Author: Phil Rusher

One of the four principle ingredients in beer, yeast are single cell eukaryotic organisms whose main task is biochemically transmogrifying wort into beer. Simply put—brewers make wort, yeast makes beer. Given its importance, brewers go to great lengths to ensure the best conditions for yeast so they can do their job and get out of the way. A common method brewers use to facilitate the acclimation of yeast to their environments involves increasing the number of healthy cells through propagation in a starter prior to pitching.

For the most part, making a yeast starter involves pitching yeast into a relatively small volume of un-hopped, low gravity wort, factors that are said to keep stressors negligible while allowing the yeast to healthily replicate. As effective as this method is, it does add extra steps to the brewing process, which has led some to rely on the arguably simpler approach of reusing yeast that previously fermented another batch, oftentimes by racking fresh wort onto an entire yeast cake. One potential issue discussed about this method is that it can easily result in overpitching, hence it’s often recommended the initial beer be lower in alcohol and have reduced bitterness to reduce yeast stress.

Despite the results of a previous xBmt showing participants could distinguish a pale lager fermented on a German Leichtbier yeast cake from one pitched with a starter, I was curious how a more characterful beer would turn out when racked onto a yeast cake that previously fermented a batch of dark, hoppy, higher alcohol beer and put it to the test!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a California Common fermented with a properly sized yeast starter and one fermented on a yeast cake previously used to ferment an Imperial Brown Ale.

| METHODS |

Wanting to test the idea that fermenting a fairly standard ABV/IBU/SRM beer using a yeast cake from a darker, higher IBU, and high gravity beer would affect the new, more moderate beer, I used the yeast cake from an Imperial Brown Ale.

Hanging Chad

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.7 gal | 60 min | 32.2 IBUs | 10.0 SRM | 1.052 | 1.012 | 5.3 % |

| Actuals | 1.052 | 1.008 | 5.8 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mecca Grade Lamonta: Pale American Barley Malt | 8 lbs | 69.34 |

| Mecca Grade Metolius: Munich-style Barley Malt | 3 lbs | 26 |

| Mecca Grade Opal 44: Toasted Toffee Barley Malt | 8 oz | 4.33 |

| Black Malt - 2-Row (Briess) | 0.6 oz | 0.33 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brewer | 15 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.4 |

| Northern Brewer | 20 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.4 |

| Northern Brewer | 30 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 7.4 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cablecar (L05) | Imperial Yeast | 73% | 55°F - 65°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 50 | Mg 0 | Na 15 | SO4 75 | Cl 63 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

I made a starter of Imperial Yeast L05 Cablecar a few days ahead of time.

Prior to brewing, I kegged a batch of Double Down Imperial Brown Ale that I’d made a few weeks earlier, leaving the yeast cake in the fermenter and storing it in my chamber until the fresh wort was ready. I then collected the water for 2 batches of California Common, adjusted both to my desired profile, and turned on the elements before weighing out and milling the grain.

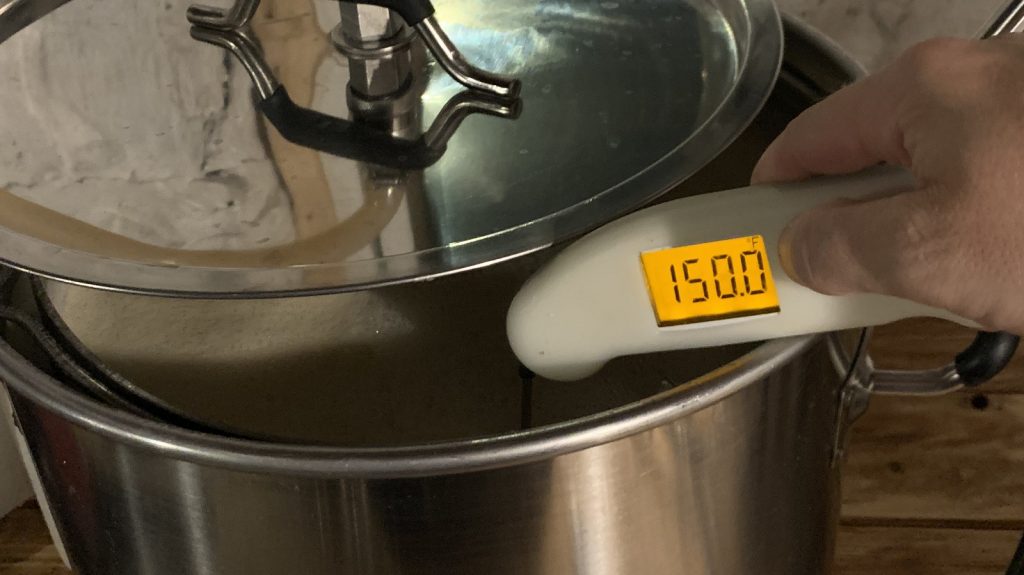

Once the water for each batch was adequately heated, I incorporated the grains then checked to make sure both were at the same target mash temperature.

The mashes were left alone for 60 minutes.

After each hour long mash rest, I removed the grain baskets up and let them drip into the kettles as the wort heated up.

While the mashes were resting, I prepared the kettle hop additions.

The worts were boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times stated in the recipe.

Once each boil was completed, I chilled the wort with my CFC.

To keep things between the batches as equal as possible, I racked both sets to the same 16 gallon/60 liter Speidel fermentation vessel before placing it my chamber to finish chilling.

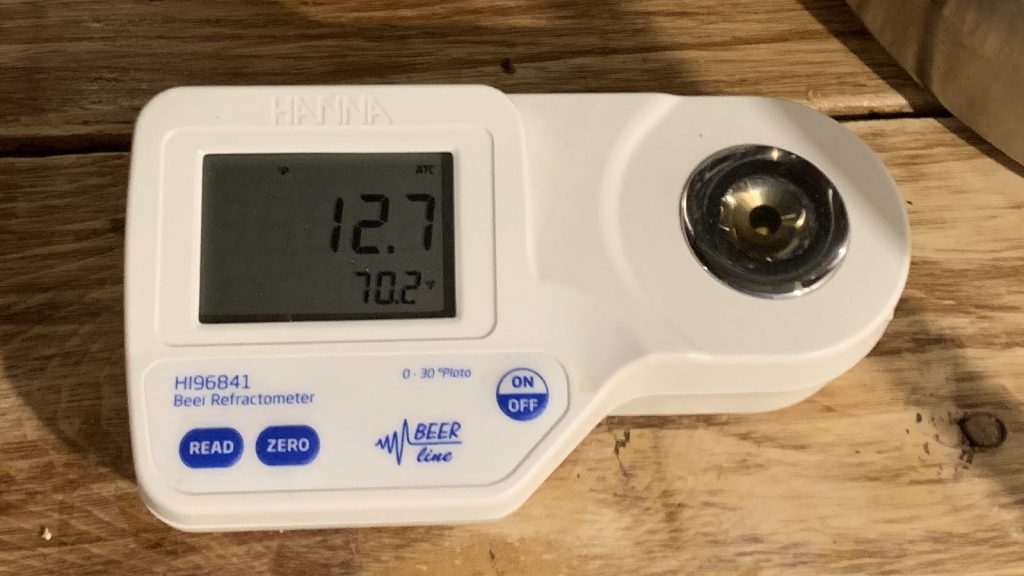

A refractometer reading of the homogenized wort showed it was at my target OG.

With the wort sufficiently cool the following morning, I racked half to a clean and sanitized Brew Bucket before transferring an identical amount to the Brew Bucket containing the Imperial Brown Ale yeast cake.

After pitching the yeast starter into the first batch, I placed the filled fermenters in my chamber set to 55°F/12.8°C.

Fermentation in both beers was active the following morning, at which point I left for a brief vacation. When I returned 5 days later, I raised the temperature to 65°F/18.3°C and left the beers alone for another 10 days before taking hydrometer measurements showing a small difference.

At this point, I racked the beers to sanitized kegs.

Once both beers were packaged, I observed a difference in the way the trub in each batch looked, something that could be a function of the abundance of yeast in the batch racked onto a yeast cake.

The filled kegs were placed next to each other in my keezer and left on gas for 2 weeks before I began my evaluations.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the beer pitched with a yeast starter while the other set was filled with the beer racked onto a yeast cake from a prior batch. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample at least 7 times (p<0.05) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I correctly identified the unique sample all 10 times (p=0.000), indicating my ability to reliably distinguish a California Common fermented with yeast propagated in a starter from one fermented on the yeast cake from a previous batch of Imperial Brown Ale.

While I felt both of these beers tasted good, they were very clearly different. I perceived the beer fermented on the yeast cake as having an aroma that smelled of bright citrus hops, whereas the beer fermented with a yeast starter had a more herbal and slightly resinous aroma, like I expect in California Common. The difference between aromas alone is what enabled me to identify them so handily, but the beer that was fermented using a yeast starter also had a cleaner fermentation character, allowing the grainy-sweet, slightly graham cracker flavors from the malt to shine through.

| DISCUSSION |

Pitching the proper amount of yeast is viewed as being key to producing quality beer, with many brewers taking a “more is more” approach, particularly when it comes to lagers and high gravity styles. One method some use to ensure high pitch rates, arguably more than is necessary, is racking fresh wort onto the yeast cake from a prior batch. When doing this, it’s generally recommended that the initial beer be paler and lower in alcohol than the new beer, though some contend it doesn’t matter. The fact I was able to reliably distinguish a California Common pitched with an adequately sized yeast starter from one racked onto a yeast cake that previously fermented an Imperial Brown Ale suggests this method does have a perceptible impact.

This xBmt was intentionally designed to maximize the impact of the variable– the yeast cake was previously used to ferment a beer that was dark, hoppy, and higher alcohol. As such, it’s difficult to pinpoint what exactly contributed to the beers being perceptibly different, though I’m compelled to think it was a combination of factors. Interestingly, the beers were similar in color, but that’s really where the similarities stopped. While the beer fermented on the yeast cake was good in its own right, it drank more like a citrusy American Amber Ale than a California Common, which may very well be a function of my own bias, though seeing as I was correct on all of my triangle test attempts, I’m wont to believe it was due to the variable.

I absolutely believe racking fresh wort onto a yeast cake is a viable option for ensuring adequate pitch rates, though given the significant results of this and a past xBmt, the recommendation to use yeast that fermented a simpler beer may be good to follow for those who desire more predictable outcomes. I’m certainly not deterred from using this method in the future, though I will be cognizant of the initial beer style and the amount of trub in the yeast cake.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

8 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Yeast Pitch Rate: Yeast Starter vs. Yeast Cake From An Imperial Brown Ale”

Interesting, but not surprising. It should only take about a cup of yeast cake (allowing for 50% viability) to do the job. The excess you included would create the differences you tasted.

Right, these results were more or less what I expected too. But we’ve been surprised before with experiments so it’s good to have another data point in all of these things!

Nice exbeeriment Phil!

Two things that stand out to me and it’s not criticism. Firstly, was the size of the starter right for the purpose of the experiment? The starter was made a few days before hand which would suggest it is a propagation starter. The starter size looks about 1 litre and imperial yeast packs contain 200 billion cells. For a 9P starter you could only expect to propagate about 12 billion new yeast cells. (Source: White & Zainasheff Yeast, table 5.5) This would increase your pitching rate from 0.73 to 0.77 million cells/deg Plato/millilitre. The purpose of the starter stated in the pre-amble was to increase yeast health. In which case I would have made the starter at the beginning of the brew day so the yeast had 5-6 hours to revitalize before being pitched into the wort.

The second thing is the trub from the imperial brown in the yeast cake. That imperial brown ale was hopped with different hops than the final beer and the grain bill contained a healthy dose of black malt. It must be assumed that hop material and colour compounds made there way to the final beer and had an impact on the aroma and appearance.

Putting that aside, what is interesting is that the beer with the starter attenuated to a higher degree that the beer with the yeast cake. This would confirm the notion of over pitching. The appearances of the two FG samples and final beers are also distinctly different, where the yeast cake beer seems to have an abundance of yeast still in suspension. How can the difference in floculation be accounted for?

No worries about submitting any criticism! We welcome any comments that are insightful and constructive, as yours are.

For this purposes of this xbmt, I wanted to test out the usual process that brewers tend to follow to make the control (yeast starter) vs the experimental variable (high OG yeast cake from a different beer style) that some folks like to use. That being the case, whatever is actually lurking in the trub and yeast cake from the IBA was expected to be there and was thought of as a function of the variable. The murky gravity reading is probably more related to the fact that I took those pictures after filling the kegs so it’s just whatever was leftover in bottom of the Brew Buckets. Not surprising that there was a lot of yeast in suspension for that.

As for the theoretical viable yeast counts, my preferred yeast calculator tells me that I’d need something like 250 billion cells per 5 gallons of 1.052 SG beer, meaning that basically any nominal amount of starter wort would suffice for propagating an appropriate amount of cells. What’s more is that we’ve shown a few times that the idea that having a certain number of cell counts based on any calculator may not be as important as we once thought. And for what it’s worth, I’ve been using Imperial Yeast almost exclusively for the past couple years now and their viability/vitality is exceptional. Unless the yeast is old (greater than 6 months or so) or there is some other reason that calls for it, I never use starters and I haven’t noticed any detriment.

All that said, I do think yeast health was a big factor here with terminal gravity as you’ve noted. It would have been fun to do some analysis on the yeast post fermentation. Maybe someday we can have our own laboratory for this stuff!

I reckon if you had used the trub from the same grain bill, then surely your ability to tell any difference would have been reduced. As it stands, with a stout being the primary trub, I was not surprised both the apearance and taste were discernible.

What would have been interesting, had you used trub from the same beer, would have been the days it took to acheive FG, and then any improvment in flavour. That is, comparing the original and subsequent beer.

Maybe use a transmogrifier instead of relying on the yeast: https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1987/03/23

Phil,

Have there been any experiments you know of that were completed to highlight how yeast re-pitched over multiple batches changes the expected performance of the yeast? I had heard that if you continue to reuse yeast it becomes less flocculent and more alcohol tolerant. This would seem to be a viable answer especially if re-pitching to high alcohol beers as only the yeast cells most tolerant of alcohol would survive therefore changing the overall make up almost like the theories of Darwin. In my own experience, I have re-pitched on top of yeast cakes 3-4 times in a row (removing at least half the trub or more each time) and noticed a continual increase in alcohol/attenuation. Just curious.

Jason

As far as homebrewers go, I do not know of any actual published experiments like you’ve mentioned. This is something that we here at Brülosophy have been talking about for a while now and I think we’re going to be running this one soon!

You can look to most any commercial brewery for real-life examples of this, though. Usually they will dump trub etc. and either pitch right on top of the yeast that’s still in the tank or transfer it to another tank (or brink). If memory serves the average number of repitches is something like 7-10, but there are rogues out there who go upwards of 15.

There are a few things I’d keep in mind when doing something like this, the first being maintaining the best possible aseptic technique. Second to that is that while the mileage will vary depending on the yeast strain, the brewer/cellerman, and the brewery, no matter what the yeast will eventually exhibit genetic drift at some point, and those effects on beer can be unpredictable.

There are several academic papers on this type of thing, but this is a very approachable one that’s open to the public from MBAA/White Labs. Worth a read.

https://www.mbaa.com/districts/Ontario/Events/Documents/2014%20MBAA%20Chris%20White%20Yeast%20Management.pdf