Author: Marshall Schott

Back when Northshore was still a junior high and had an offensive mascot, us students were required to participate in a weekly “Wednesday Run” where we had about 30 minutes to complete a 1.25 mile/2 km course around the school. I was unfortunate enough to have PE 5th period, the second to last class of the day, which not only meant my 6th period classmates had to deal the consequences of my insecurity-derived avoidance of group showers, but it was after lunch where I usually spent 20 minutes sprinting my chubby ass up and down a basketball court pretending to be the next Gary Payton. Needless to say, when it came time to run, I was already exhausted and often resorted to walking the track with a curiously entertaining group of other kids.

This experience is what comes to mind when I consider the commonly recommended method for reusing yeast. The claim goes that it’s best to pitch slurry from a lower OG beer into a higher OG beer because going in the opposite direction can lead to off-flavors caused by stressed, or exhausted, yeast. In essence, we want our yeast running the track, not walking it with a bunch of other lazy cells.

I realized my opportunity to finally test this variable out while I was kegging a Barleywine I recently brewed. At 1.099 OG, it’s safe to say the yeasts worked their tails off to ferment that beer, so I harvested some slurry and prepared for my next xBmt!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between Blonde Ales fermented with either a fresh pitch of yeast or slurry of the same strain that was previously used to ferment a 1.099 OG Barlewine.

| METHODS |

Wanting to make sure any impact of the variable wasn’t hidden by other ingredients, I designed a simple Blonde Ale with a moderate OG and minimal hop additions.

Leister

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 30 min | 21.7 IBUs | 5.8 SRM | 1.048 | 1.011 | 4.9 % |

| Actuals | 1.048 | 1.007 | 5.4 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lamonta (Mecca Grade) | 9 lbs | 85.71 |

| Metolius (Mecca Grade) | 1.5 lbs | 14.29 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centennial | 7 g | 30 min | First Wort | Pellet | 9 |

| Simcoe | 7 g | 20 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.1 |

| Centennial | 7 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 9 |

| Simcoe | 7 g | 10 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.1 |

| Centennial | 4 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 9 |

| Simcoe | 4 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 13.1 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flagship (A07) | Imperial Yeast | 75% | 60°F - 72°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 75 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 114 | Cl 49 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

While the Barleywine was being transferred to a keg, I hit the internet and found I’d need approximately 400 mL of dense yeast slurry to match the 200 billion cells in a pack of Imperial Yeast. Once the keg was filled, I swirled the remnant beer in the fermentor then filled a 1 quart mason jar with the loose slurry and put it in the fridge. The following day, I found the slurry had compacted to almost exactly 400 mL– nice!

Later that evening, I collected my water for the following morning’s brew.

While the water was slowly running through the filter, I weighed out and milled the grains.

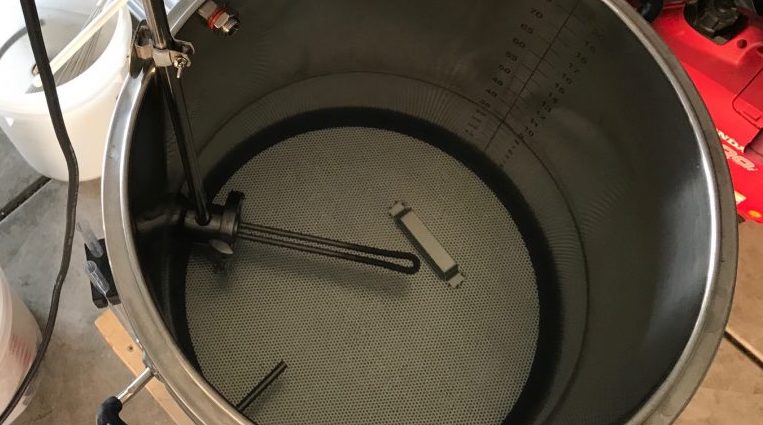

After adjusting the water to my desired profile, I dropped my heat stick in and set it on a timer to turn on a couple hours before I woke up the next day.

Greeting me the following morning was hot strike water, which I gently added the milled grain to.

The temperature ended up settling just a hair below my target due my impatience, nothing I was concerned over.

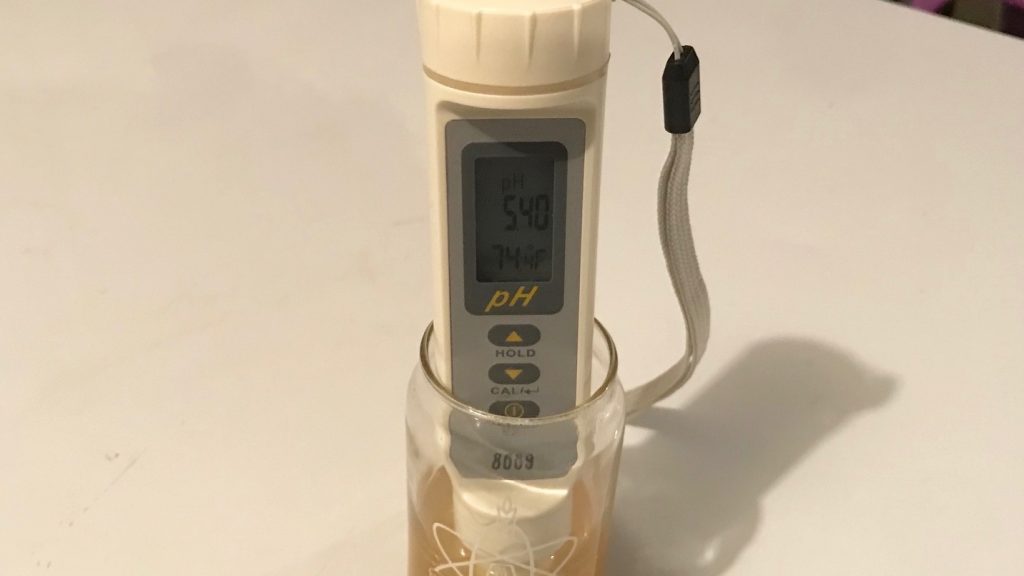

I stole a small sample of wort about 15 minutes into the mash and chilled it down before taking a pH reading showing things were right on track.

Toward the end of the mash rest, I measured out the small amount of hops that would be used in this batch.

At the end of the 60 minute mash, I collected the sweet wort in a graduated bucket then transferred it to my kettle.

I lit the burner then moved on to cleaning my mash tun while the wort was heating up.

The wort was boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times stated in the recipe.

Once the boil was complete, I quickly chilled the wort to slightly warmer than my groundwater temperature.

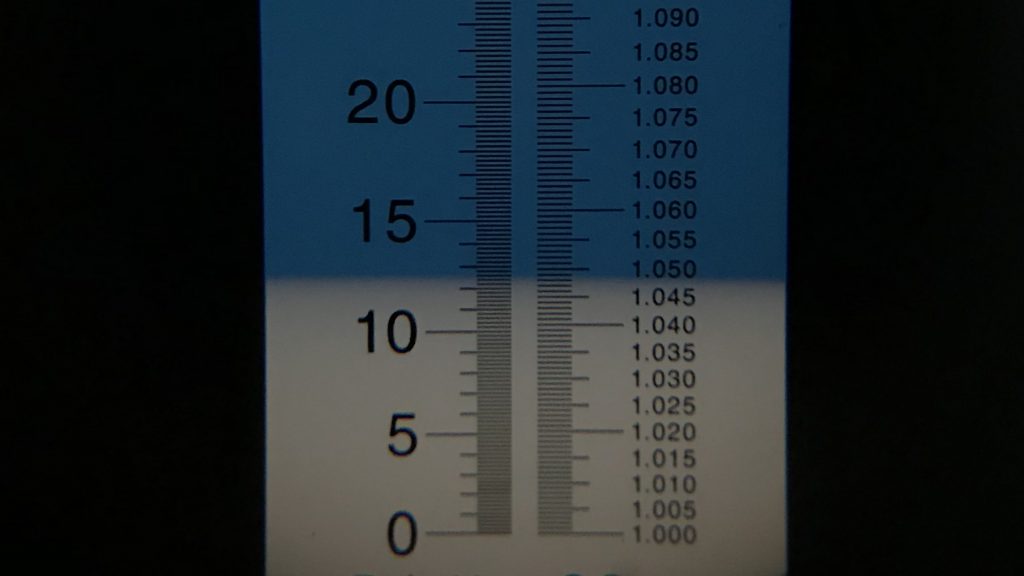

A refractometer reading showed I hit my target 1.048 OG.

I then filled separate Brew Buckets with identical amounts of wort.

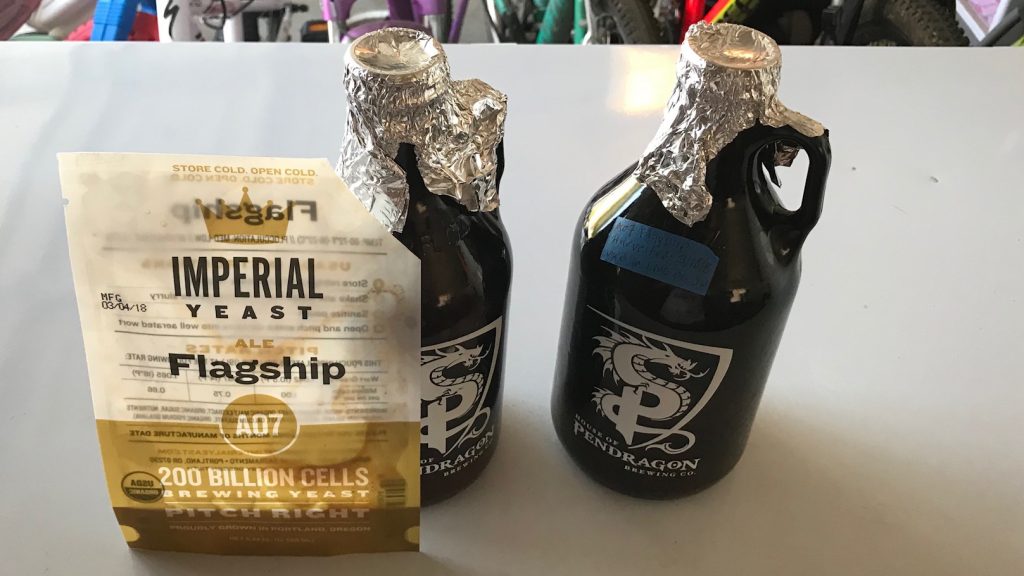

The fermentors were placed in my temperature controlled chamber to finish chilling, at which point I split 1000 mL of leftover wort between a couple growlers, pitching the fresh pack of Imperial Yeast A07 Flagship into one and the slurry into the other.

I returned 4 hours later and found both worts had stabilized at my target fermentation temperature of 66°F/19°C, so I pitched the vitality starters and connected my CO2 harvesters.

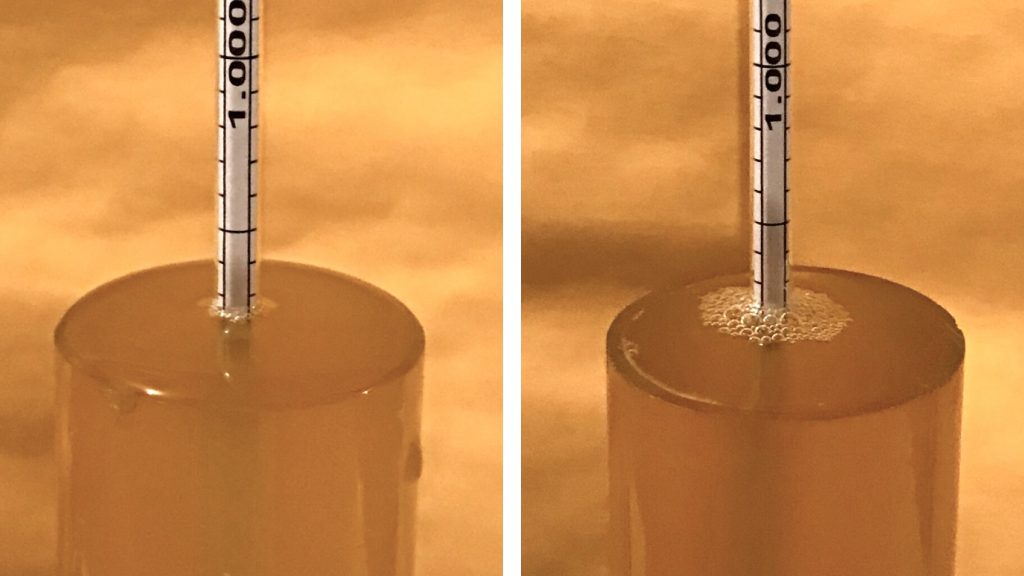

I heard bubbling coming from my chamber later that evening and decided to take a peak under the hood. I found the slurry pitched beer had already developed a solid kräusen while the fresh yeast batch was just getting going. Pretty impressive for just 8 hours post-pitch.

I raised the temperature of the chamber to 72°F/22°C 4 days into fermentation to encourage complete attenuation. After another 3 days, I took hydrometer measurements confirming both beers had reached FG.

I cold crashed the beers and fined them gelatin before proceeding with transferring them to CO2 purged kegs.

The filled kegs were placed in my cool keezer and burst carbonated. After a day at 50 psi, I reduced the gas to serving pressure and let the beers cold condition for 6 days before moving forward with data collection.

| RESULTS |

A total of 21 people of varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the beer fermented with fresh yeast and 2 samples of the beer fermented with slurry previously used to ferment a high OG batch in different colored opaque cups then asked to identify the unique sample. At this sample size, 12 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to identify the unique sample in order to reach statistical significance, which is exactly how many were able to do so (p=0.021), indicating participants in this xBmt could reliably distinguish a Blonde Ale fermented with a fresh pitch of Imperial A07 Flagship yeast from one fermented with the same strain previously used to ferment a 1.099 OG Barleywine.

The 12 participants who made the accurate selection on the triangle test were instructed to complete a brief preference survey comparing only the beers that were different. A total of 7 tasters reported preferring the beer fermented with fresh yeast, 4 said they liked the beer fermented with the high OG slurry, and 1 taster reported perceiving no difference.

My Impressions: When tasting they FG hydrometer samples for these beers, I was pretty sure I could detect a difference, though it was slight enough that I assumed it’d disappear after a period of cold conditioning. Nope. Out of the 8 semi-blind triangle tests I attempted, I accurately identified the unique sample 6 times, and in each case I made my determination primarily based on aroma. Whereas the beer fermented with fresh yeast smelled like a pretty standard pub-style Blonde Ale, the one pitched with high OG slurry had a sort of rubbery thing going on. It certainly wasn’t overwhelming, the beers were way more alike than they were different, but the aromatic difference was at least noticeable. As far as flavor goes, the beers tasted nearly identical to me– clean and malt forward with just a hint of American hop character.

| DISCUSSION |

With most commercial yeast labs providing limited cell counts, one approach to ensuring adequate pitch rates involves reusing yeast from one batch to ferment another batch, which also happens to be pretty cheap. Given the stress put on yeast during the fermentation process, a common recommendation is to only repitch slurry that was used to ferment a beer with a lower OG than the new batch in order to prevent off-flavors. Blonde Ale to IPA to Barleywine. Something like that.

I generally trust science more than hunches, though I’ve occasionally questioned the logic of this recommendation and wondered just what could come from pitching a proper amount of slurry from a big beer into another batch. It seemed to my microbiologically ignorant mind that any byproducts of stressed yeast would present in the original beer, and if they weren’t there, the yeast would do fine in the less stressful environment of a lower OG beer. Shining a light on my naïveté, tasters in this xBmt were indeed capable of distinguishing a Blonde Ale fermented with Barleywine yeast slurry from one fermented with fresh yeast.

In considering the implications of these results, I can’t help but think of the fact the aforementioned advice is provided as a way to avoid producing crappy beer. Thing is, the differences between the samples were really subtle, and while the fresh yeast version won the preference of more tasters, the beer fermented with Barleywine slurry was in no way bad. I say this not as advocacy for the practice, I’ll likely never do it again, but in a pinch, I think it’s a decent approach that will likely produce a perfectly fine beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

26 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Fresh Yeast vs. Slurry Harvested From A High OG Blonde Ale”

Your exbeeriments always seem to be timely with my brewing habits. While I am not comparing high gravity slurry to pure, I am currently fermenting a hefe wort with a slurry from a previous dunkelweizen (cleaned a couple times) and another with a clean pitch of wyeast 3068 to test if the previous dark wort affected the yeast at all.

Keep up the great work you are doing. It helps more than you know.

Cheers.

Thanks for another great experiment!

I am curious about how that 400 mL quantity of slurry was determined. How was the amount of hop trub, malt trub and dead yeast trub in the slurry estimated? Don’t those things vary significantly based on the individual beer recipe and brewer’s methods? And so perhaps your two beers actually started with very different cell counts?

“the beers were way more alike than they were similar”

What is meant here?

It would be interesting to compare harvested (ie washed) yeast to the slurry and the fresh packaged yeast. Your observation that the slurry was more active at the beginning than the new yeast would indicate that the yeast was not “tired” from the Barleywine fermentation. In fact your cell count may have been much higher than the packaged yeast because your method of estimating the cell count (ie 400 ml of slurry) would be very rough at best. A contrarian point of view suggests that slurry yeast might be more vital than packaged yeast, just having had a good feed & some exercise, whereas the packaged yeast was sleeping. The vitality starter should have neutralized that, but the slurry may have had a head start. I suspect that the other elements of the slurry which should be washed out by harvesting may account for the slight difference in the taste of your 2 brews. This is the argument used for not reusing yeast from highly hopped brews. I always harvest my yeast. I wash it several times before refrigerating it. I have not picked up on transferred flavours from hops or trub using this method. I sometimes keep washed yeast for a long time ( 6- 12 mo or more), and always make a starter a day or 2 before brewing and have not had problems with it. Dave Grey’s comment above indicates that he is using harvested yeast, which is substantially different than slurry.

Nice work. Can you please provide the math for determining the amount of slurry? (or a link to it)

Thx

Pitch rate will have a far bigger impact on the beer than what the last ferment was, and since you (presumably) didn’t actually count your yeast…

Just a note to say 1.25 miles is a lot more than .4kms. I’ll have taken the 400metres over the 1.25 miles given the choice.

Perhaps I’m missing something here. I just don’t understand what the attraction is to re-use yeast. Is there some sort of adaptation that results in better performance? Or overwhelming time savings? Initially I overbuilt a starter, saving a pint. The evening before brew day I warm it up and prepare a starter, stabilize temps and put it on the stir plate. Morning comes, I’ve got plenty of action, when wort cools, I pitch, keeping a pint of starter for next batch. Next morning post-pitch I’ve got a party going on in the fermenter and a clean strain in the fridge for next batch. What advantage am I missing out on using old yeast?

You’re right, Easier than harvesting and definitely cleaner than using a slurry. Also better than harvesting & keeping several jars of the same yeast because it gets refreshed every time you make a starter, as long as it doesn’t get contaminated, which is also a concern when harvesting or using a slurry.

It’s a pro brewer thing. Some of our fresh pitches are in the hundreds of dollars, and it would take a large amount of valuable floor space for a fermenter dedicated to making starters.

2nd and later generations generally attenuate better, and ferment faster and “healthier” – at least according to professional brewers. I personally found this to be especially true for belgian strains, where you often want a high degree of attenuation.

Reusing yeast: ensures quick start and Is free. I get fantastic results pitching 400ml slurry lagers and 250ml for ales.

I’ve used methods similar to what you described many times over the years. I’ve also froze yeast and maintained yeast banks on slants. All methods have their pros and cons. But in my opinion, if you have a work horse yeast that you use often nothing is easier, more reliable, and cost effective than harvesting and re-pitching yeast. If you harvest properly and use within 1-3 weeks you’ll brew great beer. I typically re-pitch 6 generations and then restart from either a slant or purchase new yeast. That said I’ve gone as high as 8 generations with no issues. Bottom line in my experience its a win win win. Easier….no starters needed and I’ve always hated messing around with DME and starters (especially because I need a lot of starter as I typically brew 20-30 gallons). Better beer…especially generations 2-5 I’ve found. Cheap…DME is pricey and I don’t use any until I re-start with fresh yeast. In the end we each have methods we’re comfortable with. I’ve changed mine at least half a dozen times over the past 26 years and will probably continue to do so. Cheers

No way a compacted yeast cake has only those viable cells… i guess that 400 ml of thick slurry has over 800 billion cells. In fact, using average numbers of yeast count per Ml and average non yeast content, i think 100 Ml of that slurry would be enough to provided a regular pitch. But that’s just my opinion.

Hey Marshall, I suspect you have a second independent variable here… Obviously you have to account for trub and some viability loss to the high-gravity fermentation, but I’ve never encountered a packed slurry with a density less than about 2 billion/mL, so the fermenter using harvested yeast probably started with at least double the pitching rate of the control. Just a thought.

Cheers,

Sean

Do yeast get old and tired? I though they kept dividing into new cells, while the old ones die and drop out. So in theory you can keep reusing yeast until the population of mutants or wild contaminants grows enough to affect the flavour profile. I’m not sure how many cycles that is..

For a fair comparison I’d have pitched some clear barley wine into the fresh-yeast batch as the 400ml slurry obviously contained quite a bit – perhaps enough to be detectable in a light beer .

I think it would be more correctly described as genetic mutation. The theory being that yeast would be stressed by being exposed to high gravity wort and mutate in ways unfavorable to beer flavor. Yeast in commercial breweries is generally stepped up from single-cell cultures under controlled conditions.

I cannot imagine that the pitching rate was the same. Seems like a decent enough variable that sounds be considered

I’ve lately tended towards over making my starters, but have used some slurries and even just racked my wort onto an old yeast cake too.

I considered the Belgian practice of reusing their yeast for years and thought that the idea of yeast getting”tired ” or producing off flavors had to be bunk. Now I’ll have to reconsider that.

But i still have conceptual difficulty with the idea that a vat full of malt is a high stress environment or that the yeast would need to work “hard” in it. Sexual reproduction does occur in times of stress because of the benefit of recombining genes to find a more adapted progeny – that then goes on to reproduce assexually to great clonal success.

I think more needs to be done to control the variables and investigate further .

Alcohol is toxic to yeast, so.. yes. A vat full of malt (or in this case, a vat full of high alcohol barleywine) can be a very high stress environment for the yeast.

I really enjoy all your exbeeriments, have learned that really we’re going to make beer!

I hope someone though can explain the significance on these tests when one person who chose right then claims no difference. Isn’t then the choosing correctly pure luck? And in this case if to throw out their “guess” this is no longer significant statistically. I’ve seen this before and it boggles my mind that this hasn’t been a point to reconsider the result. Or maybe it’s just been too many years since my stat classes in college!

Would be interested in understanding.

Been a long time since i had to take stats, but i believe the formula takes guesses into account. The taster doesn’t get a ” I don’t know” option. The question has only two alternatives – did the taster pick the correct sample or not. If insufficient numbers pick the correct result, the test says there is no difference and basically everyone could have been guessing!

That inquiry is made quite often.

Per Chris, yes, successful guessing is part of the assumption and built into required results for the number of people who select the different beer.

what is the article about??

I was curious about the discussion about the viability of yeast when residing in %10ABV. I know many people who keep a slurry from their prior batch simply leave it in the beer that was dumped during the yeast dump. Maybe topped up with sterile water. Would this assume that the yeast’s viability would decrease much faster than it would if you would pour off as much beer as possible replacing it with sterile water?

Also, much of this topic was discussing using previously high OG yeast in a much lower OG wort. I would be curious to see if this difference would be noticed when using that same yeast in the same OG beer and if possible the same recipe.