Author: Marshall Schott

The bane of many a commercial brewery’s existence, post-fermentation oxidation is said to have a negative impact on overall flavor stability of beer, reducing shelf-life and leading to profit losses. Because of this, large amounts of effort and money are invested in eliminating as much oxygen as possible from coming into contact with the finished beer. As a homebrewer, I’ll admit to not concerning myself too much with the issue of shelf-life, as the huge majority of beer I make is consumed within 3-4 weeks of packaging, which is typically only 5-8 weeks from the day it was brewed. This is one of the badass benefits of making our own beer! However, I’m aware of many homebrewers who go to great lengths using myriad methods to reduce oxygen ingress at packaging, believing that doing so will extend the freshness of their beer and preserve the precious hop character in styles like Pale Ale and IPA.

I consider my kegging method to be a sort of hybrid closed transfer system where I bottom-fill sealed kegs through the liquid post without purging with CO2 beforehand. My admittedly naïve thinking is that by gently filling from the bottom, the large majority of oxygen is pushed up and out of the keg through the gas post (or PRV for ball lock users), and that residual CO2 in the beer is released via agitations, creating a blanket atop the beer as it fills. I could be wrong, but based on feedback from friends and comments on competition scoresheets, it seems to be working pretty well, as oxidation off-flavors have never been an issue for me. With all the talk lately of people pushing sanitizer out of kegs with CO2 prior to filling to ensure O2-free packaging, I became curious of how a beer packaged with an intentionally poor process would compare to the same beer kegged using my standard method and designed an xBmt to test it out!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer packaged under conditions promoting high oxidation and the same beer packaged under relatively low oxidation conditions.

| METHODS |

Given reports of oxidation having a strong impact on hop character, I decided to double the batch size of the Centennial single hop beer we recently covered for The Hop Chronicles use it to test this variable.

2 Birds, 1 Stone Pale Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 gal | 60 min | 37.0 IBUs | 5.3 SRM | 1.057 | 1.012 | 5.9 % |

| Actuals | 1.057 | 1.012 | 5.9 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| ESB Pale Malt (Gambrinus) | 15.25 lbs | 68.54 |

| Pilsner (Weyermann) | 7 lbs | 31.46 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centennial | 30 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.3 |

| Centennial | 20 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.3 |

| Centennial | 60 g | 15 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.3 |

| Centennial | 60 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.3 |

| Centennial | 104 g | 3 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 7.3 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safale American (US-05) | DCL/Fermentis | 77% | 59°F - 75°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 87 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 125 | Cl 62 | HCO3 200 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

The night before brewing, I collected the water for this full volume no sparge batch, adjusting it with minerals and acid to my target profile, then weighed out and milled the grain.

I hit the flame under my kettle first thing the next morning, adding the slightly overheated liquor to my mash tun for a 5 minute preheat, then mashed in with some help from my adorable assistant, Hazel.

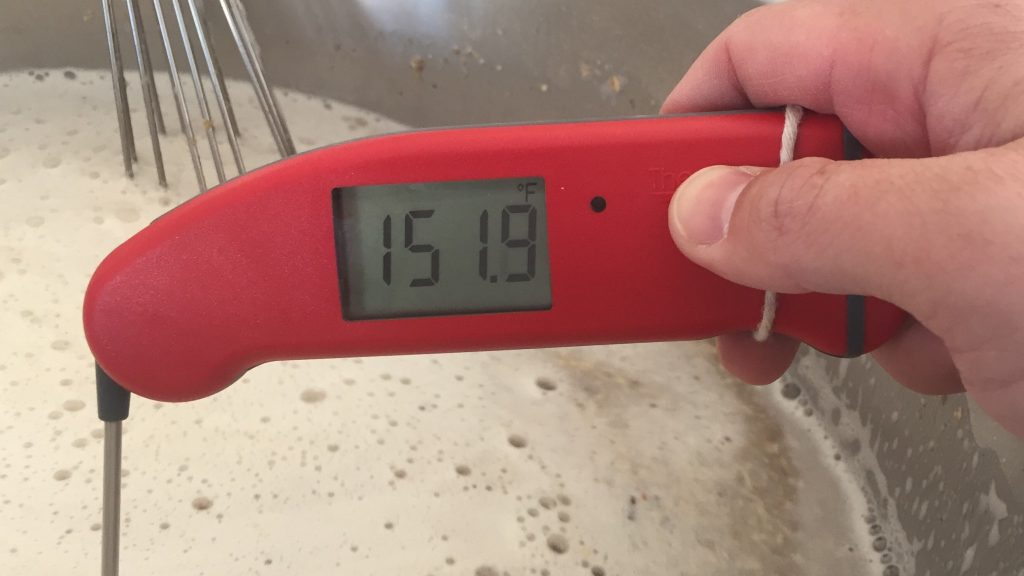

With the grain fully incorporated into the brewing liquor, I measured the temperature and found I was right about where I wanted to be.

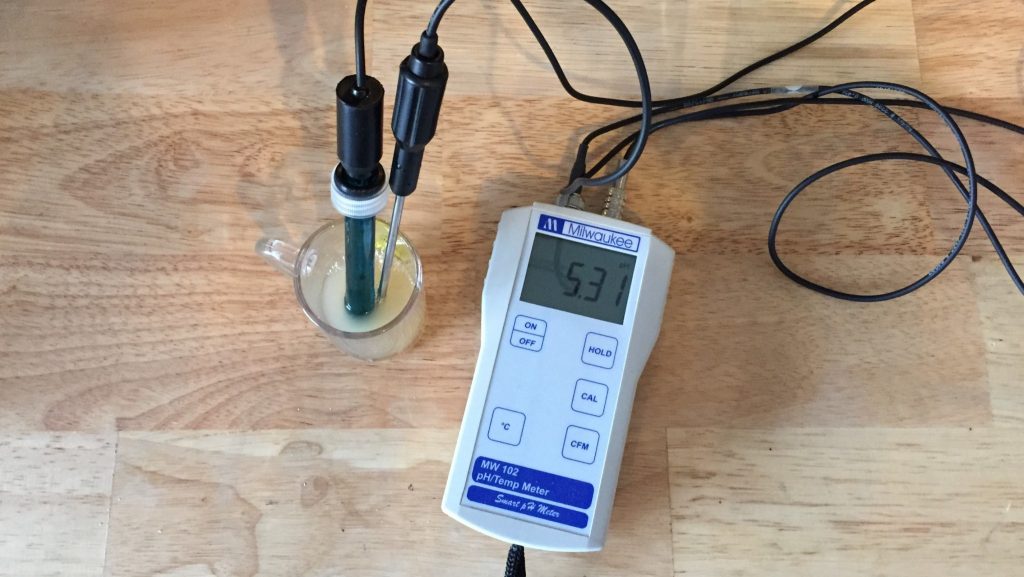

About 15 minutes into the mash, I pulled a small sample for a mash pH reading, it was precisely where Bru’n Water predicted.

After a 60 minute rest, I collected the full volume of sweet wort in my trusty graduated bucket then transferred it to the kettle.

When the wort reached a rolling boil, I set a timer for 60 minutes and made hop additions according to the recipe.

At the conclusion of the boil, I quickly chilled the wort to a few degrees warmer than my groundwater temperature, which was a bit warmer than my desired fermentation temperature.

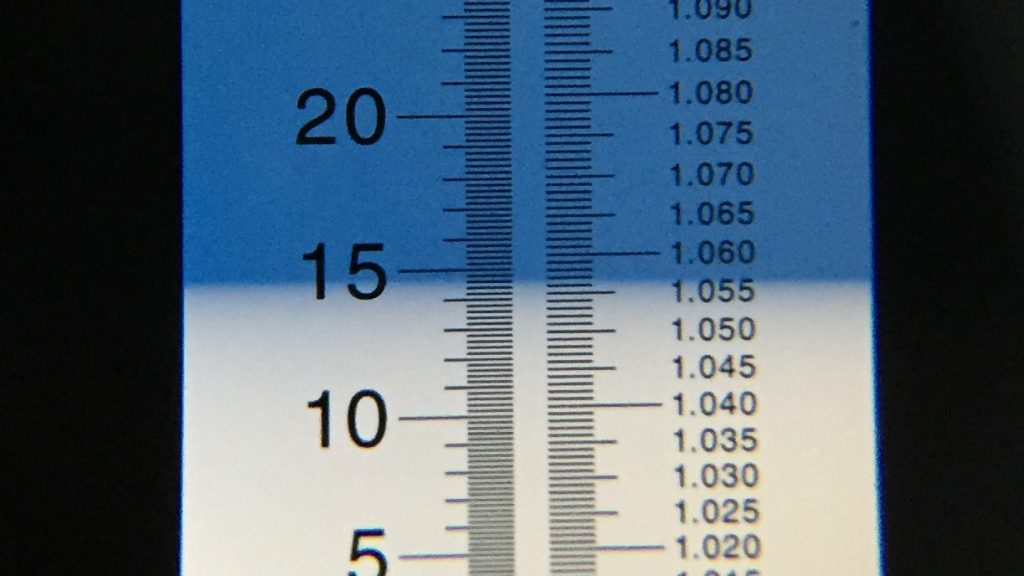

A refractometer measurement showed I’d hit my target OG.

The chilled wort was evenly split between two fermentors and placed in my cool chamber to finish chilling to my target fermentation temperature of 66°F/19°F.

I returned about 4 hours later to pitch vitality starters I’d made earlier with Safale US-05 dry yeast. The following morning, about 12 hours later, I noticed airlock activity indicating active fermentation in both fermentors. I allowed the beers to ferment for 3 days before bumping the temperature up to 72°F/22°C. With signs of active fermentation absent after another 3 days, 6 days total, I took preliminary hydrometer measurements and added the dry hop charge.

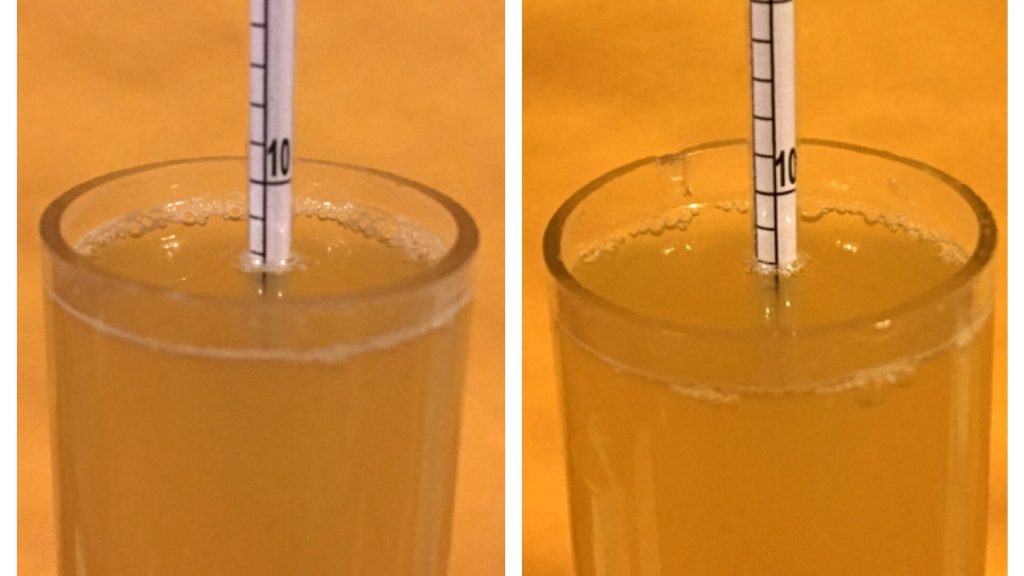

After 3 days on the dry hops, I took a second hydrometer measurement that matched the first, confirming fermentation was indeed complete.

The beers were cold crashed overnight then fined with gelatin before I proceeded to the packaging phase where the variable was introduced. For the normal batch, I used my typical method of transferring the beer from the fermentor to a sealed and non-purged keg through the liquid-out post, a depressor on the gas post to allow air out as the beer fills the keg.

In order to maximize oxidation in the experimental batch, I cut a small length of vinyl tubing, attached one end to the spout on my Brew Bucket, dangled the other end in the unsealed keg, opened the valve, and let the beer splash into the keg.

https://youtu.be/v1u-Qpz2Z8I

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer where they underwent a brief period of burst carbonation before I reduced the gas to serving pressure. Then I let them sit for 4 full weeks because, at least according to many reports, oxidation requires time to really screw a beer up. After a month of waiting, both beers were equally clear and carbonated, not to mention remarkably similar in color.

| RESULTS |

At total of 24 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each taster was served 1 sample of the beer packaged under normal conditions and 2 samples of the beer packaged with high oxidation in different colored opaque cups then asked to select the unique sample. While 13 (p<0.05) would have had to accurately select the unique sample in order to achieve significance, only 11 (p=0.14) chose correctly, suggesting participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Pale Ale kegged with high oxidation from the same beer kegged using more standard procedures.

Since significance was not reached, any subsequent data is ostensibly meaningless, so please interpret the following with caution. Those tasters who were correct on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief evaluation of preference comparing only the 2 different beers. Still blind to the variable, 4 people preferred the non-oxidized sample, 2 said the liked the oxidized sample more, 3 tasters reported perceiving a difference but had no preference for either sample, and 2 felt there was no difference between the beers.

My Impressions: Appearance isn’t an aspect paid attention to during the triangle tests, but it’s something I was very curious about with this xBmt, as oxidation is known to darken beer. Because of this, I fully expected, particularly after a month in the kegs, the high oxidation beer to be noticeably darker than the beer packaged under normal conditions, but that just wasn’t the case, they looked exactly the same. What about aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel? In order to test my ability to distinguish between these beers, I attempted 10 triangle tests, my wife serving me “blindly” and randomly selecting the sample that was unique. In total, I was correct 3 times, no better than random guessing, which is admittedly exactly how it felt. I experienced both beers as one dimensional and boring, though notably clean with no detectable off-flavors.

| DISCUSSION |

Oxygen is real and, despite the results of this xBmt demonstrating tasters could not reliably distinguish a beer that was highly oxidized at packaging from one that wasn’t, I’ve no doubt its effect on beer is equally as real. What I do wonder is the extent to which oxidation during packaging is an issue beer that’s consumed within standard homebrewer timeframes. In a non-scientific poll of a bunch of brewer friends, all of them said the majority of the beer they make is consumed within about 3 weeks of packaging. Of course, it’s certainly possible my normal kegging routine, which it seems is fairly popular among homebrewers, introduces more oxygen to the beer than I thought, though it’s hard for me to believe that amount would be similar to intentionally splashing beer during packaging. And to boot, in discussions with tasters following completion of the triangle test, not a single one described either sample as having any hint of oxidation character, rather the most common comment was that it was clean and otherwise boring, a sentiment I wholly agree with.

These results got me thinking about something that’s been on my mind a lot lately, which is our ability to detect and accurately identify commonly discussed off-flavors. I recall an experience during my BJCP tasting exam where one of the beers, as we learned after the fact, was intentionally oxidized during packaging– apparently, the proctor had another homebrewer who wasn’t taking the exam bottle beers off his taps in a manner that would impart obvious oxidation character. In post-exam commiseration, I learned only one out of about 10 of us noted oxidation (wasn’t me), which at the time I figured others and myself missed because of being overly focused on everything else. However, these days I’m left wondering if perhaps certain off-flavors are more elusive than I’d originally presumed.

Just to be clear, in no way should results like these be viewed as advocacy for a particular method, because they are not. We evaluate variables because we’re interested in learning more about their impact on beer, not because we think people should pay no mind to them. Personally, I’ve no plans to change my kegging practices, as I still view oxidation during packaging as potentially perilous, though I’m now more interested than ever to evaluate the impact of packaging into a CO2 purged kegged.

If you have thoughts on oxidation during packaging or experiences of your own with this variable, please feel free to share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

87 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Cold-Side Oxidation: Normal vs. High Oxidation In An American Pale Ale”

Wow.

Apparently I’m one of the 90% who don’t notice oxidation. I’ve only had one beer in my life that was noticeably oxidized, and it was oxidized as fuck. Like a bottle of sherry left open for six months. Revolting.

This was wild. Thanks.

Yeah, very interesting and encouraging. Guilty of using the second transfer method, although I try not to splash too much.

I wonder if two effects may be at play that protects the beer: 1. There is probably quite some dissolved CO2 that escapes when the beer is splashed, as the container is quite small it is possible the beer is rapidly protected by the gas.

2. Even though the beer was fined and crashed there may be some yeast still around which could scavenge any oxygen that did get into solution.

Lastly I am curious about if we as homebrewers could protect our beers from oxidation by adding antioxidants such as ascorbic acid or sulfite. The latter is routinely added to wine to prevent spoilage from infections and oxidation and could have the same effect in beer, although it would have to be used carefully to avoid off flavors.

Nice work!

For antioxidant protection, I’m following the advice of Geoff Larson up in Alaska: smoke! I’m glad I’ve acquired a taste for smoked beers, apparently they have great shelf life. 😀

Very interesting! I use the same kegging technique as you do, except I purge the keg with CO2 before the transfer.

This xmt makes me a little less paranoid about oxidizing the beer. It would be interesting to see the effect after a longer period of time though.

Do you think the off flavour from exposure to oxygen would be more obvious after an aging of 6 months ore more? This is my main concern when aging stronger beers, I fear this much more than I fear infections, which are less likely to appear in a beer over 9% ABV.

There are so many things it could be– more time, higher ABV, something else. Only way to find out is to keep exBEERimenting 🙂

I often wonder if oxidation is not much of a problem on homebrewed beers because of the reason you stated (quick consumption) but also because of some yeast left. I imagine commercial beers could show oxidation much worse since a lot of it is filtered. Thanks for continuing to do these exbeeriments!

I don’t have the system you have, Marshall, to be able to do a 10-gallon exbeeriment, but I’d love to try this: Do a normal, oxygen-controlled beer, and then another made identically to the first, but hit it with 2 minutes of oxygen from an aeration stone.

In a lot of your exbeeriments you work to maximize the difference of the experimental variable (good practice, that). Maybe oxygen needs to be maximized here.

One other thing (in addition to wondering if the difference will become more apparent over time): what I’ve read is that oxygen has the greatest influence on hoppy flavor and aroma. So i’d wonder if the oxygen-laden beer will fade flavors faster over time, even if there are no oxidation flavors apparent.

David B hits a point I have discussed with a brewery owner. After filtering, oxidation is the biggest issue with shelf life. Filtering is done because the beer is not properly refrigerated, and will be stored warm. Every week they open a can/bottle and taste it, apparently there is clear degradation over time. Another brewer I spoke with that does not filter will not allow their beer to be distributed to shops with warm storage due to the impact to flavor.

I think this exBEERiment could be improved by storing both kegs warm for 4 weeks after its carbonated. This will be closer to real conditions for commercial beer.

These comments always give me a chuckle, the two knee-jerk reactions:. I totally expected that to happen (no you didn’t). And, do something to the beer that nobody ever does. Why don’t you dry hop with cardboard.

This experiment fucking rocks.

I always use the second method although I try not to splash. Never noticed any issues with oxidation. This xbeeriment has just validated my laziness!

I was, myself, having a LOT OF TROUBLE with oxidation. It would darken my beers and the worst part, kill all aroma.

The thing is that, in my opinion, to put it into the test, you should have added a greater amount of DH and choose a more Citric Hop (Citra as an example). For 11 gal, only 100g of DH and being a Centennial DH, that could have hiden something.

What do you think?

I think age kills aroma (hop aroma mostly) even if all precautions against O2 are taken at every step in the process.

I think they brewed a perfectly normal pale ale and changed one variable, which is the point of these experiments. By splashing that much and waiting that long, this experiment was perfect and applicable to home brewing.

Agreed! I am always reading how I should take care with oxidation. If I take some care transferring wort, and drink my beer in 2-3 months, I might never know the difference oxidation makes. And, who lets their beer sit around a year? People who don’t like drinking beer maybe?

I have no experience with oxidized homebrew, but I think it should be interesting to store the beer longer (6 to 12 months) as Draso said above, and specialy to bottle the beer. Maybe the slower reactions in the bottle produce some noticeable effects.

Very interesting blog BTW. It always encourages me to think about my methods and to try something new. Greetings from Chile!

I definitely see the value in repeating this xBmt with bottle conditioned beer that’s been stored longer. Cheers!

As a bottle conditioner with only a dorm-size beer fridge, it’s more the temperature than the storage time that worries me. If those kegs spent the whole month at serving temperature, I imagine any oxidation might proceed much more slowly than bottles in the basement at 66-70F.

i have a four year old bottle of stout that you are welcome to. i am sure it is delicious (not).

Were the beers aged warm or cold? Because that is the other big factor. From an armchair quarterback position, I am tempted to say that a) if warm, they were both equally oxidized, or b) if cold, they were both equally fresh, as it were.

Cold. I’ve never stored beer warm, and if that’s the culprit (which I certainly considered), then perhaps oxidation at packaging really is a concern reserved for commercial breweries.

Good point. I don’t know any homebrewers who store their own homebrew warm, unless trying to age it more quickly, or temporarily for bottle conditioning.

Re: Jason’s point here. I store my beer in bottles at conditioning temperature because I’ve only got room in the fridge for maybe three bottles at a time. So most of my beer sits at 16-19C for a couple of months. I can’t be the only one who does this.

I’m sure you are not, Todd, but the huge majority of homebrewers I know have multiple refrigeration units for storage, fermentation, and serving. I think you are likely in the minority on the warm storage thing.

I wouldn’t worry too much Todd. I keg and keep and serve at basement temp 90% of the time. It’s not particularly warm but at about 50-60 it’s not cold. I have a freezer I’m adapting, but that will mostly be for summer beers which I do like cold. I have never yet had an oxidation problem and I don’t flush the kegs or do anything particular except not to splash. I know it can be a problem because I had a imperial stout from a brew pub that tasted like wet cardboard. It was really obvious and very nasty.

So it has been a slight concern, but I had also concluded that a lot of defects take a while to show up and I just never have beer around that long. I also have had only one case of a beer gone bad and it was the last bit in a keg that got put to the side and forgotten. Maybe 9 months later it was not so tasty, but more old stale than wet cardboard. So that maybe was the start of oxidation?

One thing I get from a lot of these experiments is that what a big brewery needs to worry about because of shelf life and transport etc. is not necessarily an issue for quickly consumed homebrew.

I found this interesting, the formation of (E)-2-nonenal (the cardboard compound), seems to only occur at warmer temperatures: “beers aged at 40C showed above-threshold levels for (E)-2-nonenal after a few days, while beer aged at 20C for four months showed no (E)-2-nonenal.” See: https://beersensoryscience.wordpress.com/2010/11/15/chemistry-of-beer-aging/

It’d be interesting to see what would happen if you kept one of your kegs outside of your keezer.

I’ve still got some of both beer left, and I need room in my keezer. Not sure how much is left, but if it feels like enough, I’ll let them sit in my guest restroom for another few weeks then try them again!

Please do follow up with the results! I also am suspicious that temperature is a large contributer to the oxidizing effect.

Cool test, thank you ! I suppose the few yeast that is left in the beer after fermentation eats the majority of O2 that enters the beer during the bottling steps. So the O2 doesn’t have time to spoil the beer. Interesting would be to see the effect of oxydation on a home-brewed filtered beer (with no yeast left in it) – but that probably doesn’t exist. So it looks like we don’t have to worry about that !

That’s also the reason why you can drink Belgian bottle-refermented beer 5 or more years after bottling while drinking a 1 year old lager can be a disappointing experience.

Thanks so much for this. It is going to make my kegging so much easier.

A minor technical note: you said tasters we unable to detect the highly oxidized beer. Technically, we don’t know is that it was oxidized, only that it was oxygenated. Oxidation is a chemical reaction, but we cannot be sure how much of that really occurred. There are at least two factors we don’t know about relevant to oxidation: how much oxygen dissolved as a result of splashing? What’s undissolved will be removed at purging. Second, does yeast metabolize the oxygen, preventing the chemical reaction?

Any chance of running this one again with a purged keg vs non-purged, similar to the Experimental Brewing one thats happening at the moment.

Agree

This goes back to what ive posted on HBT and got blasted for pretty much. That oxidation is the new “buzzword” on that particular forum. I just dont think its that big of a concern in my opinion on a homebrewing scale. Our consistency is never going to be commercial level quality no matter how good we are. Also our timetables for how quickly our beer is consumed is MUCH quicker.

I also stated that maybe its an issue for something like a competition where there are more refined palates judging ones beer, but frankly Ive never tasted one of mine that was oxidized and im not honestly sure what that tastes like.

Im palate dumb so ive never cared about all these crazy ways or minimizing o2 input. Jam it in the keg, purge the headspace a few times call it a damn day and drink my friggin beer.

I agree 100%. Every hobby has it’s members who love to play in the extremes though. you should see some of the conversations on oil in the motorcycle forums I frequent. LOL

A friend of mine has a very discerning palate. He tastes things in beer I cannot.

I’ve never tasted oxidation in my beers, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. I also couldn’t taste the apricot in a commercial beer that my friend insisted was there (it is in the recipe, so I believe him. 🙂 ).

My beer, other than some Vanilla Porter aging in bottles in my basement, is always cold once it’s packaged.

Having had an oxidized beer at a pub, I don’t think you will miss it if you ever come across it. It’s a really nasty taste.

Consistent quality I all for, consistent beer flavor not so much. I have my repeater recipes but I tend to change the hops periodically. I don’t want to drink the same beer over and over again. If I wanted that I would be buying it.

I’ve definitely had oxidised beer. Had to throw away my auto-syphon because loads of air was getting in and spoiling the beer during transfer. I don’t know if purging the keg matters or not but I’m not taking any chances after the improvement in my beer since I changed my packaging methods.

I wasn’t surprised at the results. This experiment is comparing two beers that we’re both oxidised, hot and cold side, therefore there should be no difference between the two. The dry hop was a big offender on the cold side!

I will be interested to see a side by side of a true highly oxidised batch, using either method employed in this current experiment, to a no oxygen batch. No oxygen meaning transfer from fermenter to a properly purged keg and natural carbonation, or spunding, in said keg.

I agree. I wouldn’t worry as much about hot side. But on cold side, cold-crashing without backfilling it with CO2 would already introduce plenty of oxygen exposure. More than for dry hopping (if done properly) in my opinion.

they are both equally oxidized, and unpurged keg may contribute a bit more oxidation potential, but probably not substantially so. As long as beers are kept cold, and served quickly, I doubt oxidation can be noticed by most people.

I think the key exbeeriment is the CO2 purged keg vs. the splashed keg.

Fantastic experiment. I do method two every time, but with care not to splash. I’ve never worried about it much, being a disciple of Charlie Papazian, but lately, as someone mentioned above, homebrewers have gotten nutty about O2 ingress. The method of filling your keg completely with sanitizer, then pushing it out, and then filling an Co2 rich keg seems mind-bogglingly complicated and time-consuming. Didn’t we all buy kegging systems to save time and effort? I haven’t noticed any undue oxydized flavors, but I have also wondered if my ability to sense this off flavor was poor. My take on things– yes, a Co2 blanket on top of the beer must be quickly established, and also, I think the yeast present in homebrew scavenges yeast very quickly. Lastly, on a commercial scale, their bright tanks are huge, and the surface area of beer being racked over from the fermentor is probably equivalent, at just a few inches depth, to an entire batch or more of homebrew. Thank you so much for doing this one.

Not to mention expensive– CO2 ain’t cheap!

Just to clarify a couple of points. For our homebrewing applications, there is no such phenomena as a CO2 blanket. Any gases present will mix.

Also, my understanding is that yeast will not scavenge oxygen unless they are actively consuming sugars, converting them into alcohol and CO2. I don’t think the yeast sit around and say “Hey, there’s some oxygen! Think I’ll have that for lunch.”

I was under the impression they scavenge what they can, even when not actively fermenting, to prepare for the next round of growth. I think they store up what they can in anticipation of another cycle. Someone correct me if that’s inaccurate.

The problem is that they don’t scavenge much. You need several points (like ten or so, not sure exactly) of sugar to eat it all. Otherwise oxidation would not be a problem in bottle carbonated beer – containing yeast and priming sugar. I think storing the beer longer (and at room temp to speed it up), as I saw a bit up in the thread that Marshall will try, will reveal something else than the currently reported outcome.

I did a bit of reading over the lunch hour.

https://www.morebeer.com/articles/how_yeast_use_oxygen

Things I learned: One brewer’s yeast do not need O2 for fermentation in the presence of sufficient nutrients, because it does not need to respire. Two, after pitching the DO levels in wort drop to near zero within 30 minutes. Three, the yeasts use this oxygen for sterol synthesis.

So it sounds like yeast’s consumption of oxygen is not dependent on active fermentation. However, I would also postulate that the uptake of oxygen seen at the initial pitch of yeast into wort is not repeated every time there is oxygen introduced into the wort. If that were true, we’d never taste an oxidized homebrewed beer.

I think we need to classify oxidation into two categories: malt and hops.

For the malt, we get what you were looking for. Long-term instability with wet cardboard/sherry and darker beer. I’m not surprised it takes more than four weeks, but a bit surprised with that hard oxygenation, even though some explanation can come from the fact that foaming could introduce a co2 environment itself (compare that to bottling, where every bottle is not purged).

For the hops, in particular, oxidation of essential oils. Those that I think you lacked in both beers? I’m talking juicy NEIPA-character. And I think you didn’t have them for four reasons: opened fermenter after fermentation to add dryhop and introduced oxygen in the headspace, didn’t transfer to purged keg, cold crash airlock suck-back (more than you think, see general gas law). Last but most important: four weeks is a long time if you have oxygen in there, we’re talking days with oxygen for this response variable!

I have done my own, not so scientific, experimentations with the hop oils. I’ve noticed differences between muslin bag vs. stainless, fermenter hopping vs keg hopping, whole hop vs. pellets. The difference is however most noticable between four to six days post dryhop. In these cases, I also introduced oxygen in the three ways described above. I think the four to six days could be increased to a month, like some (but very few) breweries manage to, and I will test that when I make my next hop-forward beer.

Also, hop bitterness tend to fade away with time, but I’m not sure that is a function of oxygen. It is, however, separate form the first form – this is not what I mean and it often gets confused.

In conclusions: in order to make a purged keg vs. open experiment as good as possible, make sure to avoid the other oxygen introductions. Then you can shut me up 😉

Okay, but how can you avoid O2 from dry hopping (juicy NEIPAs are certainly dry hopped), and airlock, or even blow off tube, suck back?

1. Dry hop at day 2 or 3 into fermentation. 2. Transfer beer to another keg (spunding keg) with a little extract left. Let the keg pressure up as the yeast finish off the sugar. Then cold crash. No suck back will happen.

Another option for preventing suck back is to let the beer finish fermenting in primary, transfer to a clean and purged keg, prime and let the beer naturally carbonate in the keg, then cold crash.

That will be the challenge! For the airlock, I’m thinking about putting a bag on the airlock and let fermentation fill it with co2. I’ve been looking at the kind of bag-in-box bags for wine, but not sure what will be the winning solution here. Some people use condoms as “airlocks”, maybe putting that on top of the airlock? A side note here is that a cold crashed beer will consume co2 that will go into solution, so the co2 blanket (that I think people are bullshitting around with a bit too much as a holy grail anyway) will get sucked into the beer. How much – I’m not sure at atmospeheric pressure (maybe even negative, so the reverse is happening?) – but it could be something that creates suckback too. Compare with the method where a keg is hooked up to gas and shaken for a few minutes to carbonate it, how much co2 it drinks! Of course, the cold crashed beer is not shaken, but it shows how much co2 really goes into a carbonated beer.

Now, adding the hops… this is where it gets tricky. Some commercial breweries put them into a stainless container and purge with co2, then inject them inte the beer, or even better circulate beer through them (see e.g. “torpedo”). Agitation helps to extract as much oils as possible in relation to as little grassiness (chlorophyll) as possible. I’m thinking about racking to purged keg with the hops in there, keg hop, then transfer to another keg. As a side note: if using no too much hops (<100 g per keg), it seems to be OK to leave the hops in there forever provided that the keg is stored cold (6 C for me). Not enough grassiness extraction happens for it to be a problem with this amount of hops-to-beer and the cold temperature.

Check out the massive NEIPA thread on HBT for details on all of that. Short version is dry hop #1 goes into the beer while it is still actively fermenting, the active yeast will scrub out the introduced O2. Dry hop #2 gets added to a CO2 purged keg, sealed up and purged some more, then closed transfer the beer into the “dry hop keg”. This is where cold crashing also takes place. Finished beer is pushed from the dry hop keg into a purged serving keg.

Some guys will also add priming solution to their kegs and/or transfer to a keg with a few points left to go to OG. Beer finishes up with a spunding valve hooked to the keg. How deep down the rabbit hole do you want to go?

Three years ago I climbed out of the rabbit hole after 7 years inside. I stayed in the light for 2 years, not brewing at all. I even sold my “The Electric Brewery”. I’m back at it now with the goal of simplifying everything I can so it stays fun this time. #noobsession

Yes, that are also alternatives. One need to be aware of the possible problems, that don’t need to be problems if accounted for:

* Adding hops to active fermentation decreases yield as yeast clings to hops

* Also, oils are volatile => they bubble away quickly with co2.

* Adding hops to active fermentation (or, yeast in suspension at fermentation temperature, I guess) changes flavor profile as yeast eat the sugar in some sugar-oil compound molecules and thus release new oils. This might be good, or bad. It depends on what aroma/flavor you want =)

* Racking beer off yeast cake too early can be problematic, make sure to motivate keep yeast to stay longer in suspension by raising temp to reduce acetaldehyde and possibly diacetyl. Should really be done anyway.

* Spunding may trap some things that should not be there, like certain sulfur compounds. Choose yeast appropriately.

The great thing about yeast+sugar is that it eats the oxygen as long as there is enough sugar in there (tens of points and more). So, this is certainly an alternative. The problem is letting the fermentation complete enough before racking vs. keeping dryhop contact time low as to not extract grassiness at these temps.

Crazy experiment idea: see if grassiness extraction happens slow enough at, say 10 C, and use a lager yeast to fininsh off fermentation (or really, use it all the time, maybe even abuse it a bit to create ale-character).

Kyle P: Interesting. Seems to be over-doing it a bit, as you hint 😛 I think double dry hopping even might a waste, as oils fade quicker than grassiness and you introduce more grassiness-to-oils. The hops I can source locally are not that good either, or so I believe at least, they are not always in their freshest state (much grass and skunk, little oil). Some bags I’ve opened have been dry and smelled cheese, it sucks, can’t dryhop with that.

Marshall: sure it has. My quest for good hops strated long before I knew what NEIPA was. And I even think adding adjuncts to prolong haziness can be problematic, when we’re talking stability and all that. Sure, it is good for breweries, as beer look “hop haze fresh” longer and consumers drink with their eyes. I’m certainly guilty to that too, I also drink with my eyes. But, if I knew the beer had a better taste even though not looking hazy, I’d take that one. I think it’s deeper than how it looks – it’s also about social values – about beer culture.

I used to dry hop on day 3 for this reason. I’m not quite getting the transfer thing though. Are you adding a bit more sugar, or just transferring before the beer finishes completely. Most American ales are finishing on day 3 or 4 for me, so that would give very little time on dry hop.

The idea is that oxygen is added when you toss in the hops. So dry hop on say day 3 with active fermentation still going. You can then leave the dry hop as long as you’d like before transferring to a keg.

Either way works. Some folks transfer to a keg before the beer finishes, especially with slow fermenting lagers. But as you point out, for many ales things just progress way too fast to do this.

Lately I’ve been priming my kegs to naturally carbonate, just like a bottle. I do this because I just don’t have time mid-week to spend much time on beer related activities, such as timing fermentation just right so that I can transfer to a clean keg with a few gravity points left before FG.

Good stuff. I don’t want you to shut up! Also, fear of oxidation has been around a lot longer than NEIPA.

Based on the ideal gas law, a change in temp from 22 to 0C, 2gal of fermenter headspace would require a total 0.15gal of replacement air volume, equivalent to 0.03gal (118mL) of oxygen (20.9% O2 in air) being sucked back in.

This would be for an airlock (and fermenter seal, etc) being practically non-functional. I would suspect that the airlock could withstand at least some level of negative pressure, therefore reducing the maximum possible amount of O2 reintroduced above. The maintenance of negative pressure would also minimize the dissolving of the gasses into liquid.

Certainly not making a judgement on the effect (dose-response relationship) of any suck-back on final beer, but it ‘seems’ like a small amount next to the other factors mentioned. And based on the results of the Xbmt, maybe not such a big deal.

Did you kept the kegs in room temperature? Oxidation won’t happen in the cold beer.

Perhaps it’s less likely to happen, but it certainly can in cold beer. I kept the beers in my keezer, as I see not reason to store beer warm. That said, I see the value in retesting this using warm stored beer 🙂

Good experiment.

I would like to see it repeated with maybe an 8 week wait time rather than 4. I think 4 weeks seem within a reasonable shelf life to me.

Also it would interesting to see how one of the newer hop varieties like Simcoe, Citra, Amarillo, etc would fare. IMO Centennial can hide some of the flavors I pick up with oxidation. Centennial can be woody earthy etc, which may even be confused with oxidation flavors.

I think the bright flavors you get with the new strains would be easier to pick out oxidized flavors, but some of the that brightness would be lost with time as well.

Would it be possible to compare fresh beer with old oxidized beer? I’ve done side by sides with fresh vs old beers from the likes of Heady, Maine, Lawson etc. Sometimes its just the hop flavor that fades, but sometimes there is a very apparent oxidized flavor.

Great job on the experiments, btw! I look forward to them…

I share the concern re our ability to detect many off flavors at lower thresholds. Suggestion: an experiment that ensures that oxidation is at an extremely high level (use an oxygen stone after filling in this case – perhaps on several samples that have been drawn off. Test at several points in time after bottling. thinking about this perhaps just do this at bottling time if one is a bottle conditioner. And since we are talking about creating an off flavor, perhaps this can be done with uncarbonated/unconditioned beer. I recall a BHB episode that explored hot-side aeration where they virtually whipped the beer yet got no detected result. Truly a mythbuster.

Using an oxygen stone? The point of these experiments is to be applicable to home brewing and be within the realm of possible methods – except for the time they innoculated with diacytal.

It’s funny to me to put so much thought into why there was no difference here and if it means there is no such thing as oxidation, etc. This is one test of one batch of beer with one group of people, like most XBMTs. If you drink beer fairly quickly, it is likely ok to use either method to rack your beer if you aren’t super sensitive to oxidation. Not much more we can conclude I would think.

I’ve just finished a batch of Belgian Dubbel that I bottled October 2014 and stored outdoors in a shed – cold in winter, warm in summer. It tasted great right to the end. Definitely a hint of sherry. No wet cardboard.

It might be different with very hoppy pale ales, but I think fear of oxidation on brewing forums is bordering on pathological.

I’m curious how this would differ from bottle users. Those that back pressure full vs those that just fill with a standard hose and bottle filler. I think the oxygen per oz in the bottle would be higher than a keg in general due to the number of containers and the overall surface area and hence more of a concern for bottlers. The surface area of the keg is pretty small compared to the overall volume of the keg.

Great Xbeeriment that I will definitely use to refine my brewing process.

Bottlers also prime with sugar rather than force carbonating, so there’s a second fermentation that might well scavenge any oxygen introduced at bottling.

I’ve done countless comparisons in my homebrew club. Bottled super hoppy IPA never is as good as kegged. It is certainly oxidized. That would be a good XBMT too.

I explored this recently after two batches of hoppy beers oxidized very quickly and noticably. I bottle condition all of my beers, which obviously leaves much more room for oxygen exposure through the packaging process. While I don’t have a kegging setup, I do have a sodastream, and decided to test if purging my bottling bucket (as well as I could), individual bottles before filling, and the headspace of bottles after filling and before capping made a difference in preserving a big hoppy aroma and flavor. Before I start, (1) yes I know I should just start kegging and (2) I know this isn’t a controlled/rigorous experiment like the articles written here.

Long story short, there was an obvious difference even 2 weeks after bottling between the bottles that were purged before and after filling and bottles only purged before filling (without headspace purge). After a month, even bigger difference was noticable. The double-purged bottles maintained a big, citrusy hoppy aroma and flavor. An unpurged bottle had minimal hop aroma and had the characteristic stale/cardboard taste of oxidized beer. The bottles purged before filling but not the headspace were in between (lacking big hop aroma, but not yet tasting like cardboard).

It is a lot of effort to purge all the bottles when filling, but in my experience it makes a huge difference and is worth it for me.

Wow! Awesome comparison! I think people should maybe look at getting a CO2 cylinder and a Beer Gun if they can’t switch to kegging yet.

Bottled vs force carbed in keg exbt already done – no difference detected. Also hoppy IPA force carbed in keg vs naturally conditioned in keg, again no difference detected.

Bottled hoppy IPA vs force carbed keg might give a different result. Lots of brewers say bottled beer is rubbish, so it would be an interesting comparison.

I transfer with as little splashing as practical into a cold CO2 purged keg and was considering going to closed transfers but I sure ain’t doing that change now. I could see cold transfers just because the cold tubing can be difficult to keep down in the bottom of the keg and it’s a sticky mess to deal with when done. I worry about tracking the level of beer going into the keg when you can’t see it though. I kind of want to see how much I’ve got.

The one time I suspect oxidation – I was messing around with a half filled keg and accidentally left it out at room temp for a couple hours with the lid cracked – I recarbed and chilled – yuck!

Possibly a dumb question, and totally unrelated to this experiment. But with your keg filling technique, how do you know when it’s full?

i use a bathroom scale

Conventional wisdom says that yeast in bottle-conditioned beers will consume any available oxygen, but the Crabtree effect applies for concentrations over 0.2% and 3 grams in 350mL is 0.8%. Perhaps more than a typical experiment, real data would be useful. A comparison of dissolved oxygen levels for different bottling and kegging routines would be useful, as well as with/without oxygen-absorbing bottle caps. One home-brewer recently commented that the aroma of his bottled hoppy IPA after one month went from almost nothing to remarkable after he started purging the bottles before filling and the headspace after filling. Maybe one of the contributors with ties to a brewery could use their laboratory?

Yeast will still scavenge oxygen during anaerobic growth because they need it to manufacture ergosterol and fatty acids for cell membranes, so the Crabtree effect doesn’t matter.

The main reason hoppy pales have more aroma from keg is that they’re usually served younger. Cold crashing and force carbing mean you can serve within a few days of kegging, whereas bottled beers need at least 2 weeks to condition. During that time, the intense flavours from dry hopping start to fade.

Another cold hard truth bites the dust. Thanks! To stray a bit from the topic of this xBmt: Can you describe your method of making a vitality starter with dry yeast as you mentioned in this article? I guess plain old rehydration and then on as described in the xBmt about the vitality starter?

I have been home brewing for 1 year exactly now and I bottle my beer (it’s bottle conditioned).

I like every single beer I’ve brewed more now than the day I bottled it. Perhaps that is because I am a fan of Belgian and german beers and the higher the gravity the more I tend to gravitate towards it. But everything from a 10% honey golden strong to 5% hefe’s to 6% milk stouts I find to taste better months in then fresh.

I honestly don’t even know if I know what oxidation tastes like as no one has ever pointed out an “oxidized” beer to me. I’ve had beers anywhere from fresh (obviously) to 10 years old and they obviously taste very different but in almost all cases I prefer the oldest versions I’ve had.

I think oxidation is one of those things that is WAY WAY WAY over-thought by home brewers in particular.

For IPA drinkers I can understand liking fresh beer over aged beer… pilsners/kolschs too… but luckily for me, I hate those styles and don’t drink them. All the styles I like age amazingly and 1-2 years from now will only be better than the day I brewed them. My taste buds make my brewing and drinking life way easier 😛

I’m like ^Ben… been brewing for a year, bottle conditioning.

I am relieved at the results of this xbmt.

I read about putting the fermenter under CO2 pressure as you empty it to keep the beer from oxidizing and I’m thinking…? Really? If this hobby got any more complicated in order to achieve tasty, drinkable results I’d leave it to people who aspire to be quantitative chemists. I have to rack from fermenter to bottling bucket where I stir the beer to evenly distribute the corn sugar prior to bottling. The bottles are full of ambient air prior to being filled with beer from a bottling wand. I am careful not to splash or agitate any more than I have to but my beer hardly avoids contact with oxygen in the process of transferring OR in racking from primary to secondary.

Again, glad these results are what they are. My technique may drive the brewing “type As” who get all excited about oxidation insane, but I produce tasty, drinkable brews and my Heffeweissen and my Grapefruit IPA game are strong 🙂

I will submit what I think a rather strange occurrence that happened on two different occasions, once over a decade ago, and once two years ago.

The first was involving a ‘Bellhaven Wee Heavy’ recipe from ‘Clonebrews’, and the second was involving a Rauch Schwarzbier. The wee heavy fermented from 1.072 down to 1.01, something that I attribute to way undershot mash temperatures (cold, blustery day). I can still taste the peaty

smoothness that I would liken to a single malt scotch. From the final gravity, it should be obvious that there were not a lot of flavors competing with the heavy (but not unpleasant) alcohol presence and the absolutely wonderful peaty character. I have not been able to replicate this phenomenon since. Yes, I have tried.

The Rauch Schwarzbier was brewed with 44% rauchmalt on 12/5, racked to 2nd on 12/17, kegged on 3/15, and drank on 5/1. The first taste was of smoked sausage, and I was absolutely astounded, so much so, that I had to try another, and another… to make sure that I was not imagining this wonderful flavor in the beer.

In three weeks the flavor turned to cardboard. Even though there was hardly any left (I am a weekend-only drinker), I was totally WTFing. I recalled that the same thing happened to the wee heavy years ago.

During racking of the rauchbier into the keg, I used a ‘pump’ siphon that forces the bier up into the siphon. I had to pump it like 5 or 6 times to get it to flow, and I’m guessing forced a shitload of oxygen into the beer. In this beer there were no nasty flavors that I attribute to the dark grains. And I wonder if perhaps I oxygenated the wee heavy years ago.

The first thing that I did was buy a sack of Weyermann Rauchmalz, because I was going to brew that beer again ASAP. The rauchmalt in the sack did not have nearly the smoky flavor as did the rauchmalt in the 1 lb. plastic bags. Both were Weyermann.

After brewing the beer again, I was left with none of the smoky goodness and a quite nasty flavor from the dark grains.

So I bought a sack of Bestmalz rauchmalt. I smelled it. Aaaah, that wonderful smoky aroma. Surely this would make good beer. I will leave out the nasty dark grains and use 64% of this rauchmalt this time. Not even a whiff of that wonderful smoke that I was after in the finished product. It smelled great in the sack, but gave no smoke flavor or aroma whatsoever to the beer. What it gave to the beer was a very shitty flavor that I would NOT describe as band-aid flavor. I suspect that they malted the grain with chlorinated water, because my brewing water was absolutely chlorine free.

I brewed a beer with grain that I smoked myself, and it lent a very pleasant nastiness to the beer, but was nothing like what I was after. I now have lagering, a beer with Weyermann rauchmalt that was purchased in the smaller quantity bags. If that is no different, I will brew one with 90% rauchmalt.

I posted this here in the off chance that someone might have a clue about what happened to the wee heavy and the first rauchbier, that they were the absolute best for about three weeks, and then, cardboard (oxidation?). The rauchmalt info I included because I figured someone might be thinking about buying Bestmalz rauchmalt.

Pete

Mr. Schott:

Both beers are likely oxidized. Your standard method of transferring to a keg filled with air introduces oxygen into the beer. You must fill the keg with sanitizer (or something clean) and expel the contents with carbon dioxide before filling it with beer if you want to avoid oxidation during the transfer.

You probably also had air introduced in other places which would oxidize both beers, but I don’t believe you tested the transfer step adequately in this experiment.

A valid presumption, indeed. You LODO?

Great exbeeriment as always! Love reading these and they are so so soooo informative. I was always concerned about oxygen when kegging from everything I read but now I’ll be a little more at ease. I tried your method a couple of minutes ago transferring water from my brewbucket to the liquid out on my keg and it stopped about two gallons in. What the heck am I doing wrong? I wanted to do a trial run before brewing and I’m sure glad I did.

Thanks for everything you do!

Dude I read all of these responses … all of them. Halfway thru I felt more educated on the subject ( and I do not miss and exbeeriment write up ) and now after finishing I am more confused. Balls.

Sorry to rehash an old post…… I had an interesting experience. Brewed in a brew bucket with 105g of hops hot side and 114g dry hop. Cold crash 2 days, and then closed transferred to a purged keg.

Have a carbonattion stone in the keg, carbonated for 24 hours in the keg fridge and tested. Good carbonation and great taste but slightly disappointed with the aroma. Turned off the gas and tested again tonight, all of the aroma and flavour is gone. Thought the beer has darkened but comparing pics from the day after confirmed a similar colour.

Gut feel is beer might be oxidised, not sure how or whether it would oxidise that quickly. Upon reflection, could turn the gas off cause the CO2 to be absorbed and O2 introduced?

Cheers,

Jase

Perhaps a good experiment would have been to let one fermentor simply ferment with a wet towel sitting on top of it, or at least no airlock, and the other one in the closed keg. No dry hop additions to either to avoid oxidation to the keg, and then cold crash both fermentors before packaging, in either bottle or keg. Now that would be interesting to see the results. I am wondering if exposure to O2 over the course of cold side fermentation has a noticeable difference. I suspect it would, but I aint going to waste a half load of beer to check test it. 🙂

My question would be – do short bursts of oxidation (say from dry hopping) matter as much as prolonged O2 exposure. And how much?