Author: Matt Del Fiacco

Every now and then, I’m blown away by the results of an xBmt, particularly certain non-significant ones that leave me instinctually searching for reasons as to why the results turned out the way they did. Based on reader comments, it’s clear I’m not alone, with one of the more common posited explanations having to do with the fact the xBmts focus on single variables in isolation and that perhaps compounding certain variables would create greater differences. Two beers fermented at different temperatures with all else being equal might be too similar to tell apart, but what if the beers were also treated differently in other ways?

I refer to this as the “best practices are insurance” approach and it’s something I openly admit to still following. However, the reportedly positive results of the multiple short & shoddy brew days completed by other contributors, along with some of the surprisingly non-significant xBmt results, led me to question whether this insurance was perhaps illusory, that my adherence to traditionally prescribed methodology was more for me than the beer I was making.

As much as I enjoy brewing, I don’t always have time to squeeze a full brew day in due to how long certain parts of the process can take. If I were able to keep my pipeline flowing by cutting certain corners that would reduce my brew day to a fraction of the time it currently takes, I’d definitely be interested, but only with no sacrifice to the quality of the beer I was making. I finally took it upon myself to see just what this short & shoddy business is all about by putting it up against a beer made using my standard process.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer made using an abbreviated mash and boil that was under-pitched then fermented warm and a beer made using a more traditional brewing method.

| METHODS |

I thought it’d be best to brew a clean and simple recipe so that any differences between the beers were easily identifiable.

Wrong Way’s Right Blonde Ale

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 23.9 IBUs | 4.7 SRM | 1.045 | 1.011 | 4.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.045 | 1.01 | 4.6 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Ale Malt (Rahr) | 9 lbs | 96 |

| Carafoam (Weyermann) | 6 oz | 4 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemondrop | 23 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 6 |

| Lemondrop | 47 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 6 |

| Lemondrop | 62 g | 1 min | Boil | Pellet | 6 |

| Lemondrop | 62 g | 3 days | Dry Hop | Pellet | 6 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Ale (1056) | Wyeast Labs | 75% | 60°F - 72°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Yellow Malty from Bru’n Water Spreadsheet |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a starter of Wyeast 1056 American Ale yeast a couple days beforehand that would be pitched only into the traditional batch. The next morning, I began by heating RO water for a full-volume no sparge batch, adjusting it to my mineral profile, one adjusted appropriately for the shorter boil.

I weighed out and milled the grains as the water was heating.

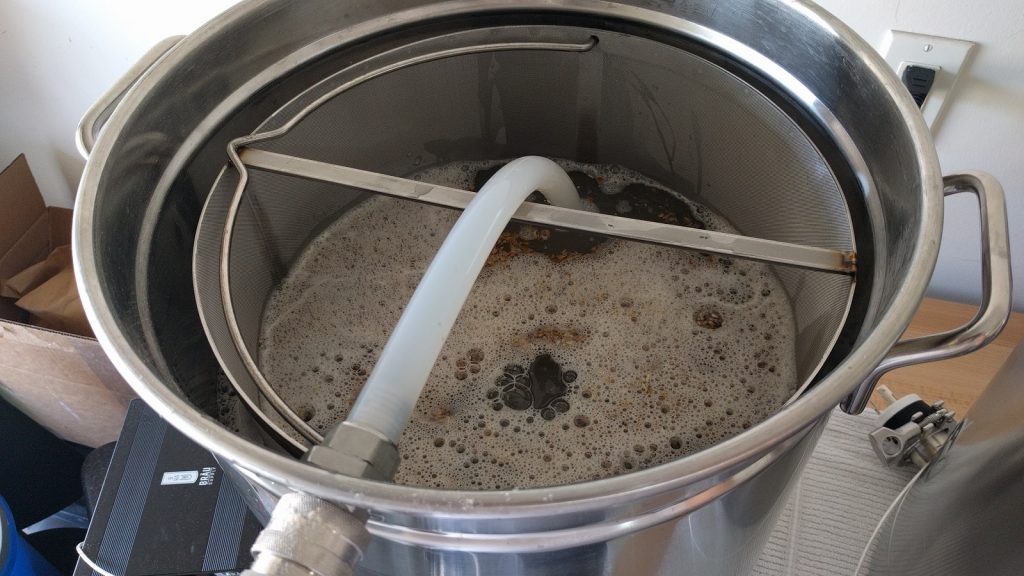

Once the water reached strike temperature, I set the controller for the traditional batch to my desired mash temperature, added the grist filled basket to the water, and gave the mash a gentle stir to ensure there were no dough-balls before turning the recirculation pump on. In order to reduce the potential influence of extraneous variables, I let the short & shoddy strike water sit without grains at strike temperature until the traditional mash had been resting for 30 minutes, at which point I mashed in.

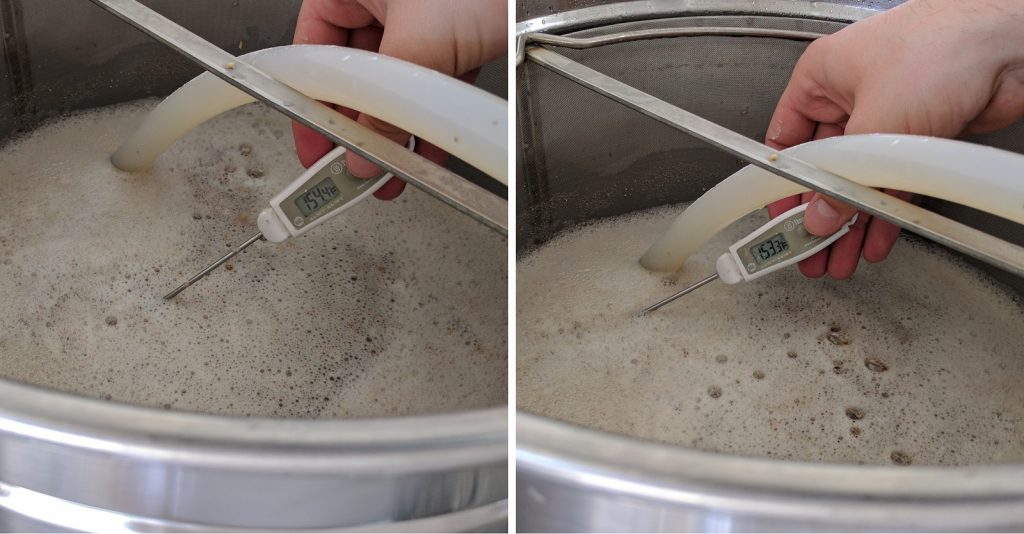

The traditional mash stabilized at 154°F/68°C, my intended mash temp, and the short & shoddy mash initially settled at 153°F/67°C, so I adjusted the controller to bring it up to the same 154°F/68°C. This took about 7 minutes.

Each wort was continuously recirculated and about 15 minutes into each rest, I grabbed small samples for a pH measurements that showed I’d hit my targets.

I weighed out my hop additions during the remaining 15 minutes of the mash.

Once the mashes were finished, I removed the grain baskets, set them over the kettle to drain, then brought the remaining wort to a rolling boil.

The traditional batch received its first dose of hops 40 minutes into the 60 minute boil while the first hop addition was made to the short & shoddy 10 minutes into the 30 minute boil; all subsequent hop additions were made at the same points within the final 20 minutes of either boil. When each boil was complete, I quickly chilled the worts and took hydrometer measurements showing they’d both achieved a similar OG.

I split the wort between two fermentation kegs that were placed in separate chambers. While the traditional batch had the temperature probe insulated against the keg, the probe for the short & shoddy batch was attached with some electrical tape to the inside of the chamber.

Once the traditional wort was down to 64°F/18°C, I pitched the yeast starter and set the chamber to my desired 66°F/19°C fermentation temperature. The short & shoddy batch was pitched with a single fresh pack of the same yeast, no starter, then left to ferment at ambient temperature of 72°F/22°C.

I noticed fermentation activity in the traditional batch kick off several hours before the short & shoddy batch, though both were bubbling away within 16 hours of yeast pitch. After 10 days of activity, signs of fermentation had diminished and I took hydrometer measurements showing both beers had attenuated to the same FG.

Dry hop charges were added to both batches at this time and they were left alone for 48 hours before I proceeded with cold crashing, fining with gelatin, and transferring to serving kegs.

I burst carbonated both beers overnight then reduced the CO2 to serving pressure and left them alone a few more days before I began serving to blind participants.

| RESULTS |

In total, 22 ABNormal Brewers club members with varying levels of experience, all blind to the variable, were served 1 sample of the beer made using traditional methods and 2 samples of the beer made using short & shoddy methods, then instructed to select the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to select the dosed sample to reach statistical significance, a total of 13 (p=0.012) identified the odd-beer-out, suggesting participants were indeed able to reliably distinguish a beer made with traditional methods from one made with an abbreviated mash and boil that was under-pitched and fermented warm.

The 13 participants who correctly selected the unique sample in the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief set of additional questions comparing only the two different beers, still blind to the nature of the xBmt. Likely aligning with the expectations of many, 6 tasters chose the traditional beer as their most preferred while only 2 reported liking the short & shoddy beer more. Equally as interesting is the fact 4 tasters reported having no preference despite perceiving a difference between the beers. Only 1 lone participant said they experienced no difference between the beers.

My Impressions: Based on the initial similarities in gravity and wort color, I wasn’t so sure I was going to be able to tell these beers apart in semi-blind triangle attempts. Out of 3 attempts, I selected the unique sample twice, obviously not perfect. I perceived the traditionally brewed batch as having a generally cleaner flavor profile with a crisp finish while the short & shoddy batch was a bit less defined and seemed to leave a lingering aftertaste in my mouth. Overall, I’m really happy with both beers, and based on aroma alone I cant tell them apart at all. In blind triangles, I got this correct 2/3 times. I’m startled by how similar they are.

| DISCUSSION |

The triangle test is an elegant method for determining whether people can reliably distinguish a difference between beers, providing us some information as to whether a particular variable or set of variables has a noticeable impact. In the case of this xBmt, participants were indeed capable of reliably distinguishing a beer made using traditional methods from one made using short & shoddy methods. However, a major downside to the triangle test is that it tells us very little about the degree of difference perceived by tasters between samples, only that the they were disparate enough for people to tell them apart at a statistically significant level.

It’s not sound to make extrapolations based how many tasters more or less than the significance threshold identified the unique sample, and we’re not going to do that here, which leaves us with only the anecdotal reports of correct participants and the perceptions of yours truly. Despite a plurality of participants endorsing the traditional beer as most preferred, not a single one described the short & shoddy beer using terms that would indicate anything was wrong with it. Moreover, I was shocked at just how similar these beers were, even though I was able to tell them apart 2 out of 3 times. I felt both were solid examples of the style with no noticeable off-flavors, which blows my mind.

Considering the objectively observable similarities between both beers, I’m left asking– just what is responsible for the difference? Maybe it’s true what many have speculated, that while mash length, boil duration, pitch rate, and fermentation temperature on their own may not have a perceptible impact, combining these “shoddy” practices does. Ultimately though, I was happy with both beers, and I’ll have no problem shortening my brew day now and then to keep my pipeline rolling.

If you have thoughts about this xBmt, please share them in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support Us page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

43 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Traditional vs. Short & Shoddy Brewing Process In A Blonde Ale”

I´d like to see this exbeeriment excluding the fermentation variable.

Same! Definitely on my list. I’ll be doing short mashes and boils in the future, without a doubt.

Me too. I wonder if there would be any perceivable difference in the two had the fermentation schedules been the same. Most of my issues with brewing have to do with how long the brew day takes and once I get it in the fermentation chamber it’s smooth sailing till keg day.

Thats my exact exbeeriment that I keep asking for!

My thoughts exactly! US-05 in both at the same temp. I bet that shifts it to a non-significant result.

Yes, also this is a case where having people fill out a judging sheet might have given you more info as to what exactly worked better with the traditional VS short and shoddy. Even if it were just the descriptive sections of the form, it might point to what factors people felt were affected.

I did something like this in my last batch. 20 min mash, 20 min boil. Normal cooling, pitched a normal amount of yeast and fermented at a normal temp. I had terrible efficiency and the gravity is way lower then what I was targeting so my extra hoppy pale ale turned into a session IPA. But the beer tastes great! No major flavor faults from the short mash / boil

Very interesting, and surprising. To clarify, did you pitch at 64 for the shoddy batch as well or did you pitch at 72?

Pitched at 72 for the shoddy batch, great clarification!

I do short mash, and short boil all the time, on fruit beers and big super hoppy IPAs. Yesterday, I mashed till the mash was done (45 minutes), and boiled for 45 minutes. I think the real key is knowing where you can cut corners to have a quick brew day.

I’ve also experimented with the other end of the spectrum, mashing overnight and finishing up in the morning. I think it makes the brew day feel much shorter splitting it up. The most recent issue of Zymurgy had a very interesting article describing another factor for a short brew day that I will definitely be trying… essentially short notice shoddy mash and boil but fermenting in and packaging from the same kettle. Almost no cleanup!

That’s me Lucas. Let me know if you have any questions. My experiences are documented at http://www.onepotbrewing.com. Many of the time-saving techniques were based on these “short and shoddy” experiments. I also don’t do starters, and I do think that’s what made this experiment significant. This article makes sense to me: I don’t think I brew world class beer with my system, but it’s good enough for me (and my standards are higher than most).

That’s awesome Matt! I’ll check out the link

Honestly, my biggest time saver was stepping up and buying the hydra wort chiller. I used to wait almost an hour to chill my beer, now it takes 10 minutes or less. This, combined with batch sparging and cleaning my equipment during the boil has shortened my brew days to 3-3.5 hours, not too shabby. Definitely short enough that I don’t really feel the need to cut corners, if anything, the 1 hour boil gives me time to clean shit haha.

I have a regular chiller and I only chill for 10 minutes tops, which usually brings me down to 80 or so. I stir a lot while chilling, which makes a yuge difference. I think partial chilling (i.e. chill to 100 and let a freezer do the rest) is a big time saver, although I understand people could be squeamish on that.

As long as your mash pH is within range, beta/alpha amylase conversion should be done within 15 minutes.

What pH do you recommend to optimize both?

5.3 to 5.5

Figured that. I’ve been mashing with a higher pH than used to now to try and get good activity from both. I’ve been going 5.4-5.5, have even done 5.6 with good results.

Iteresting you should say that. I’ve heard that is the theory, but I don’t believe it in practice. Have you actually measured your conversion over time over several brews? I’ve done this over about 15 brews of various types and OGs, all using a Grainfather, measuring with a refractometer every 10 minutes. At 15 minutes, on average, I get about 45%. It takes me about 45m to reach about 95%, but I always get more conversion going to 60m, sometimes going on beyond that to 90m. My curves are remarkably consistent, so in my setup I’d never go less than about 50m before draining and sparging. What this does not measure is any additional conversion that takes place during draining and sparging; if this process starts at 45m, and you get an extra 15 min of workable mash temps (not doing a mash-out), then you may well end up with an almost complete conversion anyway.

I have a question about your brew setup. Have you noticed any increase in mash efficiency using the no sparge with continuous wort re-circulation vs no sparge without re-circulation or traditional batch sparge? I use the no sparge technique to save time but was considering adding a pump to re-circulate wort to burst efficiency. Thoughts?

I get decent efficiency with no sparge, 68-72% depending on OG, and I don’t recirculate. I’m not nearly concerned with efficiency as I am consistency, so I’ve not really gone out of my way to increase it.

I don’t question your results; however, I think that you would find many more significant results if you changed your methodology. My hypothesis is that some among us would pick the odd beer out time and time again while others would not in the majority of these experiments (and my argument is not the experienced beer drinker vs. amateur argument, which I agree probably doesn’t matter.)

My father in law, for example can taste a single leaf of cilantro in a pot of soup. There is also a famous experiment called the lady tasting tea that I would cite. Therefore, the question us not whether or not the beer tastes different to a random person, but instead what percentage of the population can detect the difference.

You suggest we game the xBmt processes so we can elicit significant findings more often?

-Or –

We should configure a super panel of elite tasters, such as the one person you mentioned, that is also of an appreciable size and ever on the ready?

I told Marshall that’s what we should do! In the meantime, I am fine with using the average palate because I am an average everyday normal guys, and so are the people who drink my beer.

Not saying either of those. I’m not ridiculing your process, as I said, I think you have shown that most people can’t detect many things. However, I would like to know if there are some people who can consistently taste the differences and if so what percent of the population it is. I’m not sure why you are trying to straw man my question as this isnt “gaming” anything but instead just asking a different question. It also doesn’t require any super elite tasters, but just giving the same set of people the test multiple times to see who can consistently get it right. As you guys have pointed out on comments, sometimes you can consistently pick out the odd beer even in the tests where the result was non-significant.

Well, I teasing.

But when you suggested altering processes, I would consider changing the processes as a way to p-hack. If we get a result outside of expectations, then alter the process of making the beer, or measuring/ analysing results, that is a form p -hacking. That is all.

I too would love to compile results based upon people who are seemingly “great tasters” purely for the fun of the exercise, it’s just not practical.

Further, I’ve found people’s abilities often don’t cover many variables over a full spectrum. – one person is good at this -sometimes, and another at that… etc.

I think we can seemingly more often than not tell the beer apart because we are sighted to the variable, know the beer intimately (have seen and tasted along the way), and have multiple chances at it so we have honed in on what to look for.

I know I bang on about this but there is nothing wrong with using a detection apparatus with sufficient resolution to actually detect the variable in question. It is NOT cheating it is just normal science. If I used a piece of lab equipment that could not dectect a variable present in tiny amounts then I would be wasting time and money. I think the one thing you have proven time and again is that the average beer drinker can’t taste very small differences in a triangles test, regardless of what the difference is. I really think it’s time to re-examine your tasting panel concept otherwise you are just (for the most part) wasting your time.

I’m not sure it is feasible but I think it would be interested to see the “batting average” of tasters picking the odd beer out who participate in multiple exBEERiments. It wouldn’t change the validity of the findings but could be an interesting tidbit

Yeah. I’d find it interesting as well. Anecdotally, it seem people are all about…. average. They are right sometimes, and wrong others. I only have about 2 people, based loosely on memory, that seemingly are right most of the time. They only stick out bc I known them and when they are incorrect it’s an oddity. That is unscientific, I know, but it’s also telling at least to a minor degree. 2 people out of a recurring pool of 30 or so. The other 20-30 are infrequent and/or one offs.

You guys are missing the point – all these “studies” can show is whether or not most people in a room could distinguish two similar yet varied beers. Brulosophy dudes have never tried to extrapolate beyond that

Great stuff. This xbmt stings a little bit. Why? Well because I’ve worked on each element of the traditional method until I had it down. I’m still constantly looking to improve my process. Now you do this and tell me its not that big of a deal.

So I ask, in each of your brewing educations rank what was taught to you as the most important part of your process? For me mash temp, boil duration, sanitation, fermentation temp and speed of wort chilling were first. Then followed by yeast handling (pitch rate, starter size, pitch temp), and finally pH and water. Ive noticed big changes in flavor with pH and water adjustments. But that was after all the other process were somewhat mastered.

Could it be that we have it all backwards? Should we be teaching water and pH first? IDK

I much prefer the single-variable experiments. Testing several at once inevitably raises more questions than can be answered. For instance, I’m not sure which of the shortcuts had most effect on the beer – mash time, boil time, pitch rate, fermentation temp? No point guessing. Also, somewhat disappointing result as it does suggest the long and tedious approach produces better beer…

Brulosophy: *isolates singl variables*

Comments: “You won’t get significant results unless you combine multiple variables”

Brulosophy: *tests multiple variables at once*

Comments: “You should test less variables at a time to see which ones are having the most impact.”

Perfect response ^ thank you for this!

Single variable experiments work fine. However, lumping together all the variables in a two-batch experiment doesn’t tell you anything besides “these two beers are a bit different”. You need a more complicated design to explore multiple variables, such as a factorial experiment. It’s true that people asked for multiple variables exbeeriments like the one done, but it was never a particularly smart suggestion.

You need a particular experimental design to explore several variables at once, eg a factorial experiment. I know lots of people suggested a test like the one carried out, but it was never a smart suggestion as the only conclusion you can draw is that the beers are a bit different for unknown reasons. In contrast, the single variable tests work well.

Apologies, posted twice as I thought first one got lost in the ether!

I love this multi-variable experiment. Thanks for doing it fellas.

I’m sure glad you guys do all this work. I don’t have the time or equipment to do the trials you can do, and your results give me the courage to try for myself and see what happens if I break the rules. So far, because of you, I’ve cut my brew time almost in half, I make better beer than ever, and I’ve saved a load of money. Thanks for that, and keep up the good work!

The only(?) fundamental flaw with this and other xbmts is lack of true replication. But until someone donates the time & $$$ to allow true replication… I’ll go with the flow and say thanks very much for the insight (which is more than we had before), and the great effort.

Another thing… it’s pointless talking about changing the methodology without first very carefully specifying the question. Asking if a sensitive chemical analyser can detect difference between brew methods is completely different to asking if everyday beer drinkers (whatever that means) can. The question comes first, then the experimental design & methods.

Oh, and p-hacking usually refers to practices that could alter the p-value for a given question. Once one changes the question, its not really p-hacking, I would say.

Hi,

been doring it short and shoody for the last 60 brews by BIAB, 60-75% efficay, overnight chilling in fermenter, mashing in oven, boil one hour, and I have fund that if you focus on pH of mash, fermtation temperatur and patience of storage you will get fine beers!

I also recon the fementation temperatur is to “blame” for the differency.

I say that good recipies and focus on temperatur and Water chemistry is way more supportive for good beers than BIAB or no-BIAB or mash.time and boil times. The 2 later will reflect on efficacy of sugars and bitterness, but that can be adjusted to you need and equipment!

Klaus

I did a variation of this yesterday. I did a full water volume brew in bag method. I did a 30 minute mash and 30 minute boil. I also added all hops as first wort additions. Unfortunately, my strike temp was high as was my initial mash (162F) but was quickly reduced to 156F. 2 hours start to finished brew day. My efficiency was terrible and the wort was 30% under my target 1.052 gravity. It is fermenting well with one vial of 001 and a vial of clarity ferm.