not a dumper… like the old hop batch.

| DISCUSSION |

The results of this xBmt provide support for the idea that proper storage techniques may prolong the life of hops, in particular reducing the amount of oxygen the hops are in contact with. The issue then turns to what caused the old hops to be so different than the fresh hops. While it’s possible Simcoe hops have simply evolved over the last decade, hunch is the real explanation has to do with a lesser known hop compound known as beta acid.

In an effort to avoid regurgitating information that’s been written about numerous times elsewhere, I’ll refrain from going too deep into hop chemistry, but I think it’s relevant enough to touch on. Whereas alpha acids require heat to isomerize into the bitter iso-alpha acids we know so well, beta acids are known to become bitter when introduced to oxygen, most often as a result of poor storage. And it’s well documented that oxidized beta acids impart a bitter character known to be harsher than the bitterness that comes from alpha acids. Sound familiar?

There’s a reason hops come in nitrogen flushed and vacuum sealed bags. I recently drank a beer made with 5 year old Centennial hops that had been stored well, it was fantastic and could potentially have been indistinguishable from the same beer made with fresher hops. I’m compelled to believe this would not have been the case if the hops had been stored in a less ideal environment. As such, a vacuum sealer seems cheap insurance for those who prefer buying hops in bulk.

If you have any thoughts on this xBmt, please share them in comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

18 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Using Old Simcoe Hops Has On An American Pale Ale”

vacuum sealers sometimes appear to work and then a small leak lets in air very slowly. i switched over to using mason jars with the lid sealing attachment

Aaron – I’ve had that too, with about 1/3 of the bags I had sealed.

In hindsight I think it happens when I try to remove the plastic seal bag from the machine’s burner too soon, not giving it a “pause” to cool… I’ve also doubled up by sealing each side 2 times. With my new procedure…No More Problems experienced with seal!

I finally got fed up with the bags. I think i’ll just switch over to the mason jars if I can find the room in my freezer. it is fool-proof. I also had a couple of brownish kind of burned spots on the heating strip on my seal-a-meal that seem to give sealing problems, maybe they get too hot or not hot enough or something.

Do you tend to put the whole bulk bag of hops in one big bag, and reseal/vacuum the bag each time you take out a portion of the hops for a beer?(if you don’t do this, ignore the below)

I could see the bags getting wear and tear as you take them in and out of the freezer, cut open a small hole to pour from, and re-vacuum and re-seal them, I could see some small holes working their way into the creases in the bag.

Usually when I get a new bulk bag of hops I leave them all in the factory bag until I need them for the first time, then I break up the entire amount of hops, usually I split up 6-8oz into half ounce bags, and then the rest into 1oz bags. So my centennials I have 12-16 half ounce charges in bags which covers most late additions on non-IPA beers, the 8-10 1oz bags cover the late additions for IPAs and other hoppy styles.

It takes a little more prep work (measuring out the correct sized bags and sealing the ends/sides if you cut the bags in half to get more square shaped bags) but you do end up with nice little bags that, you don’t need to re-measure later, “Oh I need 2.5oz of centennial for this APA I just grab 2 of the 1oz bags and 1 of the .5oz bags”. I’m partial to not having to handle glass as much as possible. (yeah, also, I can see this may end up wasting a little more plastic which sucks, but any dropped mason jars REALLY sucks)

That’s closer to how I do it… Measure out 29g of hops – closer and more accurate way on my scale to measure 1 ounce (it’s just over). Divide all like that and then with my “new” process it works great. (Old process wasn’t bad either but some bags got some air back into them – which is not what we want…)

I found that most of my sealing problems were with bags that I had cut and resealed again, and it was hop debris and yellow lupelin crystals on the sealing surface that allowed the leakage. Once I cleaned the plastic thoroughly before sealing I had no more problems..

Aaron,

you are not really getting rid of the oxygen with a Mason jar. I’m not sure how big a vacuum a sealer pulls but it’s not close to a perfect vacuum. Part of the benefit of bags is that they physically displace most of the air. So if you are going to use jars you should also purge the jar, preferably with nitrogen but at least CO2.

I am pulling mine down to about 25 inches of mercury. At least I know that the oxygen that is the jar is all that is left to react vs. the bags that end up leaking and adding constant oxygen exposure to the hops. I’ll see how the jars go.

Very interesting. Not having room in my freezer to store all my hops, I vacuum seal all my hops in 100g bags and re-vacuum them as soon as possible after using. Given that hops are generally not frozen in the supply chain, I assume that removing oxygen is the main factor in preservation, though cold temperature slows down all reactions and preserves alpha-acids. It would be interesting to compare a home-vacuum-sealed pack that has been stored at room temperature to a similar pack that has been stored in the freezer for a few years. What are your views on the importance of freezing, if they are vacuum sealed?

From some of the books I’ve read, temperature plays a more important role than oxygen, there was a test where non vacuum sealed hops were frozen and vacuum sealed hops were kept at room temperature, and the frozen hops came out tops when measured later.

Let’s not forget we are dealing with hops here that are 10+ years old!

The same hop from two different farms can taste and smell different. Simcoe is actually notorious for this.

While I want to believe that age made the distinction, what popped into my head was year-to-year, let alone farm to farm, crop variability.

Could be, replication is the only way to come closer to an answer. For what it’s worth, if the 2005 crop tasted the way that old hop beer tasted, I beyond shocked it got as popular as it is. I was drinking Simcoe beers back then, they did not taste like that beer. Blegh!

There is also possibility that the hops are from different farms and therefore it will have an effect on taste also. But surely the 10 spent years will diminish the flavour. It would be interesting to see a comparison between well stored and badly stored hops from same hop batch. That would give more data how the storage conditions effect on quality. I’m sure that someone has made such a test but haven’t seen it yet.

Still nice job! I just subscribed to your blog via Feedly. Cheers from Finland 🙂

The first time I used BIAB I had really low efficiency. I think it was because the grind was to course. A lot of literature suggests that double grinding will increase the efficiency for BIAB beers. How were the grains crushed for this eBmt?

I ran them through my MM3.

I split out my larger packs of hops when they arrive into ~100g packs and vacuum seal them in Mylar bags but I add a couple of oxygen absorbing packs in each one then store them at ~32F. Those oxygen absorbing packs are used by preppers to keep stored food fresh.