Author: Marshall Schott

About 3 years ago, I designed an American-style Red Ale with a simple grist, bittered to 30 BU with Magnum, and finished with a moderate amount of Centennial and Cascade. When it came time to brew this beer, I realized my Magnum stock was depleted and reached for the most similar AA% hops I had available, which happened to be Chinook (Shh-nook). Despite recently learning Chinook possessed relatively high cohumulone (CoH) levels, purported to produce a harsher bitterness, my skepticism prevailed and I tossed a charge in at 60 minutes. The finished beer was good, but I’ll be damned if I didn’t experience it has possessing an unpleasantly sharp bitterness.

I’m certainly no chemist and claim no expertise on the matter, hence my deference to those much smarter than me. In For The Love of Hops: The Practical Guide to Aroma, Bitterness and the Culture of Hops, Stan Hieronymus discusses how research in the 1950’s (Rigby et al.) suggesting higher CoH levels produce harsher bitterness drastically influenced the brewing world by increasing demand for low CoH varieties, which ultimately impacted research and breeding. However, as Stan points out, later studies performed by our friends at Oregon State University demonstrated experienced tasters were unable to distinguish between beers containing differing CoH levels to a significant degree. Some have gone as far as to conclude CoH’s erroneously bad reputation is leading to some not-so-positive repercussions given findings from newer studies.

I’m certainly no chemist and claim no expertise on the matter, hence my deference to those much smarter than me. In For The Love of Hops: The Practical Guide to Aroma, Bitterness and the Culture of Hops, Stan Hieronymus discusses how research in the 1950’s (Rigby et al.) suggesting higher CoH levels produce harsher bitterness drastically influenced the brewing world by increasing demand for low CoH varieties, which ultimately impacted research and breeding. However, as Stan points out, later studies performed by our friends at Oregon State University demonstrated experienced tasters were unable to distinguish between beers containing differing CoH levels to a significant degree. Some have gone as far as to conclude CoH’s erroneously bad reputation is leading to some not-so-positive repercussions given findings from newer studies.

And yet, many remain concerned. Whether in the form of anecdote like my own or advice given by industry authorities, the belief that higher CoH hops produce harsher bitterness persists. As does my curiosity.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between 2 beers of the same exact recipe bittered to the same expected level (IBU) using hops of similar AA% with either high levels of CoH or low levels of CoH.

| METHOD |

DISCLAIMER: Designing an xBmt isolating only CoH levels posed a bit of an issue– without securing pure CoH, which I couldn’t find anyway, there really was no good way of going about it that didn’t involve introducing some other variable. When testing stuff like this on the homebrew scale where access to certain shit is limited, we’re forced to make some concessions, which isn’t scientifically ideal though can still produce results applicable to the typical homebrewer. In this particular case, such a concession had to be made and I opted to compare two hop varieties similar in AA% and oil content while differing quite drastically in CoH levels. Despite efforts to reduce as much flavor and aroma impact as possible, it’s true any differences could be a function of hop characteristics other than CoH. I fully get this and have no intention of misleading anyone– if you’re concerned, view this xBmt not as a comparison of CoH levels but different bittering hops. Moving on…

I consulted with more folks than usual when designing this xBmt, all who offered great feedback. One of these people was John Palmer who suggested I replace the ESB I was planning to brew with something lighter and cleaner with a single bittering hop addition. So, I dropped the specialty malts and all but a lonely 60 minute hop charge. Exciting, eh?

British Golden Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 40.0 IBUs | 5.5 SRM | 1.054 | 1.014 | 5.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.054 | 1.014 | 5.3 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, Maris Otter | 10 lbs | 90.91 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 15L | 1 lbs | 9.09 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simcoe (13.8%) | Chinook (14%) | 20 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.8 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Ale III (1318) | Wyeast Labs | 73% | 64°F - 74°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Unimpressed after my first use of Wyeast 1318 London Ale III, I figured I’d give it another go and built up a start a couple days before brewing.

The evening before my planned batch sparge brew day, I collected both volumes of liquor and milled the grain while making sure my kids didn’t get run over.

Early the following morning, my tiny bottom’d assistant accompanied me to the garage where the first order of business was heating the strike water.

To reduce the introduction of extraneous variables, I opted to perform a single mash and hit my target temperature dead on.

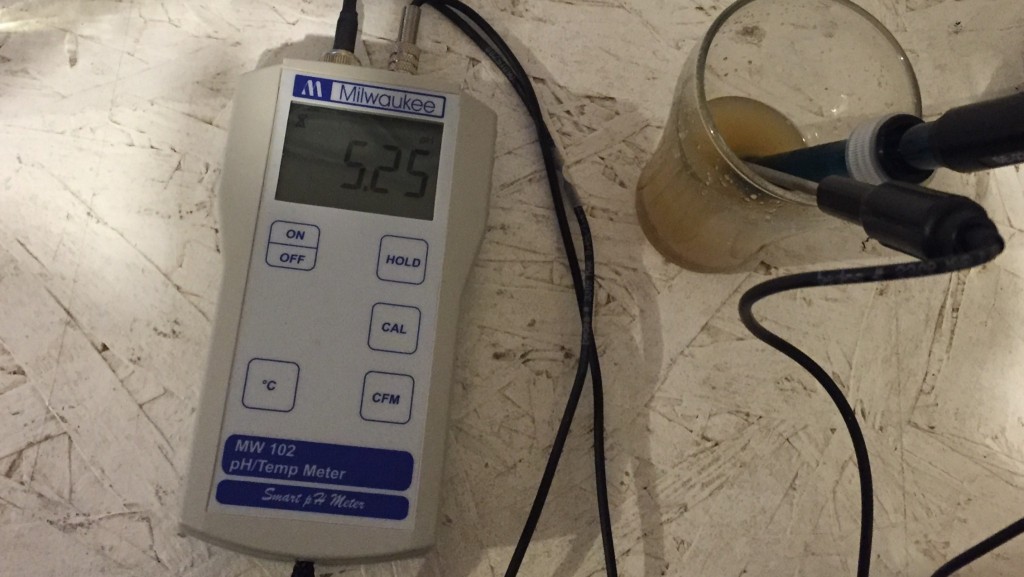

About 10 minutes in, I pulled a small sample to confirm the mash pH was where I wanted it.

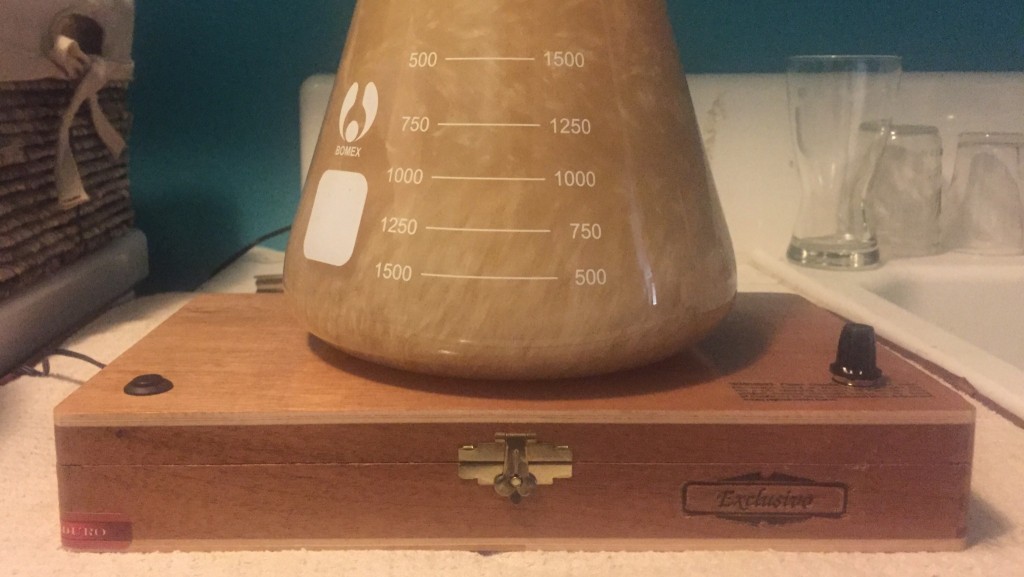

Once the mash was complete, I collected both runnings or sweet wort in a single kettle, gently stirred until well homogenized, then transferred an equal portion to a second kettle. To allow for consecutive chilling, I staggered the boil step by 15 minutes.

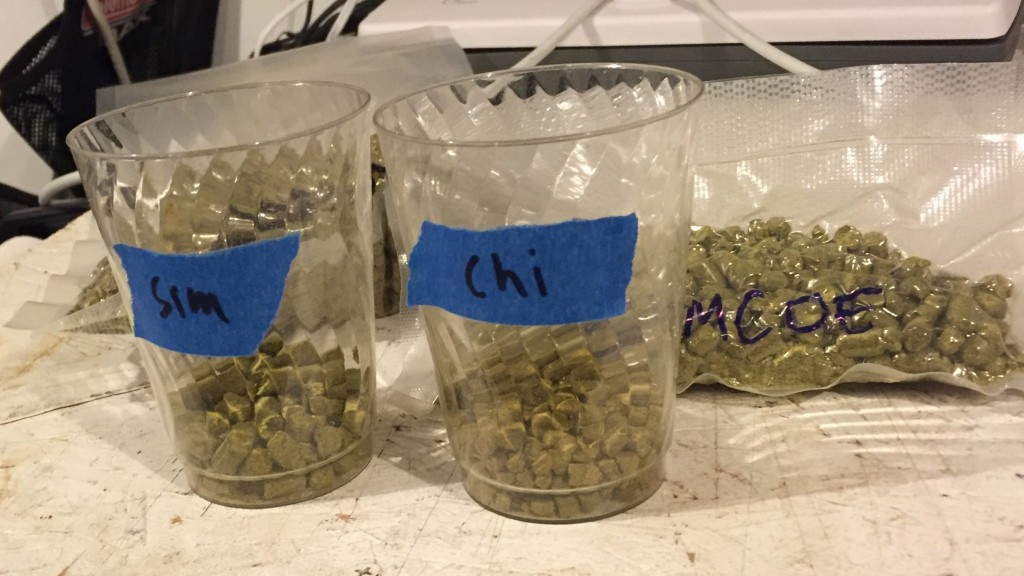

As the first batch was coming up to a boil, I measured out the single bittering addition of hops that would be tossed into either batch, it differed by literally 2 pellets given the closeness in AA% between them.

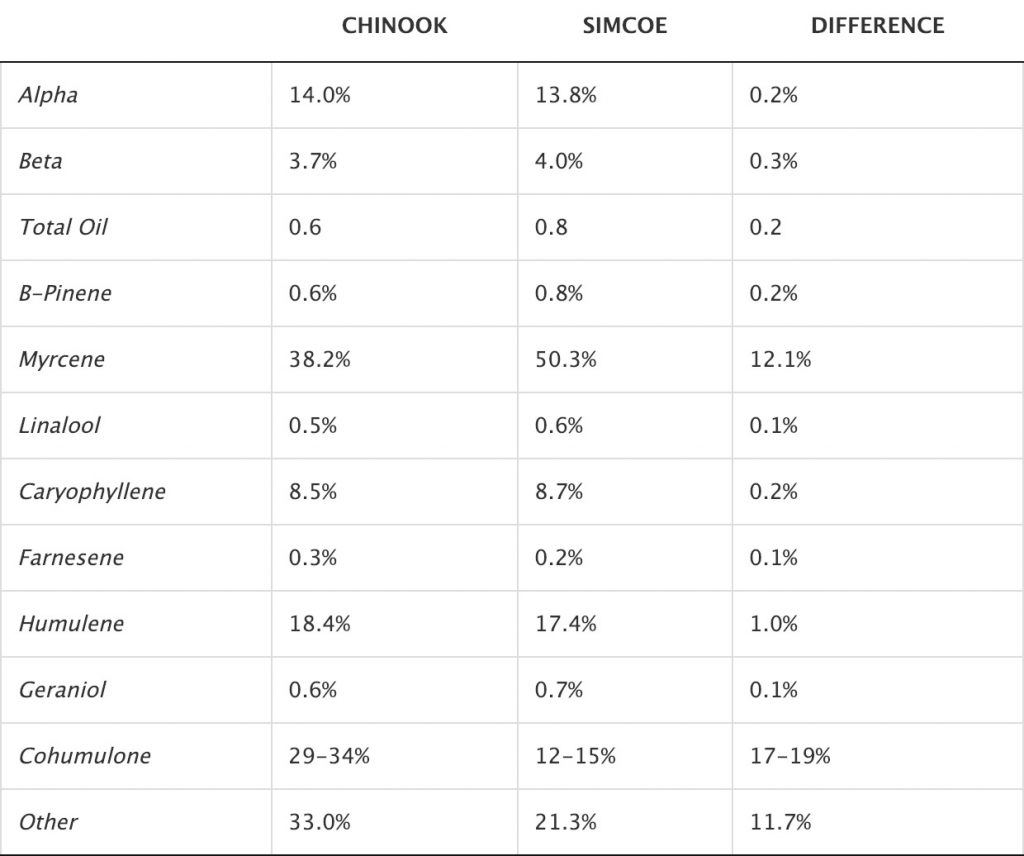

My decision to use Chinook and Simcoe came not without research and consultation. In fact, I wasn’t even aware Simcoe was a low CoH variety until I started designing this xBmt. My primary goal was to compare two hops with drastically different CoH levels, though I secondarily wanted to them to be similar in as many other respects as possible. My first stop on this quest was the USA Hops Variety Manual, which is where I discovered Chinook and Simcoe were at either end of the CoH spectrum. With the help of my friend Matt Chrispen from the Accidentalis blog, and utilizing Scott Janish’s awesome Hop Oils Calculator, we determined that Chinook and Simcoe share many similarities, the exceptions being CoH (woo!) and myrcene (boo!).

Myrcene is known for imparting a “green” character that’s sometimes described as mangoe-like, earthy, and to some, reminiscent of it’s danky cousin (it’s the most common terpene in weed). It’s also highly volatile, particularly in warmer environments, meaning it dissipates rapidly when used pretty much anywhere other than the dry hop. While less than ideal, Chinook and Simcoe seemed the best fit for an xBmt of this nature. To be clear, both were from the 2014 harvest season.

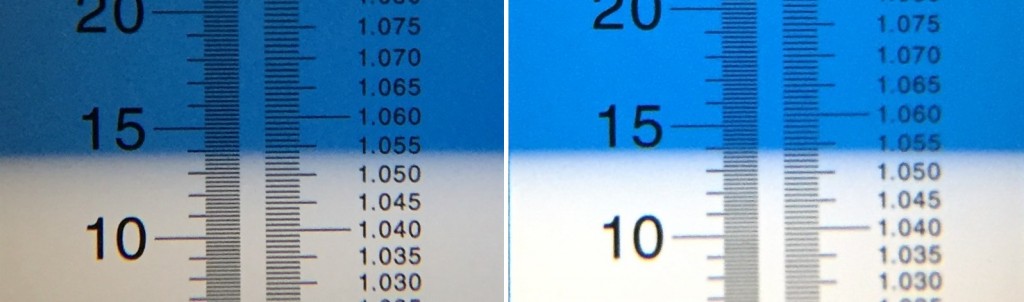

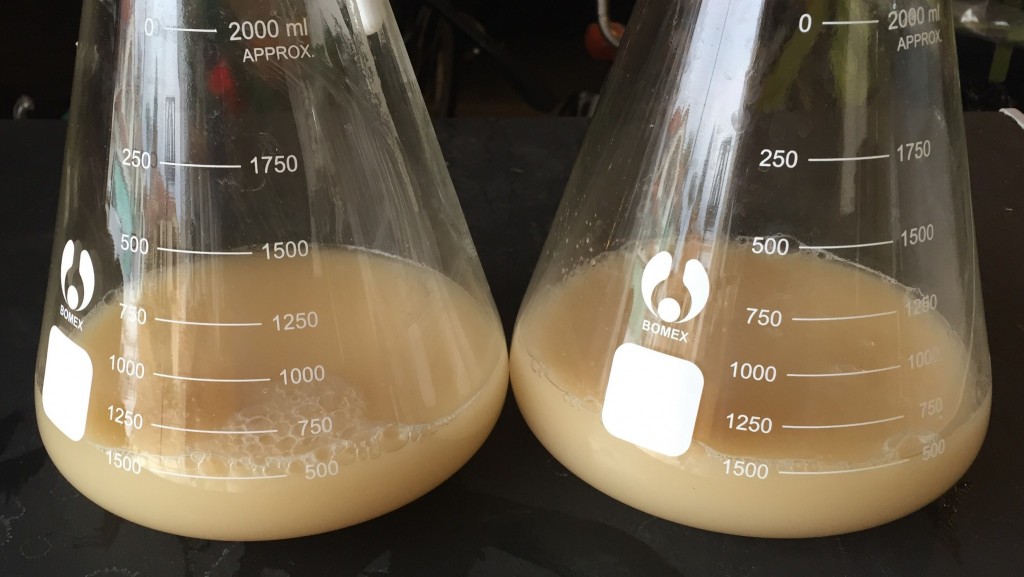

Each boil proceeded as normal, the first finishing 15 minutes before the second, and both were quickly chilled to my target fermentation temperature of 66°F/19°C. A refractometer measurement of both worts at this point revealed my process was consistent between the batches.

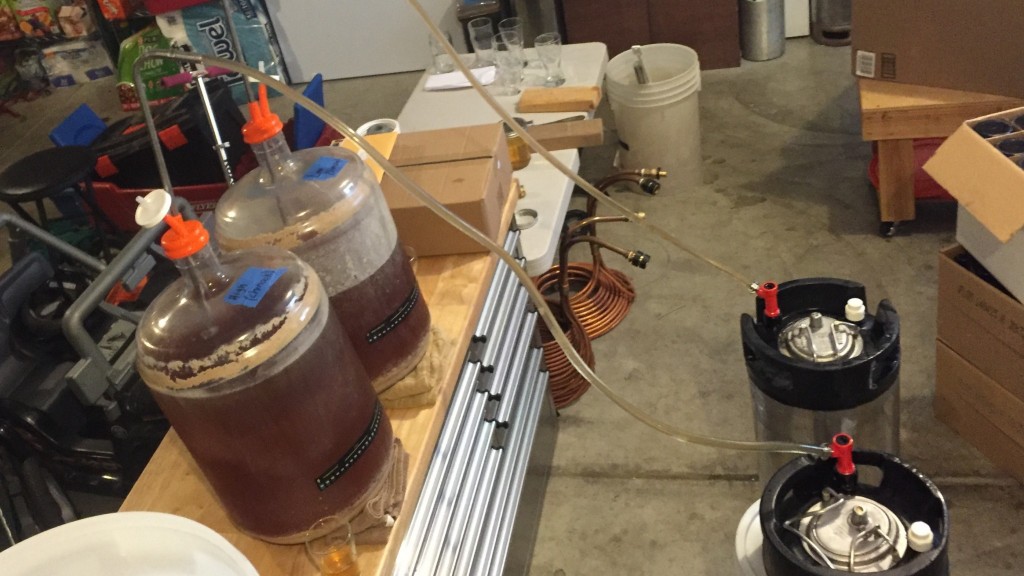

I proceeded to transfer the wort to separate 6 gallon PET carboys that were placed in my temperature controlled fermentation chamber.

The single large yeast starter was then split evenly between two clean and sanitized flasks.

Each carboy was hit with 500 mL of viable yeast slurry with signs of active fermentation showing up just 8 hours later.

Fermentation appeared the same between the batches the entire time. I began ramping the temperature to 72°F/22°C after 4 days of fermentation and at 10 days post-pitch both were seemingly done, which two hydrometer measurements taken 3 days apart supported.

Following a 2 day cold crash and fining with gelatin, I transferred the beers to kegs.

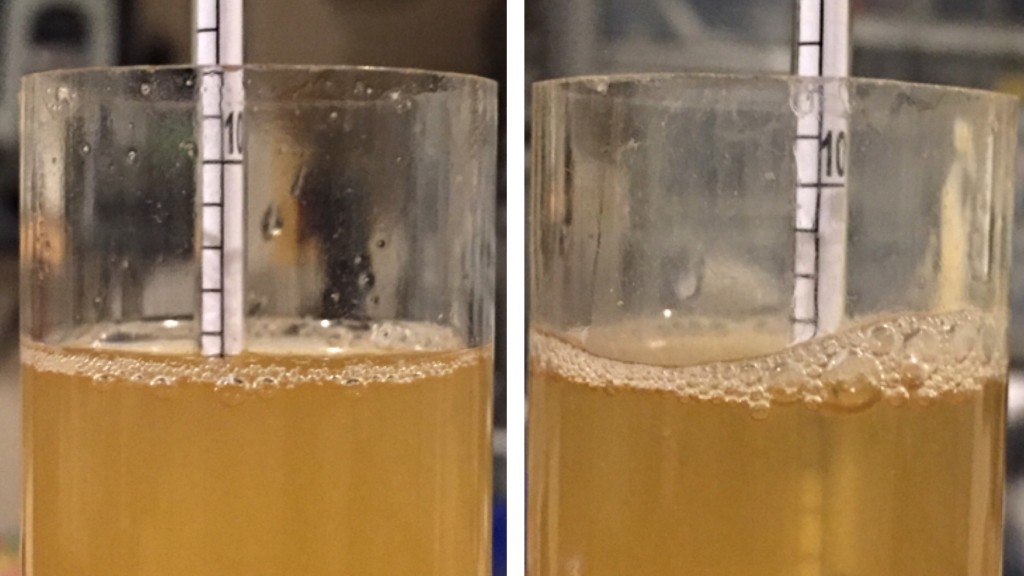

After about a week of conditioning on gas, the beers were carbonated and ready to serve! The clarity difference was rather interesting to me and remained the entire 3 weeks these beers were on tap.

| RESULTS |

A total of 23 people contributed data to this xBmt including numerous BJCP judges, experienced homebrewers, craft beer enthusiasts, and my neighbor. Each taster was blindly served 1 sample of the Simcoe/low CoH beer and 2 samples of the Chinook/CoH beer in opaque cups then asked to identify the one that was different. At this sample size, 12 accurate selections (p<0.05) would be required to imply statistical significance, and in the end exactly 12 (p=0.048) identified the unique sample, suggesting participants were able to reliably distinguish between a beer bittered with high CoH Chinook from the same beer bittered with low CoH Simcoe.

A brief comparative evaluation of only the two different beers was then completed by the 12 tasters who were correct on the triangle test. Regarding preference, five tasters chose the Chinook/high CoH beer and five selected the Simcoe/low CoH beer, the remaining two indicating they preferred neither over the other. Even more evidence to support the notion that preference is a subjective matter. The variable being investigated was then revealed to these participants and a brief explanation regarding the purported impact of CoH on bitterness perception was provided. Still blind to which beer was in which cup, tasters were instructed to select the one they believed was made with the Simcoe/low CoH hop, which resulted in seven correct and five incorrect selections.

In follow-up discussions following completion of the survey, a point at which tasters were aware of the nature of the xBmt yet still unaware of their performance, the most commonly cited factor contributing to their ability to distinguish the beers was, you guessed it, the perceived bitterness.

LAB ANALYSIS

While collecting data for this xBmt, I was contacted by Dana Garves, founder of Oregon Brew Lab, which offers brewers all sorts of rad and affordable options for beer analysis. She kindly volunteered to run lab tests for xBmts that might benefit from more objective measures. While I didn’t expect there to be much of a difference in IBU, I thought it’d be interesting to have this data available, as similar bitterness levels would provide even more support for CoH as being the most likely contributing factor to the perceived differences. Unfortunately, I impatiently packaged and shipped off samples without reading through the instructions Dana sent me, which led to the accidental combining of the Chinook/high CoH and Simcoe/low CoH samples prior to being analyzed. Fuck. Regardless, I found the results of the test rather interesting, as it showed the combined sample was at a measured 29 IBU, 11 shy of the level predicted by BeerSmith using the Tinseth calculation for both batches. Did one sample pull the other down or was the predicted IBU that far off for both? Hmm.

My Impressions: First off, my bias– I was wholly convinced these beers would be indistinguishable based not only on stuff I’ve read and heard from trusted sources, but personal experiences following my presumption formed after the Red Ale story I told above. Man, was I wrong. In all of my 5 attempts, which I completed on different days with different people serving me and various levels of inebriation, I got it right. And I mean it when I say they smelled and tasted exactly the same, the only difference I picked up was in the harshness of the bitterness. Go fucking figure. I feel like a schmuck even saying it. While pretty subtle, I found the Simcoe/low CoH beer to be characterized by a smoothness from start to finish while the Chinook/high CoH beer had more of a sharp, snappy bitter character that lingered on my palate a bit longer. It wasn’t a crazy difference, but I have no problems classifying it as noticeable.

As if that wasn’t enough, when comparing them in a “blind” side-by-side, I consistently preferred the Chinook/high CoH beer! For years, I’ve been using hops said to impart a smooth bitterness, chasing the preferences of those whose opinions I read and listened to, all the while ignoring my own desires.

| DISCUSSION |

I’ve no doubt these results will be used by some to confirm CoH levels do in fact impact the harshness of bitterness, while others will point to the “obvious fact” the differences were due the use of different hop varieties, and still some will write the xBmt off completely when they notice a p-value of 0.048 isn’t “very significant.” To be honest, I find myself waffling between all of these…

The statistics indicate a distinguishable difference… but the hops were different… but they were also really similar in so many respects… but if only 1 person’s guess was wrong instead of right… but p-values suck… but… but… but…

Ultimately, I’m left to make a decision based neither solely on the data nor my personal experience, but on a combination of both. I was able to tell a difference beyond that which might be expected if I were randomly guessing, and from this I developed a preference for the beer made with the Chinook/high CoH hop. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to recommend others adopt my perspective, what good would that do other than contribute to growth of my ego? Rather, I encourage anyone interested in this stuff to mess around with it in their own brewing, it’s a fun and relatively risk-free way to learn something new on an experiential level, which I view as being of utmost value. This xBmt certainly forced me to rethink things and you better believe it was only the first of many focusing on the impact bittering hops have on beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Brülosophy Merch Available Now!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

45 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Bittering Hops: High vs. Low Cohumulone In A British Golden Ale”

It is a well known but perhaps not well spread fact that IBU calculators consistently overestimate. One factor is that the formulas typically are calibrated for professional brewing systems with better utilization. And perhaps even more important is that the estimated IBU is for the wort, not the fermented beer. Typically at least 20 % of the bitterness is reduced during fermentation.

Every beer I’ve had analyzed has been within an IBU or 2 of what Promash predicted. I think you’re over generalizing

.

No I am not. The IBU reduction during fermentation is well known, and clearly noticeable if you taste the bitter wort and compare with the final beer. The wort is always much more bitter.The Tinseth formula is calibrated for wort, you can mail him and check for yourself if you don’t belive me. Of course it is possible to adjust the parameters in the Tinseth so that you at least get a correct estimate on average. But you will still have large deviations and if you get within 5 IBU you should be happy.

Moreover, it looks as if the the hops storage index (HSi) wasn’t taken into account in regards to the predicted IBU. Even if the hops were vacuum stored in the freezer, it seems unlikely they were still around 14 % a/a, considering these are from the 2014 crop. I have not had my homebrews tested, but I always use Promash to estimate the IBU loss due to storage temp and time as I feel the predicted IBU is more accurate. I don’t have Promash handy, but I would’t be surprised if the hops had lost 1/4 or 1/3 their initial bittering potential. Maybe it explains part of the IBU prectidec VS tested discrepancy? Correct me if I’m wrong Marshall, unless 13,8 and 14 were the adjusted alpha?

Those were the percentages listed on the hop bags. However, given they were both from the 2014 crop, I’d imagine any degradation was close to equal between them. I’m more inclined to believe, at this point, that CoH actually imparts bitterness beyond that expected from AA% alone.

My one time using Brewer’s Gold to bitter with, it was as you described Chinook. Sharp bitterness that lingered.

I did something similar after getting a harsh batch a few years back. I used Glacier to bitter ( although a low AA% ) because it seems to be the absolute lowest Co-H hop out there. The beer I made was good but then I brewed it again and used Magnum in place of Glacier ( Based on what others said about Magnum ) which to me ended up being smoother and more enjoyable than the Glacier bittered beer. That totally goes against what this Exbeeriment has to say because Magnum Co-H is WAY higher than Glacier. I wonder what other contributors there could be to this bittering exbeeriment ? I have always thought the cleaner tasting bitterness comes from higher AA% hops and maybe that is because it imparts way less oil into the beer than a low CO-H hop would that is a lower AA% ? >>> Perfect example is Glacier [AA% 5 AND Co-H 13% Vs Magnum AA% 15 AND Co-H 29% ] Any thoughts on this being another monkey thrown into the lake ?

This is a classic issue separate from CoH levels; you will get more secondary (and sometimes unwanted) hop flavors from using a ton of low acid hops than using a small amount of high acid hops.

This is a bit of a tangent, but I’m making a beer next week that calls for 1oz of cascade @ 60 mins for bittering, well I’m cheap and don’t have enough cascade so wanted to substitute it with 1/2 oz of chinook.

Cascade: 6% AA, 36% cohumulone, 12% humulene

Chinook: 12% AA, 32% cohumulone, 22% humulene

I think that 1/2 oz chinook would give roughly same AA%, same humulene, but HALF as much cohumulone. Am I thinking about this the right way? Would it be a reasonable substitution? Thanks!

I wouldn’t have a problem with that substitution, but that’s just me.

Brewed a Simcoe Pale Ale this last weekend. Very excited!

Really interesting. I would love to read about the participant’s perception on taste and aroma, and how they described it. Did you not take a survey this time?

Matt

After initially allowing participants to provide subjective feedback and noticing no patterns, we dropped that piece from the survey. In the event a particular variable proves significant over multiple trials, we’ll approach testing it from a different perspective. Perhaps CoH will be one these variables!

I have a question for you guys. Did you all ever consider including an option for a tester to choose “I don’t know” or “i can’t tell the difference?” It seems to me that this would reduce some of the randomness out of the results. I have no idea if this is a viable option but I have been curious since the first day I happened upon your awesome site.

The whole purpose of a triangle test is to evaluate distinguishability, meaning in order to get meaningful information, people have to choose the one they think is different. The idea is that since 1 is definitely different, at least on some level, then to say the variable matters, people have to choose the odd one out. “I don’t know” participants would be expected to select randomly.

I think it’s a good point though. If they don’t know, but guess and get it right, why should that count as statistically meaningful?

That’s called “chance” and it’s accounted for in the statistical equation 🙂

Interesting! Random somewhat related tangent. I’ve made a similar recipe (I think back in 2013) to the one in this post (swap the Simcoe/Chinook for Cascade and swap the WY1318 London Ale III with WY1098 British Ale) and had a similar experience with hop character being different than expected. I was expecting grapefruit/citrus late hop character from the Cascade but instead it yielded something closer to Fuggles in character (I was originally aiming for blonde ale, but due to the Fuggle character I later called it a summer bitter). I thought it might just be me, but then brought it to homebrew group meeting and most people had the same response (I didn’t tell them upfront it was Cascade, just revealed it to them if asked).

Also, on a related note, it would be interesting to see this study repeated on an IPA-grade recipe, pushing IBUs to the 60+ range and using an American ale yeast. Since these hops are commonly used in IPA styles, tasters may be more calibrated toward their character in that setting. Anyway; very cool; cheers!

Very interesting results. I am definitely curious if you tested the same variable but did the single addition in both beers as a FWH. I use warrior hops for all my bittering but I very rarely do them as boil additions, with its higher-ish CoH is this variable reduced by the FWH process. I’ll even bitter my IPAs with a FWH addition of warrior but I never really get that typical IPA bitterness (calculated IBUs after all said and done around 90).

Would be really cool if it flipped the results one way or the other(further into significance or further away).

I recently brewed a single hop Galaxy Pacific Ale, clone of the Australian Stone & Wood beer, wheatbeer grist of 40% flaked wheat, pils malt etc, US05. All the clues to the actual recipe seemed to recommend using galaxy for bittering. The ones I used were 2015 Co-H 36%, AA 14%.

I too noticed a harshness to the bitterness, in this beer, showing up easily as it has such a light grist. I also mashed a bit lower than planned as had a power outage during the mash and my electric RIMS shut down.. so FG was 1005.

In any case the harshness is in the aftertaste, so a few seconds after you take a swig.. And it lingers on the palate, as you noted Marshall, with your red ale. Tastes great mind you, just a bit of a let down in the aftertaste. Just not the complete beer nirvana experience we are after.

That said, this harsh bitterness seems to be diminishing rapidly with bottle age. It was bottled 30th jan 2016, now two months later the effect is hardly noticeable.

For the commercial product, this may not matter, as the supply chain would on average add at least a few weeks to the age of bottles.

I wonder would ditching the 60 min and switching to a 20min addition or even 10 mins change this result for Galaxy? Might give that a go next time.

Just made that Evil Twin red ale recipe on the mrmalty website using this technique, where you add hops for the first time at 20mins to go. http://www.mrmalty.com/late_hopping.php

In fact that might be a good exbeeriment, two identical beers, one bittered at 60 mins and another at say 10mins, using same high AA hops but differing amounts, calculated to achieve the same IBU’s and the same amount of flavour and aroma

It’s so on the list!

Actually 10 mins is probably a bit too late, may be difficult to balance the two batches, probably 20 mins would be better. This red ale I just made with the 20min bittering addition, tasting the half fermented wort, appears to have an impressive whack of bitterness while still being impressively smooth. This might just be the heavy body I have in this beer, lots of crystal and mashed at 154.4F/68c, but the bitterness flavour did bring a smile to my face when I sampled it.

In the picture of the two carboys in the temperature controlled freezer, what are the black digital looking things that are next to the air locks?

That’s The Beer Bug, I’ve been testing it out for awhile in preparation for a product review. So far, I’ve enjoyed the convenience of being able to monitor fermentation from a distance, but it is pretty expensive: https://www.thebeerbug.com/?rf=54614726

Marshall, I’m curious if you know what your water profile is?

I do, you can see it in this article:

https://brulosophy.com/2014/09/18/a-pragmatic-approach-to-water-manipulation/

For this particular beer, I built it up to the Yellow Balanced profile in Bru’n Water.

I think this one is very interesting. I’ve seen British breweries blend different hops for the bittering addition, which might not be as silly as it sounds.

Does raise quite a few questions about designing the bittering charge (specially of less hoppy beers).

A potential confound as you can’t control cohumulone directly is whether you get the same result repeating the experiment with two different hops of the same alpha and the same cohumulone level. Potentially, some other flavour compounds could explain the difference in bitterness.

I also wondered if an experiment on low alpha vs high alpha bittering has been carried out. Kristen England has mentioned about getting flavour from bittering additions of EKG, which given these results is not as crazy as it sounds (even if what is left might not quite be what is commonly known as flavour). An xbmt comparing an oz of Magnum to 3oz of EKG for bittering is likely to be tasty.

I’ve actually made two guinness clones, same grist of ale malt, unmalted flaked barley and roasted unmalted barley. Used EKG 4%aa to bitter the first one, 71 grams or a bit over two oz, and for the second batch used about half (40 grams) of higher aa Challenger, think it was closer to 8%.

I am less impressed with the challenger hopped one, even go as far as to say slightly disappointed, and the bitterness seemed to be the difference, it was ‘not rounded’ or something. My recipe called for the EKG, and I had run out and figured the challenger should do. So there’s some anecdotal evidence.

Considering I really like bittering with Challenger you did get me hooked 😀

I’ve seen Kristen say that 3oz of 5% will age better than 1oz of 15%, due to the tannin content being mostly a function of the total hop amount. Tannins apparently last forever, which may explain their popularity in wine and oak-aged things. I use low-alpha hops for things I intend to age, but it’d be nice to know if I’m wasting my time and money.

Nice experiment. Re: storage index, etc: I’ve looked into the storage index equations. they seem to be based on a few studies evaluating effects of age and temperature on hops within a very limited range of storage conditions. for instance storing Hops at room temperature in a bale at the brewery for 6 months, etc. However I didn’t see any data points for hops stored in a deep freeze at minus 20 in a vacuum, for instance. I’m very skeptical about those equations.

Also, in one of the studies, alphas declined with age, but betas increased, and the perceived bitterness remained the same, IIRC. I suspect bitterness is derived from other components than just alpha acids

I have always perceived a harsher bitterness when I use Chinook. As a result I’ve started using it much later in the boil and just scaling the amount for 20 minutes rather than 60. In my experience this reduces that harshness. Maybe that’s your next EXBEERIMENT. : )

It is on the list!

In researching the same subject, I stumbled upon this pretty cool link:

http://www.homebrewersassociation.org/attachments/presentations/pdf/2014/Cohumulone%20Friend%20or%20Foe.pdf

The gist is that because iso-cohumulone is more soluble in finished beer than iso-humulone, given the exact same calculated IBUs, any beer brewed with high CoH hops will have a higher lab-read IBU content than a beer brewed with low CoH hops. This implies that there may be no qualitative difference in bitterness between the two substances, only a quantitative difference. The attached link suggests a possible CoH factor that can be applied to an IBU calculation to give a more accurate final IBU quantity in fermented beer.

I think an interesting possible xbeeriment would be to repeat the one you’ve just done, but adjust the amount of each hop based on this proposed CoH factor. The attached article gives details for calculating such a factor.

Cheers,

Phil

A fantastic article/presentation, indeed! I was pointed to it by Mike after publishing the xBmt article, it’d be fantastic if IBU calcs were able to account for CoH levels. Cheers!

While for any particular high co-humulone hop to have some harsh character may be possible, Tom Shellhammer clearly demonstrated that it isn’t the co-humulone that leads to that perceived harsher bitterness and even suggests that higher cohumulone levels may be perceived as less harsh than isohumulone. This was using the purified acids in a light lager and in unhopped ale.

Very nice article. My problem is that all my IPAs start out having a good hop flavor for the first 3 weeks after bottling/conditioning but then turn incredibly bitter with no hop flavor after two months or so. I read this article thinking that the cohumolone theory might be culprit. Now I’m not sure. Any suggestions on what might be the cause?

Many believe hop drop off is a function of age, hence the reason it’s so often recommend to drink IPA as fresh as possible.

I don’t know if CoH is everything though. My bittering hop of choice is summit. Doesn’t matter the beer. Kolsch, IPA, Belgian tripel, I’ll always use summit for bittering. Summit has the same CoH, or even slightly higher than chinook, but I’ve always found the bitterness cleaner. Prominent, but without the harshness I got anytime I used chinook. And since I enjoy using summits as a complimentary hop ala CTZ, I buy it in bulk instead of getting warrior, magnum, or other widely used bittering hops. Low IBU beers often need just a sprinkle and it does the job.

If I want to pick one hop to buy in bulk and use for bittering all my beers, which one would you go with? I mostly brew IPAs and lagers, but am looking for something that’s versatile enough for everything.

Probably the most commonly recommended bittering hops are Magnum and Warrior, the former of which I’ve used extensively. However, I was just chatting with the crew yesterday about how Horizon has become my new go-to bittering variety– solid AA%, really low cohumulone, and a great “hop” aroma. I’m loving it! Plus, it’s really cheap– YakimaValleyHops.com has 1 lb for only $12 right now 🙂

From my experience – high coH older (!!! Not super fresh) hops give this harsh bitterness. Especially on late affitions and dryhopping. For example dryhopping with older cascade from year ago oppened bag would make beer undrinkable. More head 2 head tests could be made on this topic

perhaps the b-acids acting, due to oxydation?