Author: Malcolm Frazer

Belgian brewers are known to utilize an appreciable amount of simple sugar in their beer to achieve that signature drinkability, a culmination of several factors making for a beer that’s dry and pleasant to drink despite its high OG. The concept is accepted by many as paramount to a well executed Belgian beer and is covered extensively in Stan Hieronymus’ seminal tome, Brew Like a Monk. Sugar, in all of its various forms, makes appearance not only in high gravity Belgian styles, but many other beers as well. For example, British brewers have quite a history of using it in their beer, and of course more recently, sugar has come to be viewed as a key ingredient in higher OG IPAs, used to increase attenuation and ABV while contributing to lighter body. Sugar is great stuff!

Many recipes haphazardly include sugar on the ingredient list with nary a mention of how it should be used, leading many to simply add it all in one fell swoop. Sometimes it works, but sometimes it doesn’t. After experiencing a few high OG stalls myself, my research for potential solutions led me to a method involving adding sugar to the fermentor in staggered additions. The logic behind this practice is it allows the yeast to progress through the lag and initial growth phases at a lower gravity where the diet consists mainly of familiar malt sugars and nutrients, thereby reducing initial stress on the yeast; once fermentation is kicking along, the sugar is then added incrementally over a period of time. Besides reducing the purported risk of the yeast exhausting itself on a large charge of sugar, rendering it incapable of completing its target mission, it’s been claimed this method can produce less undesirable phenols, esters, and especially fusel alcohols . Made sense to me, so I integrated it into my brewing and never looked back.

Until recently…

I began to wonder if it was the staggered sugar additions that were responsible for my new found attenuation successes, or if perhaps it was due to something else. Is this method I’ve employed for years now actually making a difference?

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between 2 Belgian Golden Strong Ales of the same exact recipe where one had all of the recipe’s sugar added at the beginning of fermentation and the other received 3 staggered additions.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I made an 11 gallon batch of Belgian Golden Strong Ale that would be equally split post-boil between two fermentors.

Belgian Golden Strong Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 gal | 75 min | 29.0 IBUs | 4.3 SRM | 1.078 | 1.006 | 9.5 % |

| Actuals | 1.079 | 1.004 | 9.9 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pilsner (2 Row) Bel | 24 lbs | 84.96 |

| Aromatic Malt | 4 oz | 0.88 |

| Cane (Beet) Sugar | 4 lbs | 14.16 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 35 g | 75 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Saaz | 28 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

| Saaz | 14 g | 1 min | Boil | Pellet | 3.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgian Golden Ale (WLP570) | White Labs | 76% | 68°F - 75°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

In an effort to avoid introducing extraneous variables, I elected not to alter the pitch rate between the batches despite the differences in initial OG. I made a 2 liter starter about 24 hours in advance of my brew day with a targeted yeast cell density appropriate for the OG of the single dose beer.

I then prepared my water and grains the night prior to brewing.

My wife began heating the strike water an 1 hour before I got home from work. Once home, I had my lovely assistant help me mash in. While I’d targeted 148°F/64°C, I failed to compensate for the super cold weather of Western, PA and ended up a bit lower than expected. I wanted this beer to be dry anyway, so we called it good!

I took a pH reading about 15 minutes into the mash and, thanks to the great Bru’n Water Spreadsheet, I was barely a hair under by target of 5.4 pH.

To ensure a very fermentable wort, the low mash temp was paired with a 90 minutes mash length. Family dinner and toddler dancing commenced, then it was time to proceed. I collected the wort and brought it to a vigorous boil, adding hops at the appropriate times.

Despite recent xBmt results suggesting shorter boil lengths don’t seem to produce DMS, I extended the boil to 75 minutes as a security measure, as less modified floor malted Bohemian Pils malt made up a large portion of the grist. Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort to 62˚F/17˚C thanks to my bitter cold groundwater, evenly split it between two carboys, ensuring each received a similar amount of kettle trub. It was at this point I also took an OG reading.

Both carboys were placed into my fermentation chamber regulated to 64°F/18˚C. I pumped each full of equal doses of oxygen then split and pitched the yeast starter.

The yeast was apparently ready to work, as obvious signs of fermentation were present barely 24 hours later. Besides developing a kräusen sooner, the single dose batch was also slightly warmer than the staggered dose batch at this point. It was at this point I added the first of 3 doses of sugar, 1/3 the amount added to the single dose batch, to the staggered dose beer.

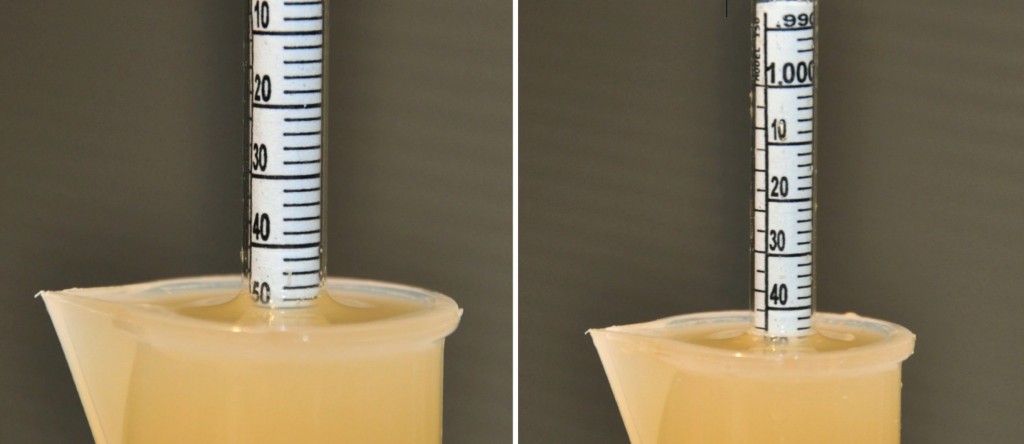

The staggered dose batch developed a kräusen a few hours later. The next day, about 48 hours post-pitch, I took a hydrometer reading prior to adding the second dose of sugar to see how things were progressing.

I added the third dose of sugar to the staggered batch after another 24 hours then let it go a few more days before signs of active fermentation diminished. The temperature had risen to 68˚F/20˚C at this point, it was time to measure the final gravity.

Likely a non-issue, I was a little surprised to discover the single dose beer had fermented 0.001 SG lower than the staggered, it left me even more interested to see if there would be a perceptible difference in flavor and aroma! I cold crashed the beers, fined them with gelatin, then racked them to kegs.

After a few days on gas, both looked good enough to drink when it came time to present them to tasters!

| RESULTS |

A total of 37 people participated in this xBmt including numerous BJCP judges, professional brewers, experienced homebrewers, and craft beer drinkers. Each participant was blindly served 2 samples of the single dose beer and 1 sample of the staggered dose beer then instructed to identify the one that was different. In order to achieve statistical significance given the sample size, 18 participants (p<0.05) would have had to correctly identify the unique sample. In the end, only 16 tasters (p=0.10) made the accurate selection, indicating the beer made with a single addition of sugar at the beginning of fermentation was not reliably distinguishable from the same beer made with 3 staggered sugar additions during fermentation.

The 16 participants who were accurate on the triangle test were instructed to complete brief comparative evaluation of just the 2 different beers, remaining blind to the variable being investigated. Since the results did not prove statistically significant, this information should be interpreted with caution, as it’s arguably meaningless. Overall preference was evenly split between the samples with 7 and 6 tasters preferring the staggered and single dose batches, respectively, while the other 3 tasters indicated they perceived a difference but had no preference. When asked to select the sample they believed was produced utilizing the staggered dose method, 9 tasters (53%) guessed correctly and the other 7 (47%) did not.

My Impressions: Initially, I was unable to readily distinguish these beers from each other with a performance rate of 50% on my first “blind” triangle trials. However, telling them apart seemed to become easier after some maturation time and as the beers warmed in the glass, with my accuracy on last 3 triangle attempts improving to 100%. I perceived the single dose beer as having an ever so slightly bolder ester profile, though it was still very pleasing, and I felt the intensity of the alcohol sweetness, mouthfeel, and warming created a small but noticeable difference. Ultimately though, without being tipped off as to the variable, it’s possible I wouldn’t have noticed any differences, they were so close.

| DISCUSSION |

The mere fact trusted homebrewing authorities began endorsing the use of staggered sugar additions during fermentation suggests to me there is some utility to the practice, and based on my own anecdotal experience, it does seem to reduce the risk of the dreaded stalled fermentation. Still, I expected these beers to be more different than they were, in terms of both measurable and perceptible qualities. The fact they weren’t leaves me wondering if staggered sugar additions during fermentation isn’t another insurance measure, as there are plenty of anecdotal reports from professionals and homebrewers alike swearing it has helped in their high OG brewing.

While these results ought not be viewed as the final authority on the matter, I’ll admit to feeling more inclined to return to adding all of the sugar in a single dose, not because of any qualitative impact, but out of my desire to reduce the brewing task load- 1 dose is easier than 3. However, I’m left wondering if there’s a point at which staggered additions start to show benefits, maybe a higher OG or certain yeast strains. And yet again, the xBmt idea list continues to expand!

If you have any thoughts on this xBmt, please don’t hesitate to leave them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

| Read More |

18 Ideas to Help Simplify Your Brew Day

7 Considerations for Making Better Homebrew

List of completed exBEERiments

How-to: Harvest yeast from starters

How-to: Make a lager in less than a month

| Good Deals |

Brand New 5 gallon ball lock kegs discounted to $75 at Adventures in Homebrewing

ThermoWorks Super-Fast Pocket Thermometer On Sale for $19 – $10 discount

Sale and Clearance Items at MoreBeer.com

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

33 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Sugar Additions: Single Dose vs. Staggered During Fermentation In A Belgian Golden Strong Ale”

Malcolm, great xbrmnt, I think your last two sentences sum it up the best for me too… now I have more questions

Ain’t that the truth!

Great read Malcolm. Maybe a hybrid approach? Instead of adding sugar at the beginning, add after kräusen has formed. That way the yeast start out on maltose, have had a chance to grow? Just a thought.

I wonder if the staggered addition of sugar would allow for a smaller starter size or the addition of only one package of dry yeast?

That was one of the many advantages I had heard some years back. Just as you hinted, if doing a very large OG beer you could POTENTIALLY not have to make a massive starter.

What is that red film you have over the carboys? Is that some kind of alternative airlock?

Ahhhhh, hard to tell in the photo, sorry for the confusion, but those are plastic cups. I use them as covers while filling carboys, adding O2, and often until fermentation get going. I had red duct tape on them in these photos to prevent them from getting knocked off.

I just brewed a tripel yesterday. I’ve gotten tired of messing around with my beer all of the time, so I opted for a single dose of sugar. Glad to know I won’t be making swill!

Good luck! I bet it’ll be fine.

I haven’t done cold-wort sugar additions before. I’m assuming you made a syrup?

Yes, a syrup was made in this instance. I’ve added the dry sugar before without much issue bit didn’t want to risk it this time because I had people waiting on me for the article. It was also easy to divide and I was less concerned of it “piling” up in the bottom of the fermentor among the trub etc.

Sorry if I’m just missing it, but did you mention anywhere how you added the sugar? I can’t actually see when you added it to the single dose batch, and for both batches I can’t see where you say how. Did you just pour it straight in, or mix it with boiled/cooled water first?

NP, a few people mentioned that it wasn’t clear in that regard. Sorry bout that.

From the Purpose Statment: “To evaluate the differences between 2 Belgian Golden Strong Ales of the same exact recipe where one had all of the recipe’s sugar added at the beginning of fermentation and the other received 3 staggered additions.”

Probably should have mentioned it more specifically. We’re making an effort to be more concise and my wordy ass makes it hard for Marshall when he edits! Lol.

4 lbs of sugar added to 500 ml of water. Water was brought to a boil. Held at 190 F ish for a brief period. Covered with canning lid. Chilled.

Half went into the Single Dose beer right after O2 and while adding yeast.

Other half was added in 3rds. First addition was after active fermentation, next two were 24 hrs apart.

Please let me know if you have further questions.

great experiment and also something I have always wondered about. I’ve always done this with saison, out of the reputation for WLP565 to quit. I might try to split the batches next time and dose staggered versus once.

PS, the beer was great

Hey Dave,

As always, thanks so much for the support! Glad you found the beer to be ok but I’m even more glad to have you come out and participate. See you soon.

Definitely a very interesting result.

Reading the title of the article I said “oh this will definitely have a statistically significant result”. Then I read the sentence where you weren’t going to change the pitch rate for the staggered beer which makes perfect sense and I said “I was wrong I bet it’ll be close but there won’t be a significant difference”.

I know 2 variable xbmts don’t happen but I’d be interested in seeing the same sugar test but with vitality starters/standard starter being used. I think a lot of folks like myself begin using the staggered sugar additions to deal with equipment limitations on our pitch rates.

“Then I read the sentence where you weren’t going to change the pitch rate for the staggered beer which makes perfect sense and I said “I was wrong I bet it’ll be close but there won’t be a significant difference”.”

Wouldn’t conventional wisdom suggest that by NOT altering the pitch rate there would a greater chance of a delta? Or am I missing something?

Well, I guess that had more of a potential if I had sized the pitch for a 1.060 beer, so that the 1.079 beer was further underpin cheddar – maybe that’s where you were going?

Ah yeah, I was saying if the pitch rate was the same for both beers but on the lower end. Due to equipment limitations it’s tough for me to hit the pitch rates needed for a 1.090 and up belgian beer (I can split and make multiple starters but it just starts to get cluttered). So if I start with a much lower OG by keeping the gist of the sugar out of the boil, I can get away with a starter sized for a much smaller beer (or it’s a much smaller under pitch).

For some reason in my big dumb brain I assumed the pitch would be sized smaller to the staggered addition beer. Which of course (I assume) would cause a beer to beer very different since the under pitch on the single dose beer would be huge in comparison (even though the vitality starter xbmt showed that yeast health is sometimes as important or more important than cell count).

Hi Malcolm

Maybe the benefit is not necessarily a different finished beer assuming that all goes well (as yours did) but a process which may be more robust to less scientifically minded home brewers preferences?

In your case as both beers fermented out fully then there is no benefit. But for those who don’t pitch adequately maybe there’s something to be had?

Just spitballing but the conclusion is not necessarily that there’s no benefit, but that with a certain group of variables controlled that there is no benefit

Small differences (not significant) could be due to effect on fermentation temperature. Not massively far from significance this one.

Assuming there is a difference (disclaimer due to not achieving significant results), I’d challenge back with “chicken or egg” analogy. It was warmer because of more sugar, which made more yeast, which made more heat (also all assumptions).

Yes, indeed.More sugar -> more heat -> more yeast activity. That gives you some links to work that are fairly well understood. I’d assume that if in the larger sugar addition the heat was controlled for (attempered somehow) there would be definitively no difference. .10 is the kind of likelihood where you consider rerunning an experiment and double check nothing quite messed with it. On the other hand, the more you re run it, the more likely you are to have a significant result by chance.

Jkaranka,

Temp was controlled this way – carboys were placed in freezer/ ferm chamber about 2F less than desired Ferm temp. The wort that had a Single large sugsr dose was just the first to warm up (activity) and the second one had activity a few hrs later.

Would you consider re-doing this experiment using Belgian candi syrup instead of sugar that was then turned into a syrup?

Potentially. Most suggestions and ideas are at least discussed and considered.

I do not really believe that Belgian Candi-type syrups/ sugars are not required or beneficial. That written, I am almost always willing to be proven wrong. I’m used to it! 8^).

A very interesting result, but it introduces a few questions. I wonder what would happen in a higher gravity situation, say like a 120 Minute IPA clone. Or, I wonder if it makes a difference if you add sugar initially vs. after initial fermentation is complete.

I was wondering the same thing. One of the benefits to adding incrementally in that situation though is that you can keep adding sugar until fermentation completely stalls. i.e. if you don’t know the limit to what the yeast will attenuate, by adding sugar in small increments you limit the risk of stalling with huge amounts of sugar still in your beer. There may also be more to the incremental approach too with extremely high gravity beers as the yeast health starts to be a real concern, but I don’t have the experience to speculate what that might be.

Always more questions! Appreciate you adding to the conversation. The issue of when such additions (in relation to gravity) may have influence is one we’d like to explore.

I *could* offer my hand at it, if you Brulosophers are willing. I’ve considered volunteering myself to open a Portland chapter, but I never got around to emailing Marshall ????

Great write-up! The book “how to brew” by John Palmer says the reason for adding sugar after fermentation has started is that worts with >15% sugar can prevent yeast from developing the enzyme which metabolized maltose. The yeast find it easier to metabolize the sucrose or dextrose, so they start with that and never move on to the other more complex sugars present. So, when using >15% sugar, add some or all of the sugar to the fermenter after the yeast has had a chance to developed the enzymes for all the fermentable sugars present.

– The reason I do a sugar addition is to dry out the Belgians and add the small % bump. –

– The reason to add it several days into the ferment is explained in the last comment from Mark George.

– The utility of it is that it can also prevent a stalled ferment which is a real drag on a higher beer.

What I do is boil the sugar with some water to make a syrup, keeping a lid on it towards the end to keep it sanitary. Then I dump straight into the fermenter. The thermal equilibrium is near instant since you are only dumping a couple quarts (if that) into 5 -15g depending. The idea of staggered additions is interesting, but I like to leave the beer alone and not mess with it so one seems prudent.

Main reason I add sugars during fermentation: to avoid having to make a yeast starter.