Author: Marshall Schott

In his book Brewing Better Beer, the great Gordon Strong likens roasted grains (roasted barley, black patent, chocolate malt, etc.) to coffee, explaining the temperatures at which they’re roasted are high enough to denature any enzymes, meaning they do not need to be mashed. Not only is mashing roasted grains and malts unnecessary, but Strong adds it “can lead to harsher, more astringent flavors in the finished beer.” He does mention this is to some degree dependent on water chemistry, though concludes, “regardless, the dark grains are exposed to the most heat during this method, and that can lead to a harsher bitterness in the finished beer.”

Strong goes on to discuss different methods for using roasted grains and malts such that these undesirable characters are avoided, one of which involves adding the roasted grains to the mash toward the end of the saccharification rest, a technique referred to by many as capping the mash. In the book, Strong suggests adding the milled roasted grains at mashout then performing a recirculated vorlauf, effectively treating them like coffee in a drip machine. Obviously written from the perspective of a fly sparge brewer not wanting to disturb the grain bed, many modern homebrewers have adapted this method for batch sparge, no sparge, and BIAB and report similar results by stirring the roasted grains into the mash during the last 10 or so minutes of the rest.

I was first inspired to try this capped mash method after my scoresheets for a Dry Stout competition contained the words “astringent” and “acrid.” To me, the subsequent batches were good, maybe even less astringent and acrid, so I adopted this method without much consideration, convinced it was improving the quality of my Brown Ale, Porter, and Stout. Of course, bias may have (absolutely did) played a role in my perception, so when my desire for a low ABV roast-heavy beer began to creep up, I knew exactly which variable it’d be used to investigate!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a Stout where the roasted grains were included in the entire mash and one where the roasted grains were added in the last 10 minutes of the mash, during the vorlauf step.

| METHODS |

Curious how rye character might play with roasted grains and looking to get a bit more body than flaked barley usually imparts, I designed a simple Stout with a twist.

dRye Stout

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.3 gal | 60 min | 36.7 IBUs | 36.0 SRM | 1.039 | 1.008 | 4.1 % |

| Actuals | 1.039 | 1.011 | 3.7 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, Maris Otter | 5 lbs | 58.82 |

| Barley, Flaked | 1.25 lbs | 14.71 |

| Rye Malt | 1.25 lbs | 14.71 |

| Roasted Barley (Simpsons) | 1 lbs | 11.76 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnum | 20 g | 45 min | Boil | Pellet | 11.2 |

| Fuggles | 30 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 5.2 |

Miscs

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride | 3.00 g | 60 min | Mash | Water Agent |

| Gypsum (Calcium Sulfate) | 1.50 g | 60 min | Mash | Water Agent |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Diego Super Yeast (WLP090) | White Labs | 80% | 65°F - 68°F |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

While a certain Irish strain of yeast is a popular choice for this style of beer, I wanted to see how one of my go-to yeasts would perform and built up a large starter of WLP090 San Diego Super Yeast a couple days before brewing.

Since I would be performing two separate mashes, which I staggered the start of by about 20 minutes, I went with the no sparge method and collected the full volume of brewing liquor for each 5 gallon batch.

As the water for the first batch was heating, I collected and milled the grains, holding back the roasted barley from the capped mash batch to crush on its own.

With the grain milled and water hot, it was time to mash in. Despite the 1 lbs difference in grain weight between the mashed and capped batches, the strike temp was very similar and both mash temps were consistent.

The hour-long saccharification rests commenced.

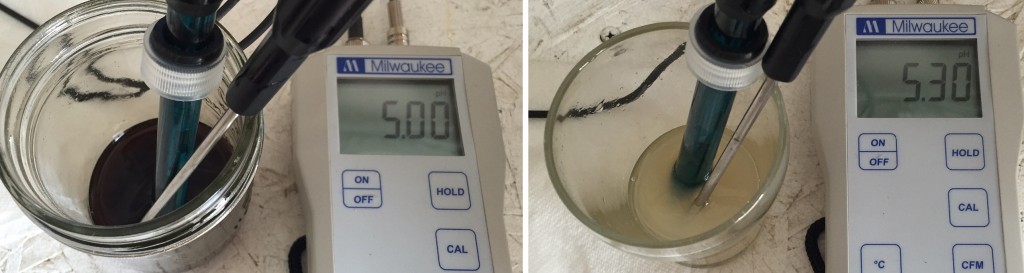

Approximately 15 minutes into each mash, I took pH readings and found my expectations were met. Wort from the batch with the roasted barley, known to increase mash acidity, was at a low 5.0 pH while the capped mash wort was at a perfect 5.3 pH.

About 15 minutes after collecting the sweet wort from the full mash batch, as it was coming to a boil, I “capped” the other mash with the roasted barley previously reserved and gave it a good stir.

After 10 minutes and 2 more brief stirs, I collected the sweet wort from the capped mash and brought it to a boil next to the already boiling full mash wort.

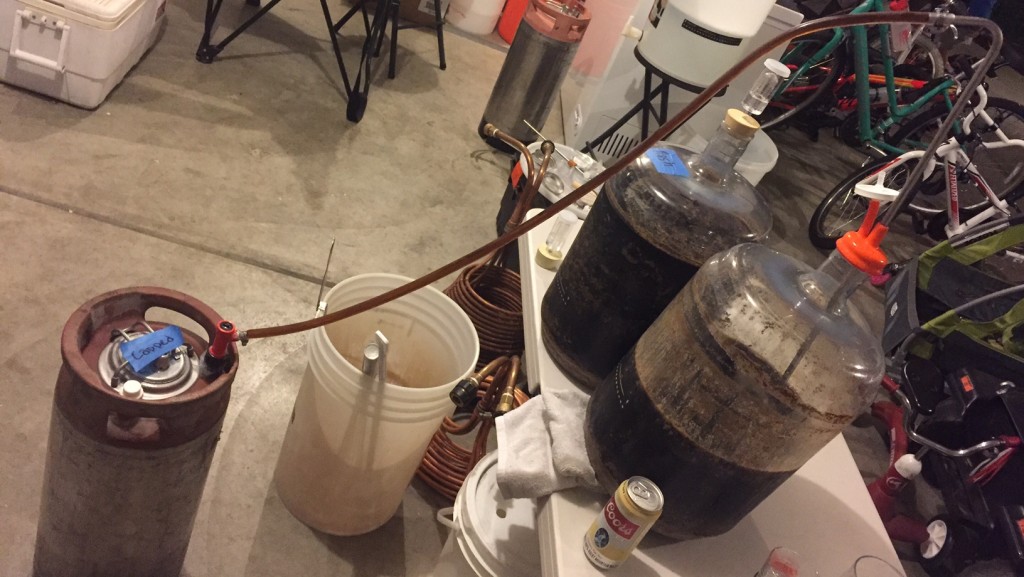

Both worts were boiled for 60 minutes, quickly chilled, racked to 6 gallon PET carboys, then placed in my temp controlled chamber where they sat for about 2 hours before reaching my target fermentation temperature of 66˚F/19˚C. The yeast was then equally split and pitched. I returned 18 hours later to find the beers fermenting as expected.

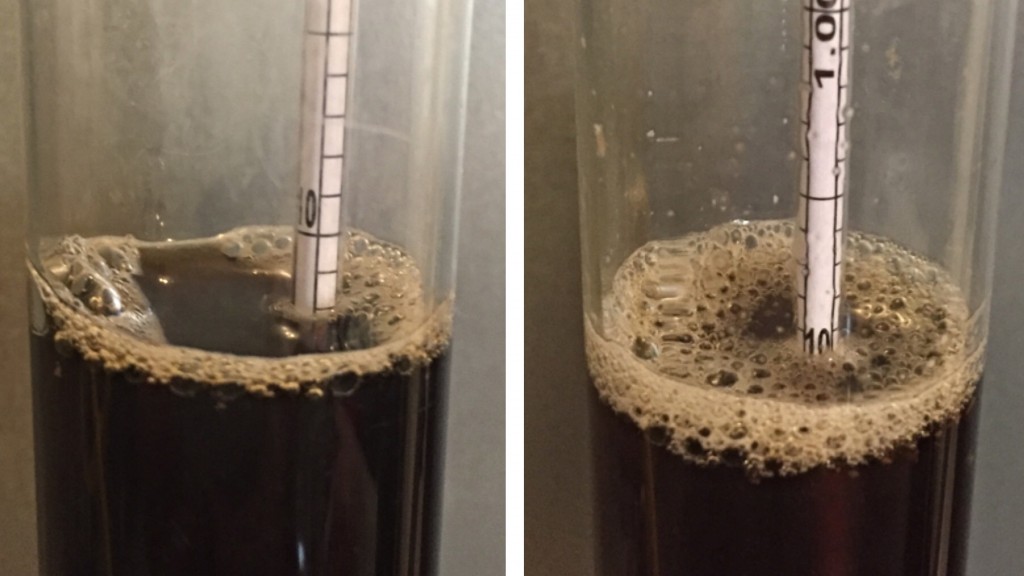

Besides the capped mash beer having a slightly paler kräusen, fermentation for both beers was observably similar. I took an initial FG measurement about a week after pitching the yeast, it matched the hydrometer reading 2 days later that showed the full mash beer had finished slightly higher than the capped mash batch.

The beers were then crashed for a couple of days then kegged and left to carbonate in my keezer for a few more days before being served to participants.

By data gathering time, both beers were looking awful nice, though their color was noticeably different.

| RESULTS |

A total of 22 BJCP judges, experienced homebrewers, and craft beer lovers participated in this xBmt. Each person was served 3 samples in different colored paper cups, 1 from the full mash batch and 2 from the capped mash batch, then asked to select the different beer. To reach statistical significance with this sample size, 11 participants (p<0.05) would have had to accurately select the full mash sample as being unique. Exactly 11 (p=0.049) made the correct selection, suggesting tasters were reliably able to distinguish between a beer made with roasted barley included in the full mash from one where the roasted barley was added during the last 10 minutes of the mash.

The 11 participants who made the correct selection on the triangle test were asked to complete a brief evaluation comparing only the 2 different beers, remaining blind to the nature of the xBmt. Overall 5 of the tasters preferred the full mash beer, 4 liked the capped mash beer more, and 2 had no particular preference. The independent variable was revealed and participants were offered an explanation as to how this technique is purported to impact the beer, then they were asked to select the sample they thought was produced using the capped mash method. A majority of 7 tasters accurately chose the cup containing the capped mash beer, while only 3 made the wrong selection. However, nearly all of those who made the proper selection said it had little do with astringency differences, which was not overtly noted by anyone, but rather the full mash beer was described as being “more flavorful, fuller flavor, less watery.” Interesting.

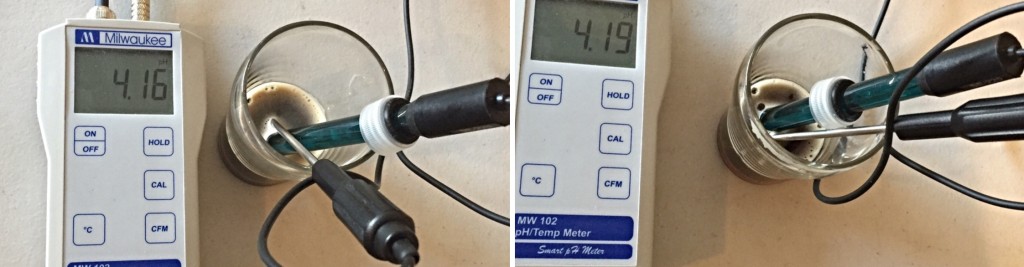

My Impressions: In 4 semi-blind triangle tests, I was able to accurately select the odd-beer-out three times, which meets my own private reliability standards. I experienced the full mash beer as being fuller in flavor and mouthfeel with a more rounded overall Stout character, while the capped mash beer actually came across to me as more astringent. Weird, I know, especially since I wasn’t the only one who experienced them this way. Curious what might be causing this perceived difference, I took a pH readings of the finished beers, fully expecting to see a difference similar to that observed when measuring the mash pH. I poured off small amounts of each beer and let them warm to 65˚F before proceeding.

Imagine my surprise when the full mash beer clocked in just .03 pH lower than the capped mash beer, within what I’d guess is a reasonable margin of error. Maybe this is to be expected, I’ve no clue and I’m nowhere near smart enough to understand how this happens, but at the very least it tells me any perceived differences likely weren’t a function of pH.

| DISCUSSION |

I trust (hope) I’m not the only one who feels uncomfortable settling on any conclusions based on a single point of data, particularly given the fact 1 response could have swayed the outcome. Either way, based on my biased experience and the results from this xBmt, I’m compelled to accept the capping the mash method may not necessarily have the impact I previously thought. Since I preferred the full mash beer, that’s what I’ll be sticking with for now, not because I think it’ll have some drastic impact on the quality of my beers, but mostly because it’s simpler. As with most of these xBmts, especially the first iterations, much more investigation is required in order to make any solid determinations, something I absolutely look forward to doing.

If you’ve messed around with different methods for using roasted grains, I’d love to hear what your experience has been like, please share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

46 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Roasted Grains: Full Mash vs. Capped At Vorlauf In A Dry Irish Stout”

Nicely done. Really enjoy your experiments.

I have recently read Gordon’s Modern Homebrew Recipes and in the book he adds crystal and roast malts at Vorlauf for all the recipes. I had been wondering whether I should change to do the same. Its good to see that it appears to be fine to add during the full mash as its better for my Mash PH to do this.

I think it depends on what you’re going for. If you’re brewing a beer that Gordon will be judging, I trust he’d pick up the difference and it sounds like he prefers adding roasted grains later, you might consider capping 🙂

I just kegged a beer, 1.062, 1 lb. C40, .5 lb chocolate and 1 lb. black patent. No astringency.

What was the O.G. of both batches?

1.039

I’ve never done anything special with roasted grains. Always full mash, and I haven’t experienced any significant acrid or astringent qualities in the finished beer. When using roasted malts, I think grist composition and proper mash out temps do more to hold off acridity/astringency than the length of mashing the roasted malts. Just my opinion.

Interesting xBmt nonetheless. I’ve always looked at guys on the other side of the fence that were cold steeping or partial mashing their roasts and wondered if I was missing something.

It would be interesting to see another iteration of this xBmt using cold steeping vs capping (or full mash) as the previous commentator mentions this being the other option often used with roasted grains

A bit off subject, but lately I can’t seem to read the full article through the WordPress app. I end up backing out and doing a Google search. Just thought I’d mention that in case anyone else is experiencing the same difficulty. Just tried a “capped” oatmeal stout myself, not quite so eager for it now… Cheers and thanks.

Hmm. I did recently migrate off of the WordPress servers and onto a new one, perhaps that caused the issue. Either way, if you follow Brülosophy (see top-right corner of page), you will get an email every time we publish that you can click to read the whole article. Sorry about the inconvenience!

It will happen!

Really interesting experiment!

I’d be interested to know what difference that mash pH had on the results – almost all the sources I’ve ever seen say that 5.1 to 5.5 is an ideal range, and many say that below 5.3 is best avoided. Perhaps a difference in enzyme efficiencies might account for a difference in body and mouthfeel?

I’ve read the same thing. Not really sure how to explain the results, definitely interested in hearing from someone smarter than me 🙂

Beta amylase is supposed to actually have an ideal pH range higher then the “ideal mash pH” as a whole. The range of say 5.1-5.4 is a compromise to best select the most benefit of multiple factors. But if you look up the ideal pH optima” of beta (try Kai Troester’s page brewkaiser.com, or any malting/ mashing science texts – Bamforth, Lewis, etc) it’s aroung 5.8 IIRC – thu the higher pH MAY (in some settings, in some systems, with some malts ….blah blah) convert to a more fermentable and thinner wort.

Scientific Principles of Malting and Brewing (C. Bamforth)

I think the “great” Gordon just has his shtick/unfounded fear of “harshness” from roasted malts and so every recipe has to have the specialty malts added at the end of the mash. I’ve used up to 30% black malt and don’t get harsh or acrid flavors. I think it’s fine if you want to do it but you will have to add more of the specialty malts to get the same flavor if you are following a standard recipe. If you are getting “harsh” flavors in your homebrew I would look at water chemistry and pH before blaming the malt…

Since tannin extraction is also a factor of solubility due to various pH (higher = more can dissolve into and stay in the wort) then I agree. If you properly control pH you potentially can have a black beer with subtle non acrid smooth roast – schwarzbier.

I will say Gordon method does have one major benefit – not needing to dick with pH in the mash – per se. If you always have the same water and about the same base malt then your pH should be about the same so the results are fairly consistent from beer to beer. Then you had minerals if desired for their flavor impact. I like that he gave brewers another way vs blindly following convention. Now brewers have more choices. Try various methods, sample, share, take notes, learn, adjust.

A year or so ago there was an interview with Gordon about this technique and I recall he essentially said what you’re saying – it takes out the pH variable. His reasoning was that the whole exercise of adjusting ph for dark malts complicates the process, risks off flavor extraction, and has minimal benefit to the final beer. I am pretty sure in that interview he was recommending steeping the dark grains.

DrW,

During his presentation at NHC a few years ago, when the book was released, he did talk about the benefit of simplifying or eliminating the pH adjustments.

“His reasoning was that the whole exercise of adjusting ph for dark malts complicates the process, risks off flavor extraction, and has minimal benefit to the final beer.”

Not sure I agree with that bit. Is that a quote or a paraphrase? The higher risk, IMO and per the reading vs controlled experiments, is that higher pH is the problem. Higher pH may actually be better for efficiency but you risk tannin extraction, and if the high pH carries over to the final beer then it may have a duller flavor.

Most people have moderate to high carbonate water and thus with most pale malts, with common tap water, your mash pH will tend to be slightly high (5.7-5.9 vs. the recommended 5.2-5.6 ish). Adding some darker malts benefits the average person for mash pH. So if you exclude it and adjust – theoretically if it takes 3 ml of lactic at your house then you can always use that or close to it – you don’t need to change your adjustment every single time you change the malt bill for each and every new beer and grist.

For what it’s worth, it seems like your results in final beer pH are exactly what you’d expect given your mash pHs. The difference in H+ concentration between a 4.16 and a 4.19 pH is is right around 5×10^-6 and betwen 5.0 and 5.3 it’s right around 4.6*10^-6. So the difference during the mash and after fermentation in the measured hydronium concentration was very close to the same and probably these two values are within the margins of error for the device…

Plus, there isn’t a defined drop for each yeast every time. They’re living organisms and they attempt to loosely regulate their environment for optimal conditions. Just as out body hair stiffens and blood flow is altered for a range of temperatures, yeast act as ion pumps (H+) – not necessarily for the same reason or in the same way.

Brulosopher, on the beers you received the astringent feedback from your scoresheets, did you log the pH for those? My experience tells me the harshness Gordon speaks if is wholly dependent on water chemistry, and not “to some degree,” so I am wondering if your pH was low on those batches also. The ideal coffee water temperature is often stated as between 195-205, so I can’t see how a mash temp of 150F-160F would be an issue. I personally also struggled with this acrid problem in my dark beers, and I noticed your salts under MISC are only CaCL and CaSO4, neither of which can really offset the acidity. I know you’re not testing for this, so perhaps this was intentional. But FWIW, I really started having success with my dark beers when I started adding pickling lime to the mash (with the dark grains in it) to raise the pH to my target while still allowing for full extraction of the roasty flavors.

I don’t have the pH readings logged for the Dry Stout I entered in the comp, but it was the same recipe as this one with more MO in place of the Rye. I measured the pH of both batches during the mash as well as once they were finished, pics are in the article.

Never heard of this technique, but it sounds very interesting. How was the beer overall? I’m in the mood for a stout and love rye. Might be my next beer.

This is a technique I have been using lately, so this xbmt really peaked my interest. I actually won an award using this method on my last dunkelweizen, and have used it since.

But, do you think that the outcome of the taste tests would have been different if the capped mash and the not capped mash were both adjusted to the same pH?

Granted – the capped mash pH might change at vorlauf when the dark grains added, but by then all the conversion would be complete….

Outcome in terms of general distinguishability or regarding beer preference? I’m not sure either way, but you know I plan to test it out 🙂

Either / or. What I’m unconvinced about is whether the differences that the testers perceived were down to mash pH rather than the variable being tested. But please, test it out! I like the capping method because my water additions only need to be calculated for a grain bill consisting of 100% base malt, so it’s a convenient way to keep things simple.

Ahh, I think I see what you’re saying. We absolutely have mash pH xBmts on the list, given Malcolm’s and my interest, one of us will likely get to it sooner than later.

I’m interest to see how this result might change in a something like a pale ale. Reason being that I feel like a stronger beer might allow for more noticeable differences on the flavor/feel of the beer.

What comes to mind is this:

Having different pH during mash, regardless of the final beer pH, is important in many aspects. pH influences the saccharification enzymes which could be a part of the reason for the difference in FG in the beers, if we exclude a mistake during FG measurement. Of course a thermometer with a bigger uncertainty of measurement(>0.5C) could contribute some error as well. pH during mashout alters the extraction of tannins, theoretically.

I would try to control the pH during the mash, controlling the water. It’s important and a bit difficult (but not impossible) to get the same pH during mash but also to get the same water profile in both brews.

So I would try this experiment again taking more pH readings so as to get more data to work on with, for example for both brews I would measure pH

start of mash

before and after the addition of roasted barley

during mash out

before and after boil

final beer ph (which you measured)

And of course I would have the water analysis + mineral additions in hand.

Sounds like you’ve got it all figured out. I look forward to reading your results.

I agree with this….

I would be interested in seeing the results while shooting for the same mash pH. Distilled or RO water could be used to get a “blank slate”, then add the same amount of gypsum and CaCl2 to both mashes, then add Baking Soda to adjust the pH of the full mash accordingly. I think that would give a better representation of the effect on taste from late roast additions.

Either way, very interesting, and thanks for the time and effort put into this!

The only time I’ve really had a problem with astringency was when I got a stuck sparge with a Foreign Extra Stout. I had a pound of roasted barley and a quarter pound of black patent, and my runoff took forever. I’ve brewed the exact same recipe 4 other times and never had a problem, so I think the contact time was to blame. I normally do a 1 hour mash at 154.

I would be curious if there is an effect with traditional sparging techniques (ie mash out and sparging with 170 F water).

I’ve read a couple of places that, long story short, yeast does an incredible job of bringing the pH in a narrow range in the finished beer regardless of mash pH. I’m not really sure but that would be my guess.

Great one! The results were quite interesting. Would you consider using the capping method for say maybe a Black IPA or dark saison?

If ever I were to make a Black IPA or Dark Saison, I’d probably use Midnight Wheat or Blackprinz in the full mash, though if my only options were something like Roasted Barley, sure, capped mash would likely be my next choice.

This is a test.

1) I just read Strong’s chapter on this subject last night so this was perfect timing to see the results in a live setting. If I’m not mistaken, he also mentioned cold steeping the roasted grains and adding the liquid to the kettle pre-boil as another method. Any chance we could get another take at Strong’s theories with this as a variable?

2) I’m seriously considering the Brew Bag as an added filtration liner in my mash tun like shown in your photos. Since implementing the bag into your brew system, have you noticed any changes to your brewhouse efficiency?

1. But of course!

2. Not really. I ended up getting more sweet wort from the run with the bag, so I adjusted for that and all is back to normal. Even before that, it was a negligible difference.

Maybe the higher mash pH lead to more tannin extraction in the caped mash? The end resulting pH is likely more to do with fermentation than starting pH of the mash. It’s the astringency of the tannins you probably taste not the acidity.

I tried cold steeping based on Strong’s book, but I didn’t appreciate any improvement on the flavor of my beer when I did. Ice gone back to regular mashing.

Chris

It’s really difficult to appreciate differences brew to brew especially separated by time – more so if they are subtle.

I have used Gordon’s method for my last few brews since reading Modern Homebrew Recipes with full boil BIAB batches and add the capped grains as I heat to mash out. One of the things he mention in that book, is that he adjusts his brewing water prior to the mash, by using RO water and adjusting with 1/4 teaspoon of phosphoric acid per every 5 gallons of brewing water to get a pH of 5.5 before the mash. Then he adds calcium chloride and/or gypsum to the base malt mash.

It appears in your experiment you started with the same water for both and added the same water agents to both, is that correct? Would be interesting to see the experiment run again with the capped batch having the water adjusted per-mash as per his book, then normal and then see if there is any perceived difference in the taste tests.

It’s on the list!

You are the best! Striking all myths. Thank you!

I am interested with coffee if it makes a difference to cold brew it in the last 15 minutes of the boil or put it in the fermenters

The one thing that always gets me about this method is that pro brewers don’t do this, and they turn out some damn fine beer. I really feel it’s all about pH, not contact time. I loved the xBMT though, as I was considering trying mash capping on my next batch, just to see how it goes. Maybe not now.