Author: Andy Carter

One of the first things all-grain brewers learn is that mash temperature contributes to the overall fermentability of wort. Holding the mash at the lower end of the saccharification rest temperature range activates beta amylase, which results in short chain sugars that are more fermentable, while warmer mash temperatures activate alpha amylase that produce less fermentable long chain sugars.

One seemingly valid and oft repeated “fact” is that certain perceptible aspects of beer including body, mouthfeel, and sweetness are related to temperature at which it was mashed. If aiming for a crisp and dry beer, it’s recommended to mash low, whereas a higher mash temperature is more appropriate for richer beers with a more viscous mouthfeel. Plenty of evidence exists that supports the influence mash temperature has on fermentability and resultant dextrin levels. However, presumptions about the perceptible qualities of dextrins have been called into question by numerous past xBmts comparing beers mashed at different temperatures.

In the time I’ve been brewing, mash temperature has always been something I’ve viewed as contributing not only to wort fermentability and alcohol level, but flavor and mouthfeel as well. Needless to say, I was genuinely surprised by the results from the aforementioned xBmts. When recently looking over those articles, I noticed the beers tended to be fairly simple, which made me wonder if perhaps a recipe with a more complex grain bill might be more influenced by mash temperature.

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between an English Porter mashed at 147°F/64°c and the same beer mash at 163°F/73°C.

| METHODS |

For this xBmt, I designed an English Porter that was inspired by the Brewing Classic Styles recipe as well as previous batches I’ve made, combining a few different specialty grains to round out the depth of malt character.

Cave Shadows

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 gal | 60 min | 24.3 IBUs | 28.5 SRM | 1.053 | 1.009 | 5.7 % |

| Actuals | 1.053 | 1.012 | 5.4 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pale Malt, Maris Otter | 9 lbs | 76.6 |

| Caramel/Crystal Malt - 80L | 1.5 lbs | 12.77 |

| Chocolate Malt | 12 oz | 6.38 |

| Brown Malt | 8 oz | 4.26 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willamette | 28 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 6.5 |

| Willamette | 15 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 6.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| House (A01) | Imperial Yeast | 74% | 62°F - 70°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 36 | Mg 5 | Na 8 | SO4 61 | Cl 35 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

A day ahead of time, I made a single large starter of Imperial Yeast A01 House.

The following day, I started out by collecting two equal volumes of RO water and adjusting them to the same profile.

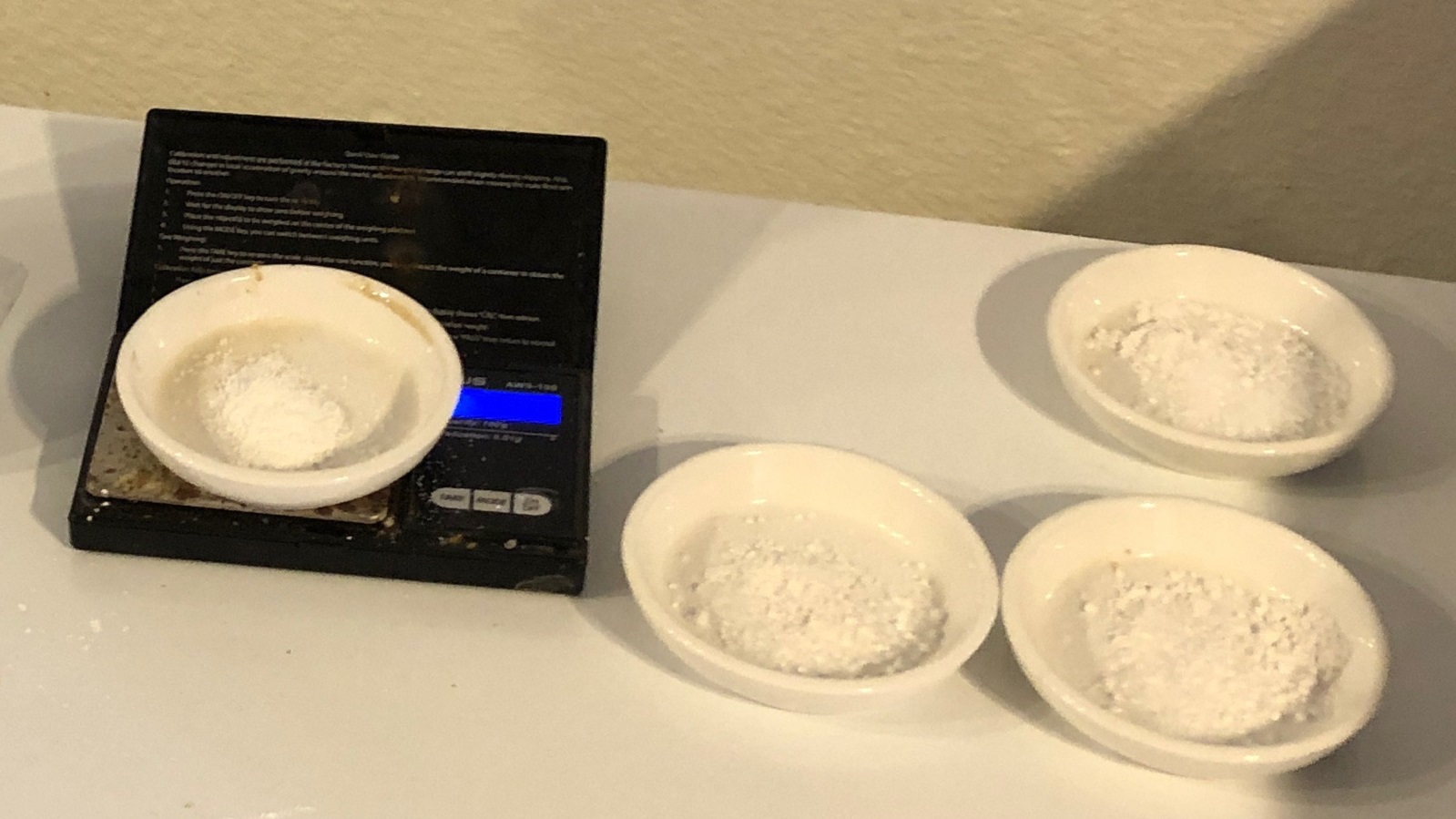

With the water heating up, I weighed out and milled identical sets of grain for each batch.

Given the variable, each batch of water reached their respective strike temperatures at different times, at which point the grains were stirred in and I checked to ensure both hit my target mash temperatures.

The mashes were then left to rest for 60 minutes.

During the wait, I weighed out the kettle hop additions.

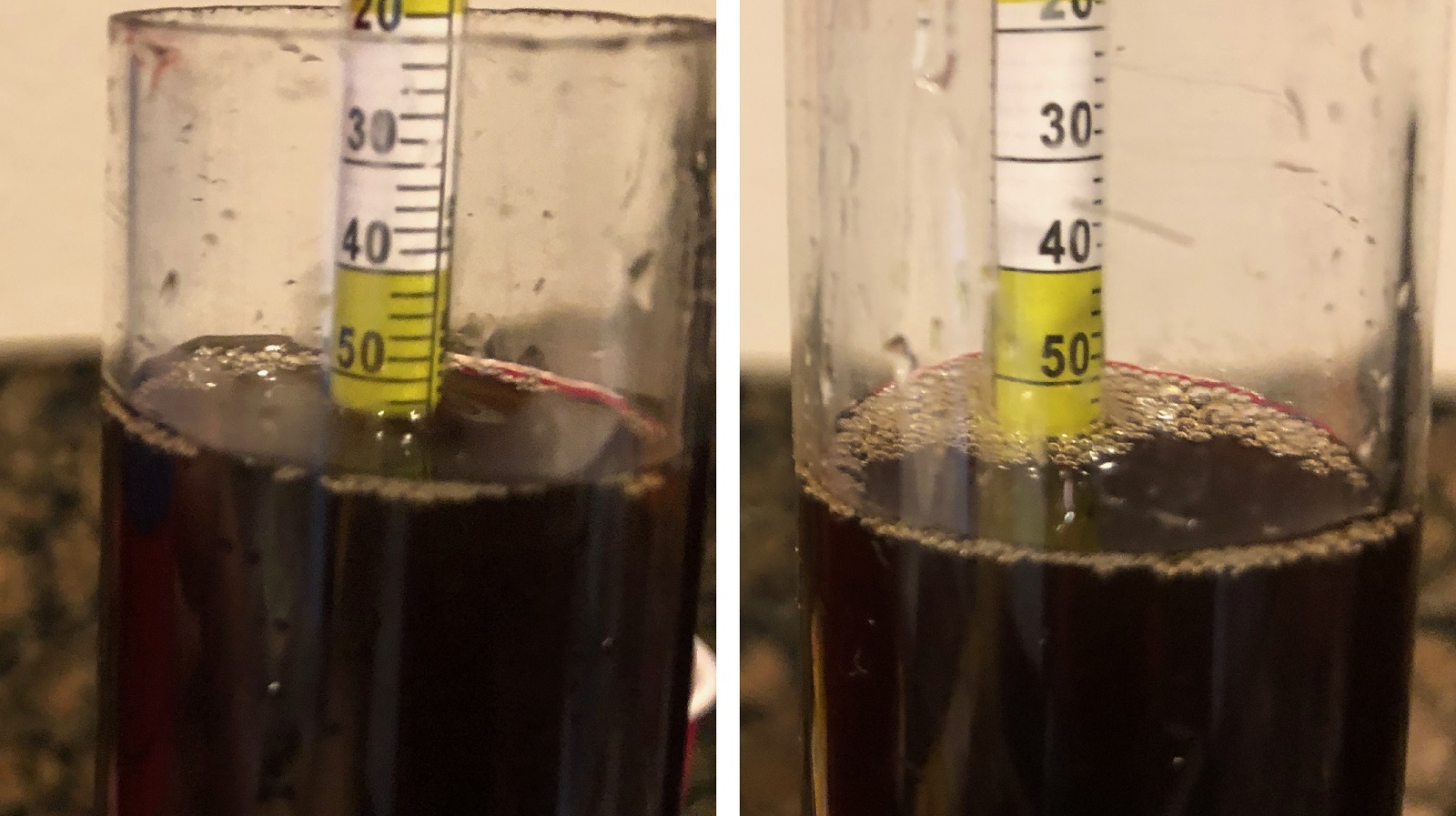

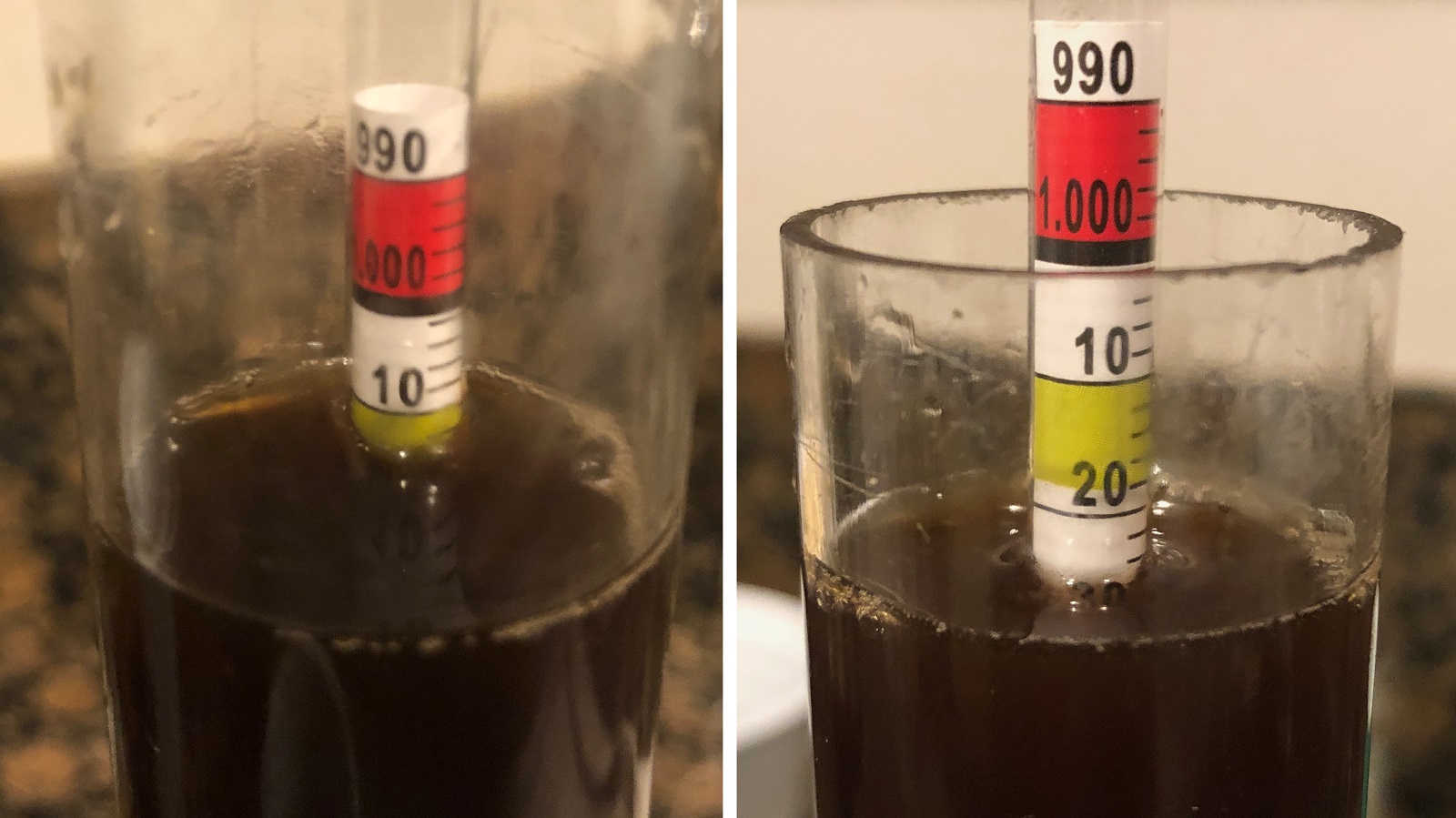

When each mash rest was complete, I batch sparged each batch to collect the same volume of wort then boiled them for 60 minutes before taking hydrometer measurements showing a slight difference in OG.

Equal amounts of wort were racked to sanitized 6 gallon/23 liter PET carboys that were placed in my fermentation chamber and allowed to finish chilling. A couple hours later, I split the yeast starter evenly between the batches and left them to ferment at 66°F/19°C. When checking on the beers 24 hours later, I noticed the low mash temperature batch was much more active than the high mash temperature version, which is consistent with observations in past xBmts on this variable.

After 3 days of fermentation, I raised the temperature to 70˚F/21˚C and left them alone for 10 more days before taking hydrometer measurements showing a rather drastic, though expected, difference in FG. This resulted in the low mash temperature beer being 5.4% ABV and the high mash temperature beer being 3.9% ABV.

The beers were then racked to sanitized and CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my keezer, burst carbonated, and left to condition for 2 weeks before I began evaluating them.

| RESULTS |

Due to social distancing practices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, data for this xBmt was unable to be collected in our typical manner. As such, temporary adaptations were made involving the author completing multiple semi-blind triangle tests in as unbiased a way as possible.

Utilizing 4 opaque cups of the same color where 2 were inconspicuously marked, one set was filled with the low mash temperature beer while the other set was filled with the high mash temperature beer. For each triangle test, 3 of the 4 cups were indiscriminately selected, thus randomizing which beer was the unique sample for each trial. Following each attempt, I noted whether I was correct in identifying the unique sample. Out of the 10 semi-blind triangle tests I completed, I needed to identify the unique sample 7 times (p<0.02) in order to reach statistical significance. In the end, I chose the unique sample 9 times (p=0.0004), indicating my ability to reliably distinguish an English Porter mashed at 147°F/64°C from one mashed at 163°F/73°C.

Both of beers shared inviting aromas of chocolate and coffee aroma, and I was unable to tell them apart on smell alone, though I did perceive distinct flavor differences. To my palate, the high mash temperature beer lacked complexity and had an ashy note, whereas the lower mash temperature version had a deeper roast and graham cracker flavor that lingered a bit longer. Oddly enough, it felt to me like the lower mash temperature beer was heavier and fuller bodied. While I enjoyed both of these beers, I preferred the lower mash temperature one for what I perceived to be more depth of flavor.

| DISCUSSION |

Mash temperature is used by brewers as a sort of knob to control things like attenuation, sweetness, and alcohol level in beer through the activation of alpha and beta amylase enzymes. Going against the results of past xBmts on this topic, I was able to reliably distinguish an English Porter that was mashed at 147°F/64°C from one mashed at 163°F/73°C, suggesting the different mash temperatures did have a perceptible effect.

As easy is it to chalk these results up to experimenter bias, it’s worth considering the fact that the contributors from the prior xBmts struggled to distinguish beers mashed at different temperatures. Presuming my performance in this xBmt was valid, the question then arises– what caused the difference? One plausible culprit is the 1.5% ABV difference between the beers, though seeing as this was also the case in past xBmts, it seems less likely. Perhaps it had something to do with the complexity of the grain bill, which would suggest beers with a higher proportion of specialty malts react different to mash temperature than simpler beers. Ultimately, mash temperature affects beer in various ways, so it’s impossible to know for sure what exactly it was that made these English Porters perceptibly different to me.

While I noted a preference for the lower mash temperature Porter, it’s important to keep in mind this was a test of relatively extreme differences. Typically, I choose a mash temperature that falls somewhere between the two extremes, and the results of this xBmt haven’t influenced me to change that. One thing I did take away from this experience is that the low mash temperature beer didn’t suffer and still tasted like a good English Porter, which will help me worry less in those times the temperature drops more than expected over the course of the mash rest.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

26 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Mash Temperature: Low Vs. High In An English Porter”

The inverse of this is mash at the same temperature and use yeasts with different attenuation characteristics.

I found that the Rochefort yeast, by propagating it, is a var. diastaticus strain, which really attenuates almost 100%. I brewed different beers with it, a 4,5%, a 6,6% and a 9% beer. All of these beers have a nice body. They taste a bit dry, but I presume this is more because in all of them I used more sulphate.

I actually only know one beer that is so dry that it lacks body, and that is “Seefbier”, by the “Antwerpse Brouw Company”. I think it takes effort, not just a difference in mash temperature.

I think it makes sense when you think about it. High order sugars are flavor neutral, once you chop them up either in the mash or with a diastaticus, smaller flavor active sugars (and derivatives) are.formed. It just goes against conventional wisdom that body in a beer is due to higher order sugars.

Thanks. I love this topic. I have also found that I get a very full flavor from low mash temp beers. I haven’t done a side by side but have done a ton of beers with high mash temps, up to 170F. I really like the lower ABV in some beers. I can make a very nice stout that is under 4% that tastes way better than one mashed low with less malt. I think in this case maybe the alcohol does have some impact on flavor. Maybe try adding some everclear or vodka to the low abv one to see if it seems fuller and sweeter? Another comparison that would be interesting is raise the OG on the high temp beer so that the final ABV between the two is very close. i bet the high mash beer would be fuller tasting.

Thanks!

I may be going very beyond my yeast knowledge here, but would it make sense that the beer with higher attenuation had also increased glycerol production due to its longer fermentation? Glycerol amounts will certainly impact the body and sweetness levels of the finished beer leading to what was may be perceived in this xbmt.

I would agree with this line of reasoning!

I’v noticed you are using the BrewZilla. I have the BrewZilla also, and it has difficulties to keep the exact temperature during the entire mash period. I wonder how you can conduct this experiment with less extreme temp, let’s say 63 and 67 C.

Since the malt basket/pipe does not drain as quickly as the pump can move, that is what will throw off the display thermometer. I rely on an accurate hand thermometer to ensure the right mash temp.

Great write up. I have had a similar experience when doing this same thing. When I did the higher mash I was trying to achieve better head/foam formation and retention. Did you notice anything in regards to this? Especially after they had proper time to condition. Thanks!

I’ve done a million high mash temp beers and they always have lower head retention in my experience. They can make a comeback with extended aging though, like when the beer is super clear after at least a month or more.

Anecdotally, there seemed to be a difference when having glasses of beer for enjoyment; I will watch this more carefully and get back to you.

I guess the base question is “How do you promote body in a beer?”. I high mashed(160F) some base malt & added it to a cider recipe to try to make the cider less dry, The effect was pretty subtle if there at all.

Thanks for this great experiment! Because you noted an ashy character to the high-temp mashed beer, I’m wondering what would change if you added the heavily roasted grains post-mash, per Gordon Strong’s advice, thus exposing them to the high temperatures for a shorter period of time. You’d still have the differences in enzymatic activity, but perhaps without the difference of a super ashy beer.

I would say the ashy flavor was present but not dominant; it would be interesting to remove the dark grains until the end of the mash to see if the beers become more alike.

Andy, Could you detect a difference of sweetness between the two?

I would say the lower mash temp came across to me sweeter, but not extremely so.

Why did you go with higher sulfates than chlorides? I always push chlorides on malt forward beers. they make the malt flavor pop.

This was based on the “Black Balanced” setting in Beersmith.

What’s next, decoction mashing a beer that is 65% black patent?

You mentioned an “ashy” flavor — I wonder what the effect would be of cold steeping the darker grains? You might avoid some of the more burnt notes.

Was there a difference in mash ph?

One of the difficulties with this types of tests is: to what extent do you keep it a single variable or do you adapt others to the one you a re trying to test? Typically, when there is such a drastic difference in one parameter, in a normal brew session you would also adapt other parameters. For example, here, 1h at 147 may be barely long enough (hence the pre-boil gravity being slightly lower). On the other end, 163 for 1h is way overkill. 30min would probably be long enough. I wouldn’t even be surprise if you get full conversion at 15 min at such a high temperature…

there is no right or wrong answer to this question, but it should be kept in mind.

I am not surprise by the lower temperature one being perceived as sweeter:

1-The alcohol (to a certain extent) brings some sweetness.

2-The more fermentable sugars (beta-amylase) are also sweeter tasting that the less fermentable ones (alpha-amylase). If the yeast leaves some beta-amylase behind, it is not suprising that the lower temperature mash would leave a little more left than the higher temperature mash. Don’t think the imperial A01 would leave too much though…

3- More attenuation means more fermentation by-products (such as slightly fruity esters, which can increase the perceived sweetness)

My second brew was a irish red several years ago. I messed up my mash temperature and ended up with a 4% ABV beer finishing a 1020. To my surprise it was neither thick nor sweet. It just tasted close to what you would expect from the 5.5% normally attenuated beer. Kinda like the results from the different exbeeriments on the topic…

I think the whole myth of mashing low for low body/maltiness/sweetness and high for more body comes from taking things in reverse. What people should say is: if you want a beer that has less, for the same ABV, you can put less malt but mash lower. if you want more body, add more malt and mash higher.

In this example, one can probably say that mashing high allowed you to brew a 4% porter that has more body than what you would expect from a 4% porter.

What people shouldn’t say is that, for a specific recipe, changing the mash temperature will change the body of the beer.

Great comment

I appreciate all of this! For mash pH, measured at room temp, low mash temp pH: 5.56, high mash temp pH: 5.38.

Thanks for the pH info.

It really looks like the alpha and beta amylase pulled the pH into there respective favorite pH:

http://howtobrew.com/book/section-3/how-the-mash-works/mashing-defined

Just realized I got the pH reversed. I guess my comment didn’t make much sense… The mash pH are actually the opposite of what I would have expected if the enzymes were pulling it into their favorite ranges.

Any idea why they would be that way?

Find it interesting you could distinguish a Porter yet not the lagers done earlier. Somehow makes sense to me. I am also not convinced that knowing what you are looking for influences your tests. COVID be damned I say.. still – Not as transparent as 30-40 general beer drinkers giving their feedback. Whilerhs unaware of what they were supposed to be looking g for.

Has there been any testing of mashing over say, 3 hours, where mash temps graduated from 154 degrees down to 146 for the duration of the mash! Would I not enjoy al,the b emeritus of the aplpha and beta breakdowns,and their respective impact on flavour, taste, ABV etc.

I ak this, as I recently left an IPA mashing in my garage, as I had to drop my kids out and about, so left it at 154 degrees. I came home 3 hours later, and it had dropped down to 146. Beer is in fermenter a week, and taste pretty good. My attenuation was pretty decent, from 1.056 to 1.008, and not sure it is comlaltes yet.

Have I not just effectively step mashed in reverse on doing this. And would I not have a more rounded final productj.

Sorry for errors in my previous response. My iPad keyboard gets jumpy at times. I’d be interested to see the results in this Bxmt with perhaps just a moderate 3-4 degree mash temp swing, and see if any notable difference. I suggest you’d be pressed to find a difference.

A Long mash time 3 plus hours, versus 1 hour or even 30 minutes mash would be another excellent Bxmt, in my opinion. Don’t control temps at all. Just let them all begin at say 154 degrees, and naturally drop. Again, be interesting to see this done with a pilsner, and your porter for sake of comparison.