Author: Jake Huolihan

For many brewers, reducing the temperature of beer once fermentation is complete, a method referred to as cold crashing, is common practice. Colder temperatures encourage the flocculation of yeast and other particulates, making them heavy enough to drop out of solution, thus leading to improved clarity. When used in conjunction with fining agents such as gelatin, the effect is often enhanced, resulting in both higher yield and clearer beer in the package.

The simplest approach to cold crashing involves making a single adjustment to the controller such that the temperature of the beer is rapidly reduced. Critics of this approach contend that such quick chilling can “shock” yeast, potentially causing them to excrete compounds that lead to undesirable off-flavors. The solution involves reducing the temperature more gradually, 3-5°F/2-3°C per day until it reaches the desired point, which allows the yeast time to acclimate to the cooler environment.

I’ve not regularly cold-crashed in awhile, mostly due to fears of cold-side oxidation, but I’ve used both methods numerous times in the past and can’t say either led to notably bad beer. To better evaluate the impact cold crash speed has, I designed an xBmt to test it out for myself!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between beers where the cold occurred either immediately after fermentation or in a gradual manner.

| METHODS |

In hopes of allowing any subtle flavors caused by cold crash speed to shine through, I went with a simple Helles for this xBmt.

Climate Change

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 44.7 IBUs | 4.5 SRM | 1.053 | 1.016 | 4.8 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.015 | 5.0 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Odyssey Pilsner | 11.5 lbs | 96.84 |

| Carahell (Weyermann) | 4 oz | 2.11 |

| Melanoidin (Weyermann) | 2 oz | 1.05 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loral | 24 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.3 |

| Loral | 15 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 10.3 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest (L17) | Imperial Yeast | 72% | 50°F - 60°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 49 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 38 | Cl 61 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

The night before brewing, I weighed out the grains and collected the water in my kettle, adjusting it to my desired profile. After setting my controller to heat the water first thing the next morning, I milled the grain.

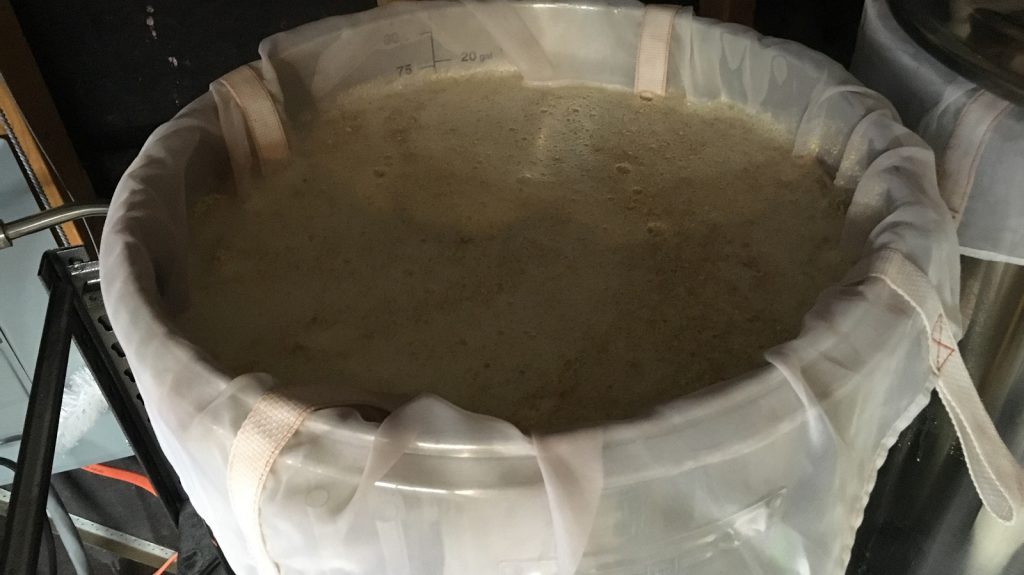

With the water appropriately heated, I stirred in the grist then checked to ensure it was at my target mash temperature.

The mash was left alone for 60 minutes.

With the mash rest complete, I transferred the sweet wort from the MLT to the kettle.

The wort was then boiled for 60 minutes with hops added as stated in the recipe.

Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort.

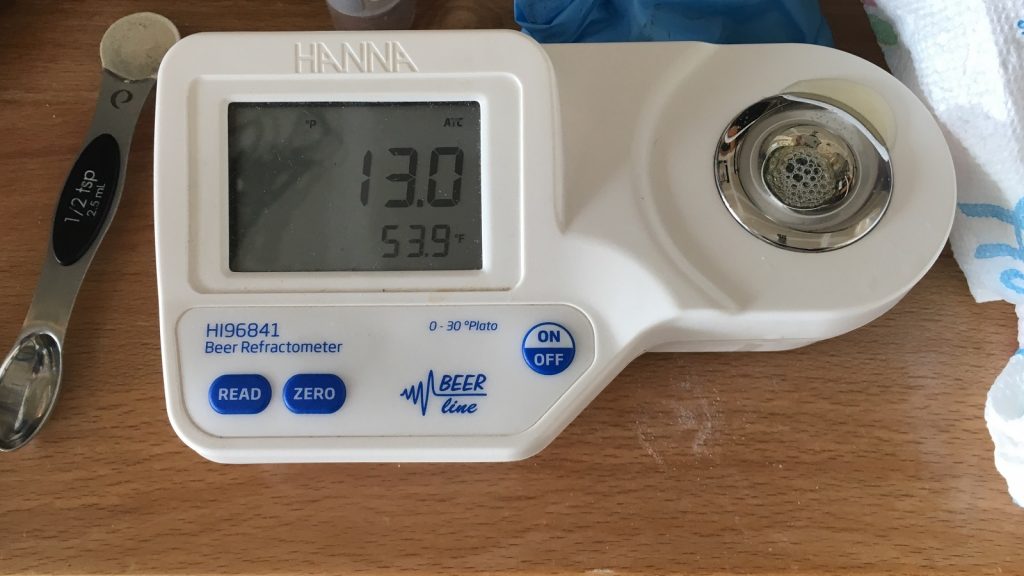

A refractometer reading showed the wort was right at my planned OG.

Identical volumes of wort were racked to separate sanitized Unitanks.

The filled vessels were connected to my glycol rig and left to finish chilling to my desired fermentation temperature of 50°F/10°C. This took about 15 minutes, at which point I direct pitched a pouch of Imperial Yeast L17 Harvest into each batch then hit both with a dose of pure oxygen.

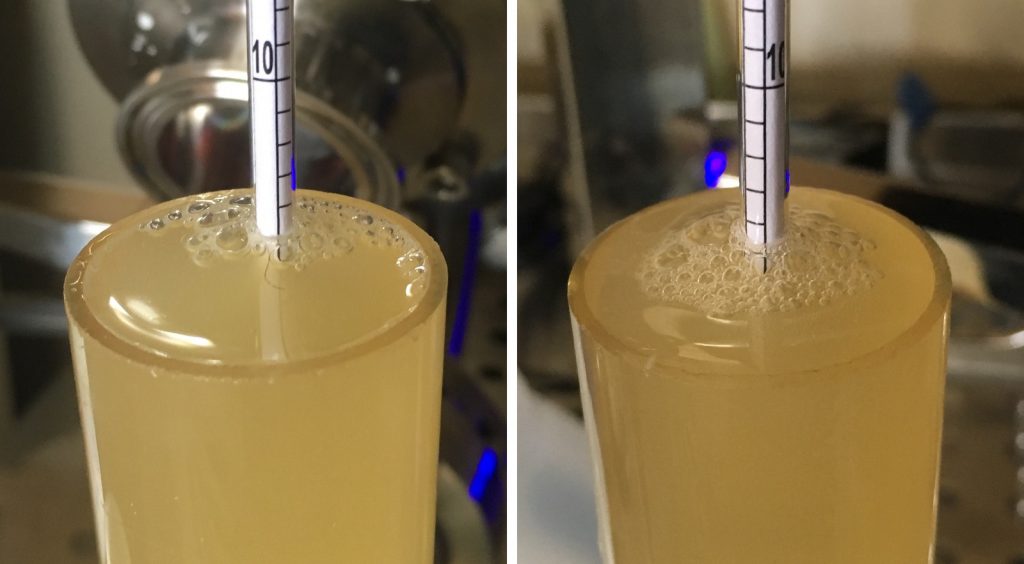

I observed decreased fermentation activity after 5 days, so I capped each Unitank and allowed each to pressurize to 10 psi. At this point, I also raised the temperature of the beers to 56°F/13°C for a diacetyl rest. The beers were left alone for another week to ensure fermentation was complete before introducing the variable. Hydrometer measurements at this point confirmed both had reached the same FG.

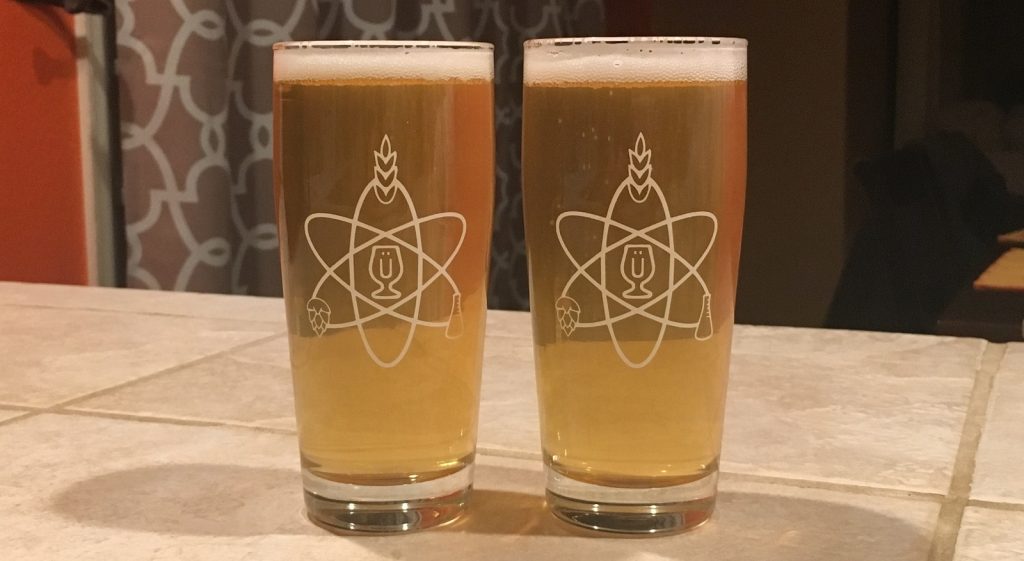

For one batch, I set the controller on my glycol chiller to 36°F/2°C to encourage a rapid reduction in temperature; the entire batch of beer stabilized at this lower temperature in just over an hour. For the other beer, I lowered the temperature just 1°F/0.5°C every 12 hours until it was at the same 36°F/2°C, a total of 10 days. The following day, I pressure transferred both beers to sanitized and CO2 purged kegs that were then placed in my keezer. Following burst carbonation and a period of conditioning, they were ready to serve to tasters.

| RESULTS |

Cheers to Denver’s CO-Brew Homebrewing Supplies for allowing me to collect data at their shop!

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 2 samples quick cold crash beer and 1 sample of the beer cold crashed gradually in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. While 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to accurately identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, only 5 (p=0.89) did, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a Helles cold crashed from 56°F/13°C to 36°F/2°F in 1 hour from one cold crashed gradually over a 10 day period.

My Impressions: Out of the 5 triangle tests I attempted, I happened to correctly guess the unique sample just 2 times. To my palate, the beers were identical, possessing the exact same rich, bready Helles flavor I know and love. This may quite possibly be the best Helles I’ve brewed to date.

| DISCUSSION |

For brewers who have a means of fermentation temperature control and want to package beer with little to no particulate, cold crashing is a no-brainer that will certainly cause yeast, hops, and other compounds to drop out of solution. The ideal time-frame to lower the beer temperature to just above freezing is up for debate, a common belief being that a gradual reduction will result in less yeast stress and thus a lower risk of off-flavor development. In contrast to these claims, tasters in this xBmt were unable to differentiate a Helles cold crashed from 56°F/13°C to 36°F/2°F in 1 hour from one cold crashed gradually over a 10 day period.

There’s no denying that yeast can emit compounds that contribute to undesirable off-flavors when under stress, and an environment that goes from warm to nearly freezing quickly is arguably more stressful than a more gradual reduction– consider the fable of the boiling frog. Similar to the truth behind this mythical tale, the results of this xBmt suggest that even when cold crashed faster than most homebrewers can reasonably achieve, the impact is minimal enough so as not to be perceptible.

I’ve long adhered to convention when it comes to cold crash speed and was fairly convinced the fast cold crash beer in this xBmt would have issues. The fact my experience with the beers aligned with the blind taster data left me with a sense of comfort that overshadowed my surprise. In the end, I definitely plan to decrease my cold crashing times in the future as a result of this xBmt.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

22 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Cold Crashing Speed: Immediate vs. Gradual In A Munich Helles”

I think the topic is really interesting since slow cold conditioning makes the whole brewing process a lot longer, which is annoying, so, well done! Two comments:

1) Supporters of the gradual process suggest to chill the beer as slow as 1 °C per day, which is two times slower than what has been done in this experiment.

2) Temperature shock is said to make yeast excrete lipids interfering with head retention: did you see any difference in that regard?

I would like to see this done on a beer like an IPA, which could show an effect of how the hops drop out and affects overall clarity. Otherwise, very well done! Thank you Brulosophy team for all you do!

Clarity should only depend on the final temperature though.

Great write up and thank for sharing the result. In your introduction you said “I’ve not regularly cold-crashed in awhile, mostly due to fears of cold-side oxidation”. Can you elaborate what method you are using to get the yeast to flocculate if you don’t cold crash?

The results are pretty much what I would have expected. A real and practical question arising from this experiment is, what is the impact on beer brewed using harvested yeast that has been either rapidly or slowly cold crashed. One would suppose that a slow crashed yeast would be more healthy due to less stress.

Thanks for the write up. I’ve been long interested in this aspect of finishing off beers, especially lagers. One question:

You noted “Following burst carbonation and a period of conditioning, they were ready to serve to tasters.” Could you elaborate on how long and at what temp the “period of conditioning” was done? This being a helles, and seemingly adhering to typical lager production methods, I expected to see an explicit lagering step.

Regarding this, I was under the impression that the temp shock that ensued after a rapid temp drop made the yeast less able to clean up during the lagering phase. However, if this wasn’t performed, then that could be a potential avenue of difference.

Just curious if the 44 IBU’s was a typo? Helles range is 16-22 unless you just prefer it higher. Great write up!

I live at 6k feet altitude, hop utilization is much lower than 100% which BS shows in my recipes.

Ah, That makes sense. I have made a Helles many times using Pils, Vienna and a splash of Munich 10. I should give this one a whirl and see how different it is. I love me some melanoidin malt.

My last handful of helles/pils have been omitting Vienna or Munich opting instead to go for a small charge of melanoidin as well as some cara for helles. I think I much prefer these though I really need to do one with 10% Vienna v not.

I don’t think the off flavors would come from “shocking” the yeast, but rather, if fermentation was not complete. I had a batch of Cal. common that had some diacetyl, but since it was bottle-conditioned, all that was needed was a week or two at room temperature to clean it up. Also made a nice bitter (kegged) with 1469 that had a slightly fruity taste when it was “ready”, but the taste dissipated gradually over a month. I store at cellar temp (56-60F).

Great experiment. With your fermenters and process you were able to single out the rate of temp change as the only variable, but for many brewers who can’t pressurize their fermenters, oxygen ingress may also be an important secondary effect of a quick cold crash. I’d be interested to see a similar experiment done with carboy and airlock, to see if a quick cold crash leads to increased suckback/oxygen ingress and a noticeable difference in a triangle test.

Keep up the good work!

Why do you suppose there’d be more oxygen suckback in a faster cold crash? I would think the volume of suckback a function of temperature, not time. Time is not a player in the gas pressure-temp-volume relationship, right?

Lee, totally agree, the expansion/contraction of the fluids in the fermenter is going to be dictated by the factors you mention (and not time). If start and end temperatures are the same, volume change and suckback volume during cold crash should be the same regardless of duration. However, one observation I’ve made is that some degree of gas production (assume CO2 production at tail-end of fermentation?) continues into my lagering phase. My hope with a slow cold crash is that this off-gassing from the beer is offsetting at least some of the pressure drop that would otherwise be occuring. If this is true, and if slowing down the cold crash can maintain a (more) positive pressure, I imagine less outside air and oxygen moving into my fermenters.

May be a totally bunk theory, but I like it. I know there are other factors at play, including temperature effects on solubility of gasses in the beer, etc. And for argument’s sake, let’s ignore the fact that if I bottle my beer and probably introduce waaaaaaaaaay more oxygen at that step anyways…

Did you do a yeast dump prior to cold crashing since you are using conicals? I currently use brew buckets so all the yeast that has previously settled out is still present. Do you think this could possibly play a bigger role? I am thinking about changing my process to pressure transfer from the brew bucket into a corny after primary fermentation so that I can pressurize the keg prior to cold crashing to prevent any oxygen from entering my brew as well not cold crashing onto a full yeast cake.

I did not dump the cone. What you described is what I do in every batch I make in brew buckets, and most in unitanks. Only difference with the unis is that I can cap fermentation, chill to drop stuff and then keg off the top of it.

Oh awesome. What do you pressurize your cornys to before cold crashing? I am going to try that method next batch.

What are the common off-flavors people perceive that are attributed to cold-crashing? I recently brewed a Pale Ale fermented with Imperial Loki at ~90F and then cold-crashed. I haven’t tried it in a few days but it definitely has some off-flavors I would describe as sulfurous/plastic. I wonder if that big of a temperature swing (~90F to 42F) could be enough of a shock to the yeast to produce those off-flavors.

As far as I know, too rapid temperature drops by themselves are associated with stale off-flavors and excessive ester production. However, cold crashing too early will not let the yeast do whatever it was doing at the time, so the temperature drop can simply make existing fermentation problems more evident.

How did the process take 10 days if you were dropping 2F every 12 hours (4F/day)? Looks like you only had about 20F to drop, so should have been 5 days, right?

My bad the wording should have been 2F every 24 hours (1F every 12 hours) for a total of 10 days.