Author: Matt Del Fiacco

While sealing the fermentation vessel and affixing an airlock or blow-off tube to it is standard practice these days, it’s relatively new within the brewing world. Historically, fermentation occurred in loosely covered or even entirely open containers, leaving the beer exposed to whatever might be floating around the brewery, a thought sure to incite anxiety in some modern brewers.

However, open fermentation is still practiced today by brewers around the world, not many, but those who do often note it as positively influencing beer characteristics, some citing the lack of back-pressure as the primary factor. One example is Anchor Brewing who takes pride in being “the only American brewery that still employs open fermentation on a production scale,” which they believe contributes to their signature character.

Slightly more common among brewers in the UK, open fermentation is believed to encourage a more characterful ester profile, an important component of English ale, and also lead to improved attenuation. In fact, the revered Samuel Smith’s Brewery still use the Yorkshire Square to ferment in, a unique vessel that leaves the fermenting beer exposed to the environmental air.

With no experience open fermenting and as a lover of traditional English ale, I jumped at the opportunity to put this variable to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the difference between a British Golden Ale fermented in a closed vessel and one fermented in an open vessel.

| METHODS |

With claims that traditional English ales were fermented in open vessels, I went with a classic British Golden Ale recipe for this xBmt.

Flamel

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 gal | 60 min | 29.3 IBUs | 3.8 SRM | 1.042 | 1.010 | 4.2 % |

| Actuals | 1.042 | 1.011 | 4.1 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Golden Promise (Simpsons) | 5 lbs | 60.15 |

| Pale Malt (Weyermann) | 2.75 lbs | 33.08 |

| Wheat, Torrified (Thomas Fawcett) | 9 oz | 6.77 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 9 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 12 |

| Cascade | 34 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.5 |

| Cascade | 62 g | 0 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| House (A01) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 62°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Yellow Balanced in Bru’n Water Spreadsheet |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Imperial Yeast A01 House is a classic English ale strain I thought was appropriate for this particular variable, so I got a starter of it going ahead of time.

Having collected my water the night before brewing, I started my brew day off by adjusting it to my desired profile and turning on the elements to heat it up.

I then proceeded to weigh out and mill 2 identical sets of grain.

When the water was at strike temperature, I mashed in and turned on the recirculation pump before checking the mash temperature.

Each batch was mashed for 60 minutes, after which I removed the grains and let them drip into the kettle to reach my target pre-boil volume.

While waiting for the wort to heat, I weighed out the hops.

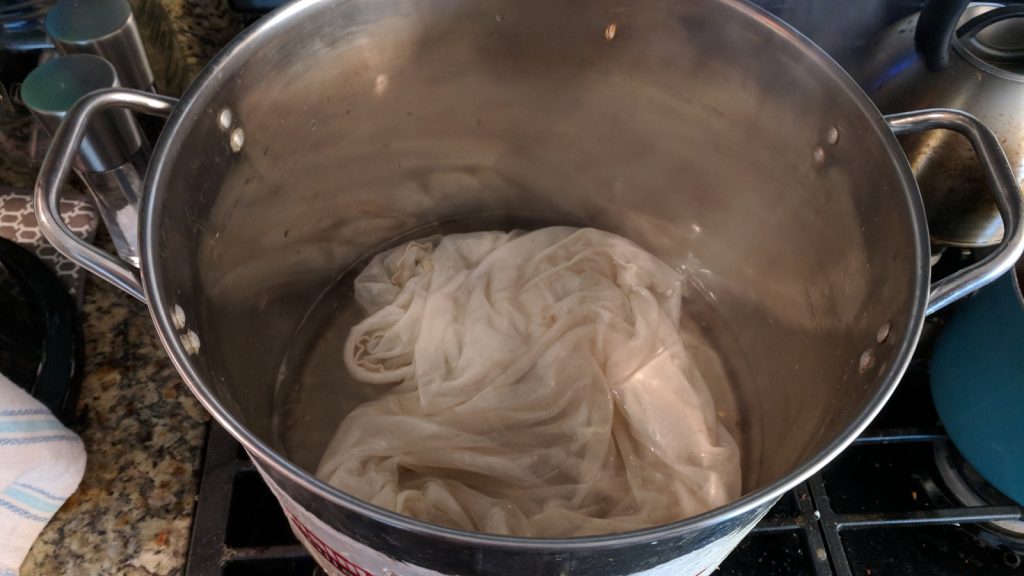

In between hop additions during the 60 minute boils, I prepared the fabric filter I’d be using to keep critters out of the open fermentation vessel by boiling it to reduce the risk of contamination.

Once each boil was complete, I transferred the wort through my counterflow chiller directly into sanitized fermentation kegs.

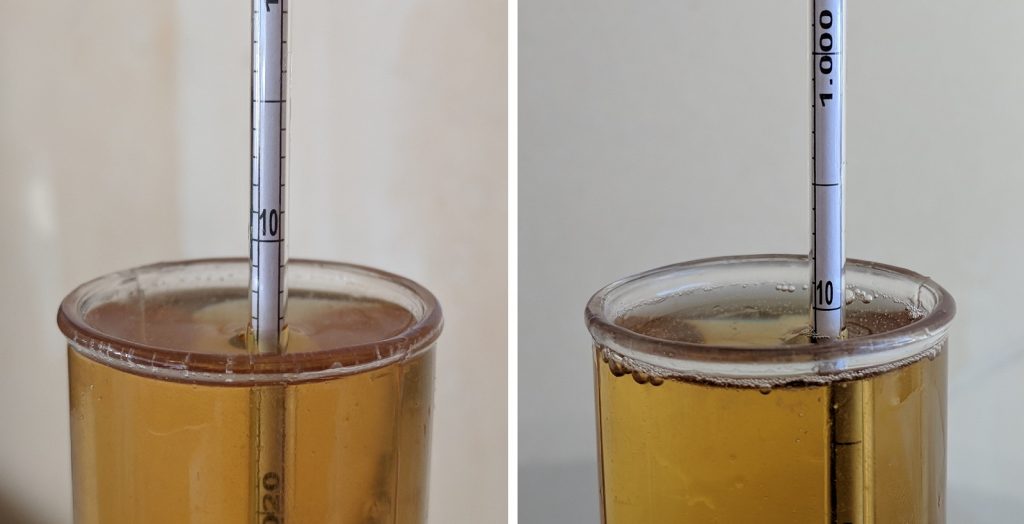

Hydrometer measurements showed that both batches reached the same OG.

After placing the filled fermentors next to each other in my chamber, I sealed both and let them cool to my desired pitching temperature of 64°F/18°C. This took about 2 hours, after which I evenly split the yeast starter between the batches and set the controller to my desired fermentation temperature of 68˚F/20˚C. One vessel was sealed as usual with the keg lid and blow-off tube attached to the gas post, while I simply placed the fabric filter over the opening of the other fermentation vessel.

The next morning, active bubbling was observed in the blow-off vessel for the sealed batch and a quick peek under the cover revealed the open fermentation beer had developed a solid kräusen.

Activity in both batches had subsided after 5 days, so I sealed up the open fermentation batch and attached a blow-off tube to reduce the risk of oxidation. After another 2 days, I took hydrometer measurements showing the open fermentation beer had a slightly lower FG than its closed fermentation counterpart.

While the surface of the closed fermenation beer looked normal, the open fermentation beer had what I only hoped were large yeast rafts floating on the surface.

Gelatin fining was added to each beer before I sealed them up, purged the headspace several times with CO2, and put them back in my cool chamber to cold crash. A few days later, I racked the beers under pressure to sanitized serving kegs then placed them in my kegerator and burst carbonated overnight before reducing the gas to serving pressure. I allowed the beers to condition for a week before serving them to participants.

| RESULTS |

A total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples of the closed fermentation beer and 1 sample of the open fermentation beer in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 13 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, which is exactly the number that did (p=0.03), indicating participants in this xBmt were able to reliably distinguish an open fermented British Golden Ale from one fermented in a closed vessel.

The 13 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 7 reported preferring the open fermentation beer, 3 liked the closed fermentation beer more, 1 reported having no preference despite noticing a difference, and 2 tasters perceived no difference between the beers.

My Impressions: The difference between these beers wasn’t as stark as I thought it would be, but out of 5 semi-blind triangle tests, I was able to identify the unique sample 4 times. I enjoyed these beers and perceived both has having a fairly mild malt character with a classic Cascade hop profile, though I noticed what seemed to be slightly less bitterness in the closed fermentation batch. Different enough to tell apart when focusing, but again, not nearly as much as I expected.

| DISCUSSION |

Open fermentation is a method believed by some to lead greater expression of esters, hence the reason some choose to rely on this approach for notably ester-forward beers such as British ale and even Bavarian Hefeweizen. Given results from a prior xBmt comparing Saisons fermented with the Dupont strain in either closed or open vessels, I didn’t personally think the beers in this xBmt would be noticeably different, but of course, I was wrong. The fact participants were able to reliably distinguish a British Golden Ale fermented in a typical closed vessel from one fermented in an open vessel suggests something about open fermentation has an impact.

One concern I had about the open fermentation beer was contamination– even though it was covered with a fine mesh bag, it seemed plausible something could get in there and have its way with the beer. While it’s possible this is what led to the significant result, I tasted these beers many times and never once detected any signs of contamination. Added to the data showing a majority of participants who were right on the triangle test endorsed the open ferment beer as their most preferred, it seems the more plausible culprits are likely differences in pressure or exposure to oxygen.

Not only were the beers unique enough for tasters to tell apart, but the method of open fermentation also had the more objective effect of encouraging greater attenuation. In talking with people after completing the triangle test, many noted the same thing I experienced in regards to the open fermentation beer being slightly more bitter than the closed fermentation beer, which perhaps the lower FG of the open fermentation beer contributed to.

This being just one point of data, I remain curious to explore the way open fermentation can shape the character of a beer, particularly with other yeast strains and beer styles. While I won’t be adopting open fermentation as my go-to approach, the significant results of this xBmt suggest it may very well be a valuable method for brewers looking to impart certain unique characteristics to their beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

42 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Impact Open Fermentation Has On A British Golden Ale”

Hang on. For significance, you required 13 correct selections, but two of those 13 said afterwards that they couldn’t perceive any differences. So they just guessed and got lucky? 11 accurate selections would not be significant.

I don’t have a horse in this race – I’ve used both open and closed fermentation – but before we start analysing the result we need to be clear about whether the methodology hangs together.

That’s the usual protocol; basically, the methodology also accounts for chance, and measure how likely random chance wasn’t the reason for picking correctly.

Intuitively that doesn’t make sense.

If the tasters who genuinely couldn’t tell a difference randomly guessed, they’d have a 33% chance of getting it right. So it seems reasonable to suggest that the 2 out of 24 tasters who were “correct” on the test had just made a lucky guess?

Micha is correct here, the way the p-value is calculated accounts for individuals who are correct via random chance. You can read more about this here!

You’ve chosen a method designed to reduce the likelihood of random chance, but you’re ignoring the two tasters actually telling you they couldn’t tell a difference – i.e. random chance.

The problem isn’t the triangle test, but the interpretation of the data.

That’s part of the issue, that it’s an interpretation. We could say they “couldn’t tell a difference”, but self-reported preference data is unreliable. We have absolutely no way of knowing if they guessed or not, even if they say they’ve guessed, they selected the correct sample and that can be a result of a perception they either can’t put words to, or can’t consciously recognize.

I understand your point, but the argument is better suited to a desire for an increased sample size. Anecdotal preference reports are not useful information in the interpretation of the p-value result.

This makes me happy. 🙂

If you repeat it, consider that the ferm chamber fills with CO2. If you can ferment more open — I do it in a 7.9 gal bucket to get more surface area, in a thin nylon kid’s play tent to allow gases to escape but kee dust away — you may see more of a difference.

BTW: “With claims that traditional English ales were fermented in open vessels, I went with a classic British Golden Ale recipe for this xBmt” -/ many traditional ales still ARE fermented open. And British Golden Ale is a very recent invention that doesn’t necessarily come from a tradition of open ferment. You’ll notice more esters in a traditional open ferment yeast too, like Wyeast 1469. The Fuller’s strain has a somewhat interesting and different environment in which it was domesticated (dropping system) than memel oak squares for example. Not sure what Imperial has in terms of open ferment yeasts.

1. Really interesting idea, I’ll definitely consider that when I repeat this (I plan to, maybe a hefe?). Tough part would be controlling temps, might need to make a water-based temperature control for something like that, to keep it out of a chamber.

2. I’ll definitely look into those additional yeasts as well. As always, this is a single trial with a specific process and yeast strain. Totally sound that with different equipment, or a different yeast strain, there may be more (or less) of a difference between the beers.

+1 on the golden ale thing. If you put the Manchester tradition of Boddington’s etc to one side, the first golden ale is generally reckoned to be Exmoor Gold, which was created in 1986 – as a style it’s younger than Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, and very much a product of the cylindroconical generation.

Yep, it’s true that Sam’s is somewhat less revered on this side of the pond, at least on the beer front as here breweries tend to be judged more on their cask offering, which in Sam’s case is definitely on the cheap and cheerful side. And they are perhaps taken for granted, but they do have some wonderful pubs. I think their prominence in BJCP is as much to do with distribution in the US as anything, but their bottles are better than their draught.

+1 too for the idea of using a proper open-fermentation yeast, the whole point of things like Yorkshire squares is that they are a way to look after the very specific demands of a specific kind of yeast, you can’t really split the two. It’s yeast that needs regular rousing, and is a proper top-cropper so the wort is protected from oxygen by a thick cap of yeast. So you definitely want to look at the likes of WLP037 and 1469, the latter is allegedly derived from the yeast you see in this video, being carried around in open buckets with not a HEPA filter in sight…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=622&v=4Cak4stt9v4

Black Sheep are another famous user of (round) squares, which they got along with their yeast from Hardy & Hanson – the yeast is kinda nuts in how top-croppy it is, it’s available from Brewlab as HH. Harvey’s are another prominent user of squares, their yeast came from John Smith’s.

So if you do this again, definitely use HH, 1469 or WLP037 and make a trad Yorkshire best. I wouldn’t sweat the temperature control too much, it’s pretty typical for British brewers to pitch cool and allow the wort to free rise, a bit of temperature fluctuation is good for esters in any case. As long as both arms of the experiment get the same treatment, just leave it in a bedroom or somewhere for the main period of fermentation, then cool it at FG for conditioning at cellar temperature.

The p=.03 is saying that if everyone just guessed you would see 13 people out of 24 get the correct answer 3% of the time by chance. So it is possible that the significant result is meaningless. It’s up to you decide if that is a rare enough event to say there is evidence that people can tell the beers apart.

I agree that lucky guesses should not count as significant.

But that’s now how statistics works. Statistical equations necessarily account for “lucky guesses,” hence our ability to say participant performance was no better than “random chance” when significance wasn’t reached.

Lovely account! Say, how was the closed fermentation batch oxygenated before fermentation? If the abondent supply of oxygen is the culprit here, maybe hitting the closed batch with a proper serving of O₂ will lessen the differences.

Nice experiment, if only to send shivers down the spines of the LODO community.

Not at all! Open fermentation occurs post-pitch, and the vessel is sealed right before fermentation is over in order to purge any remaining oxygen from the fermentation vessel.

The main advantage of open fermentation isn’t so much to encourage esters as to allow sluggish yeasts (including some British varieties) to ferment out without stalling. Allowing some oxygen in means they won’t run out of ergosterol if the wort hadn’t been oxygenated or the pitch rate was on the low side. It hadn’t occurred to me that fermenting open might also improve flavour but it’s interesting to see an effect. Most British homebrewers (me included) don’t really ferment open but we do use clip-on lids on plastic buckets rather than airlocked carboys, so some gas exchange does take place (and bugs/dust are kept out).

Also interesting to note that Pilsner Urquell, the archetypal lager, is fermented open. I think the fear of oxygen at this stage of the brewing process is overdone.

This is great information, thanks!

I’m not ready to make the claim “open ferm improves flavor”, for sure, but I’m looking forward to exploring this more.

Hi Ben, I don’t understand why you’d get more gas exchange in a fermentor capped with a clip-on lid than in a carboy with an airlock. Both scenarios allow excess pressure to escape the fermentor, while making oxygen ingress unlikely due to the positive pressure produced during fermentation. Please explain!

You said the difference in the two beers was bitterness. So no extra ester profile? Anecdotally I’ve had the same experience with San Francisco lager yeast. I’ve done closed and open fermentation side by side trying to nail the same ester profile as Anchor Steam without any luck. I tried cooler and warmer fermentation with both open and closed, and that didn’t help either. I have a feeling it might be something like surface to air contact (larger shallower fermenter with open fermentation) that might be the trick but haven’t tried it yet.

I agree, I think a look at a more shallow fermentation vessel may be really interesting for this variable.

In this beer, I got the difference on bitterness, which stands out as odd to me.

Ooooo! Shallow storage bin as an open fermentor?

I read something similar about German Hefeweizen yeast strains doing better in wider shorter fermentors as well (fermentor geometry). They also have been touted to do better with open fermentation. I’m sure there is probably something to your theory. I am planning on open fermenting my next Hefe to see what effect it might have on flavor.

Impressive work doing your side by side comparisons! After doing only one myself, I can see how valuable it is to compare small or even large variables.

Another great exbeeriment. I’ve always been too scared to try this myself, due to fear of contamination. I suppose this was at least partially accounted for by the mesh bag, and the fermentation taking place in a sealed chamber, as opposed to an open environment like a room or garage.

That said, unless the fermentation chamber is kept quite clean (from random beer spills, blowoff driplets, etc) various yeasts from previous batches and bacteria are surely present in there as well. Good thing they can’t climb?

Either way, I was very interested in this article, and happy to see one that I expected to achieve significance actually do so for once!

I’d love to see this done with a NEIPA.

There are definitely other yeast and bacteria in that chamber. New Glarus has large open fermenters for wheat beers and I remember the room bring HEPA filtered and sealed off.

A fridge is one of the worst places in terms of bacteria and yeast.

These are likely different because some wild yeast got in the open batch.

Absolutely a possibility here. I bleached the hell out of the chamber before hand, but that’s obviously imperfect and also the seal on a fermentation fridge (in addition to me opening it up several times) isn’t perfect either.

No sign of infection as far as I can tell (this beer is heading to comps soon!) but I wouldn’t rule it out necessarily.

Wadworth is a British brewery that allows public tours and you walking meters away from the huge open primary fermentors.

“In fact, the revered Samuel Smith’s Brewery still use the Yorkshire Square to ferment in, a unique vessel that leaves the fermenting beer exposed to the environmental air.”

I live 2 minutes from the Sam Smiths brewery. ‘revered’ is certainly not a word that it is used to describe it in England!

Ha! You know, off the top of my head, I don’t think I had a single Samuel Smith beer during my stint in England!

The BJCP lists quite a few of their beers as classic representations of style.

Based on the results of a number of exBEERiments I ditched my dedicated fermentation vessel a while ago and just ferment in my boiling kettle with the lid on. I haven’t noticed any change in the quality of my beer and it means less racking and less stuff to clean, sanitize and store.

I actually know of a few folks who do this regularly with similarly positive results.

I’ve got an open fermentation going on in my boiling kettle right now. I like that I have one less vessel to worry about. Though honestly it only saved a couple of minutes.

I do this quite regularly with my Hefe’s. I wish I could find the video clip I watched from a German brewery. Long story short, open fermentation and they cooled the wort by letting it trickle over some pipes next to a window.

One point: Geometry of the fermentor. Your biggest bang will come from large, shallow, rectangular fementors.

One way to factor out random guessing in the statistical analysis would be to use a more stringent measure of statistical significance (I’ve posted this link in comments on earlier exbeeriments: https://psyarxiv.com/mky9j). This would mean fewer significant exbeeriments.

My understanding is that standard operating procedure for open fermentation is to transfer from primary to secondary once the krausen falls to avoid oxidation, though this ends up removing the beer from the yeast cake. I’d be interested to see a version where both the closed and open fermented beers are transferred when they get close to final gravity, so that the primary yeast has less of a chance to clean up fermentation byproducts.

The points about fermenter geometry are interesting in that most open fermenters are shallow while most closed ones aren’t. To pick apart the effects of open vs closed and shallow vs deep, one would need a bunch of exbeeriments. Keep that stuff coming!

FYI – Geary’s of Maine also uses open fermentation! DL also recirculates during fermentation.

Cadaver trays would be awesome for this type of experiment. New ones would be recommended though.

I work at a 8 bbl brewery and we have only open fermenters the other big advantage of these vessels is that we top crop the yeast and use it for 50 or so beers before we have to buy a new one great money saver

Great experiment first off! As said before that open fermentation in your closed fermentation chamber would only allow it to be open fermentation to that chamber. Maybe if you had it fully open to the room you are fermenting in it there may have been a larger significant difference. would be good for a 2nd round. I’m gonna have to give this a try and see what happens.

Those OG photographs show some issues with consistency between batches. If they don’t even look the same going into fermentation, how can they be quantitatively be compared based on a fermentation variable? Or you have weird shadows in your garage. This site is full of false data. If it gets people started on homebrewing, great, but the QA/QC of the “team” is questionable.

It’s not inconsistency, it’s lighting. We’ve never claimed to be expert photographers. Your presumptuous perspective of our QA/QC leads me to believe you have something less “questionable” to offer?

Nice xbmt guys! I love to follow your xbmts, and may I made a sugestion for a new one? I was wondering if brewing on BIAB or 3-vessel systems make the bitternes perception change. I notice that some of my beers – I have a 15L BIAB equipment -, even when I put the IBU range on the maximum limit of the style, doesn’t appear to have the perception of the real bitternes – wich is great in some styles, but bad in others -, so if you guys have some space on the schedule of the next xbmts, I would love to see that!

Thanks for the great tests and conclusions

Marshall I agree.