Author: Jake Huolihan

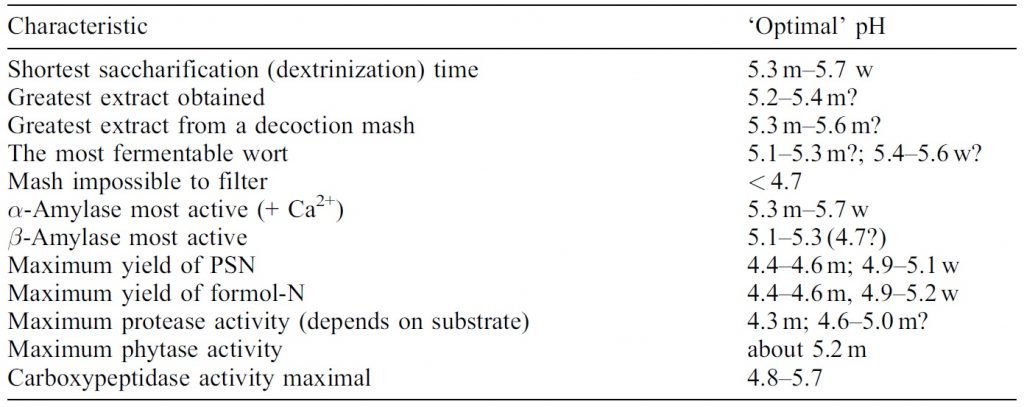

There are many components brewers focus on when it comes to converting starches from grain into fermentable sugar, from the various mashing methods and temperatures to the amount time the grist in left to mash. Influenced by numerous factors such as grist composition, water source, and liquor volumes, mash pH is another aspect I see come up fairly often. Brewers have widely accepted an ideal mash pH within a range of 5.2 to 5.6, though my research hints that it may not be so cut and dry. In his book, Brewing Science and Practice, Dennis Briggs notes the optimal mash pH may be different depending on the desired outcome. For instance, according to Briggs, if the focus is solely on saccharification, a mash pH bet 5.3 and 5.7 would be preferable because it provides the shortest conversion time; however, if optimal extraction from the malt is the goal, the brewer would be better off employing a mash pH of 5.2 to 5.4.

I’ve never knowingly mashed a beer lower than about pH 5.2, though I recently heard a rumor that one of my favorite breweries recommends mashing at pH 4.5 and was inspired to try it for myself!

| PURPOSE |

To evaluate the differences between a beer made with a notably low mash pH and the same beer made with a mash pH accepted to be in the normal range.

| METHODS |

I’ve seen anecdotal reports of certain commercial lager breweries employing low mash pH floating around the internet, and while I was unable to substantiate these claims, I decided to brew a clean Pilsner for this xBmt.

pHilsner

Recipe Details

| Batch Size | Boil Time | IBU | SRM | Est. OG | Est. FG | ABV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 gal | 60 min | 32.7 IBUs | 3.1 SRM | 1.046 | 1.011 | 4.6 % |

| Actuals | 1.046 | 1.01 | 4.7 % | |||

Fermentables

| Name | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|

| Weyermann Pilsner Malt | 10 lbs | 90.91 |

| Oats, Flaked | 1 lbs | 9.09 |

Hops

| Name | Amount | Time | Use | Form | Alpha % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertau Magnum | 15 g | 60 min | Boil | Pellet | 14 |

| Hallertau | 15 g | 30 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.5 |

| Hallertau | 15 g | 5 min | Boil | Pellet | 4.5 |

Yeast

| Name | Lab | Attenuation | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern German Lager (WLP838) | White Labs | 72% | 50°F - 55°F |

Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 50 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 50 | Cl 50 | HCO3 16 | pH 4.45/5.33 |

Download

| Download this recipe's BeerXML file |

Two days prior to brewing, I made a giant liter starter with 2 packs of WLP838 Southern German Lager yeast, the volume determined by my preferred pitch rate calculator.

I began preparing for brewing by collecting pure RO water the a day ahead of time.

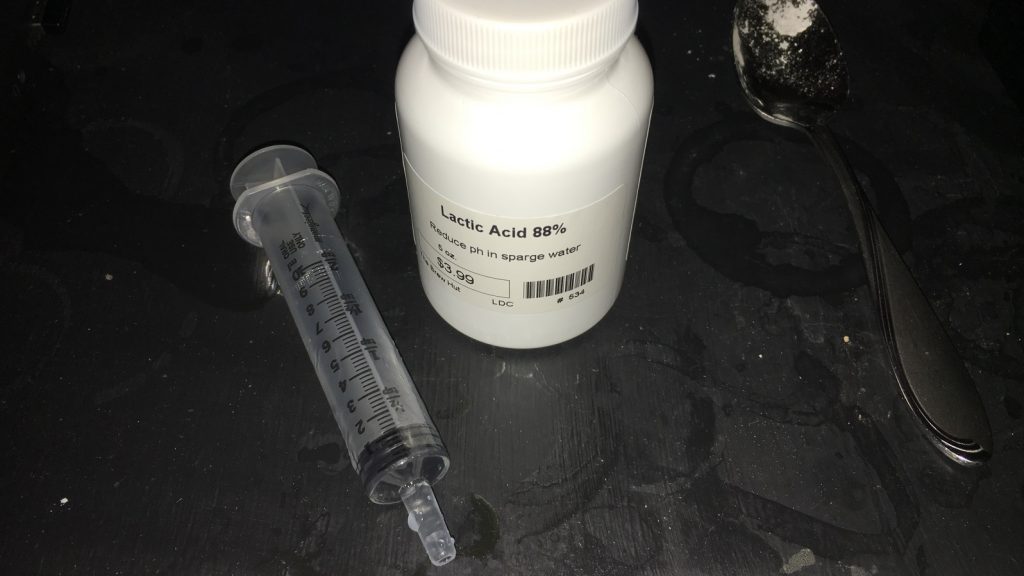

After adjusting the water for both batches with the same amount of minerals to achieve my desired profile, I introduced the variable by adding 19 mL of 88% lactic acid to the low pH batch, which the Bru’n Water Spreadsheet predicted would result in a mash pH of 4.5.

Staggering the batches by 20 minutes to save my sanity, I started off my brew day by firing up the burner under one of the kettle’s of strike water.

I measured out and milled the grains for both batches as the strike water was heating.

Each batch was mashed in and settled at the same target temperature.

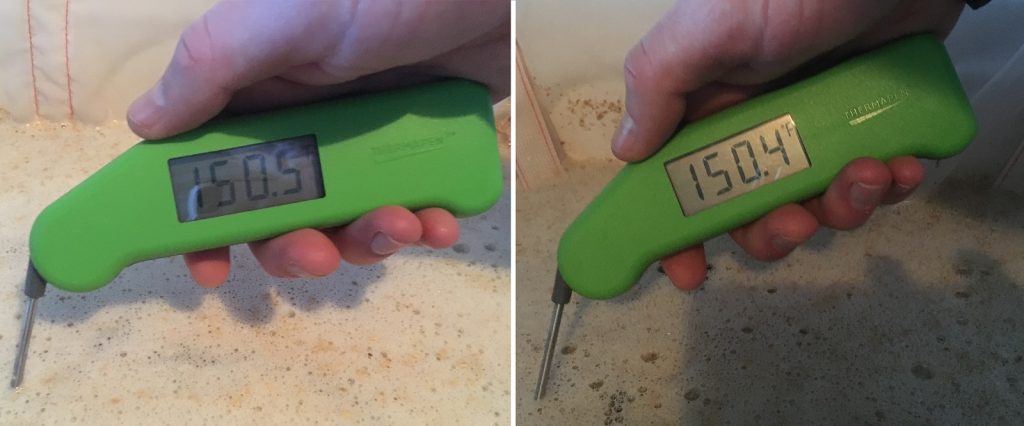

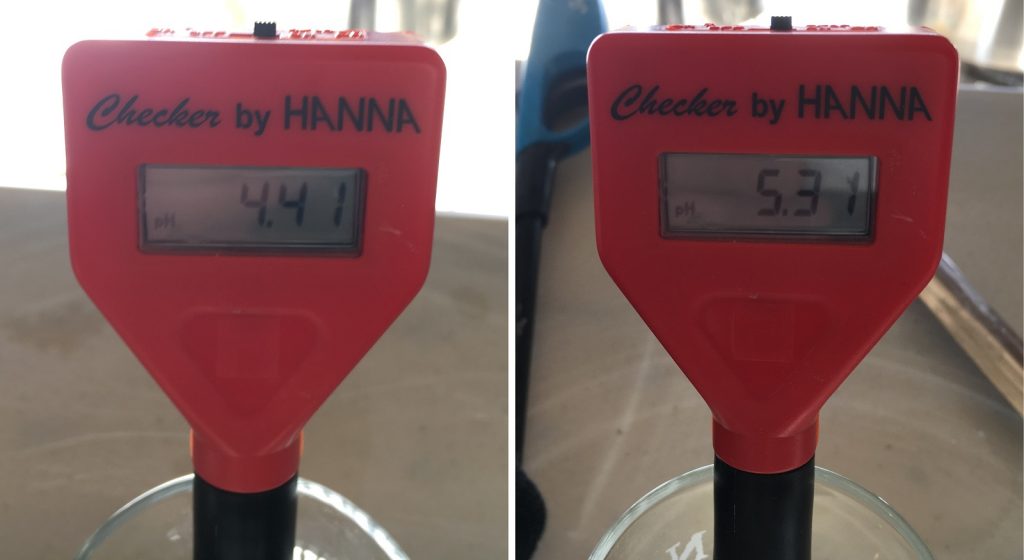

I took pH readings at 15 minutes into either mash and found the low pH wort was at pH 4.5 as predicted by Bru’n Water while the normal batch was sitting at a cozy pH 5.3.

After each mash finished a full 60 minute rest, I proceeded to collect the full volume of sweet wort using the no sparge method.

Both worts were boiled for 60 minutes with hops added at the times listed in the recipe.

Out of curiosity, I pulled samples for pH measurement from the worts as they neared the end of the boil and noticed both experienced a very slight drop.

At the conclusion of each boil, the wort was rapidly chilled to slightly warmer than my currently chilly groundwater.

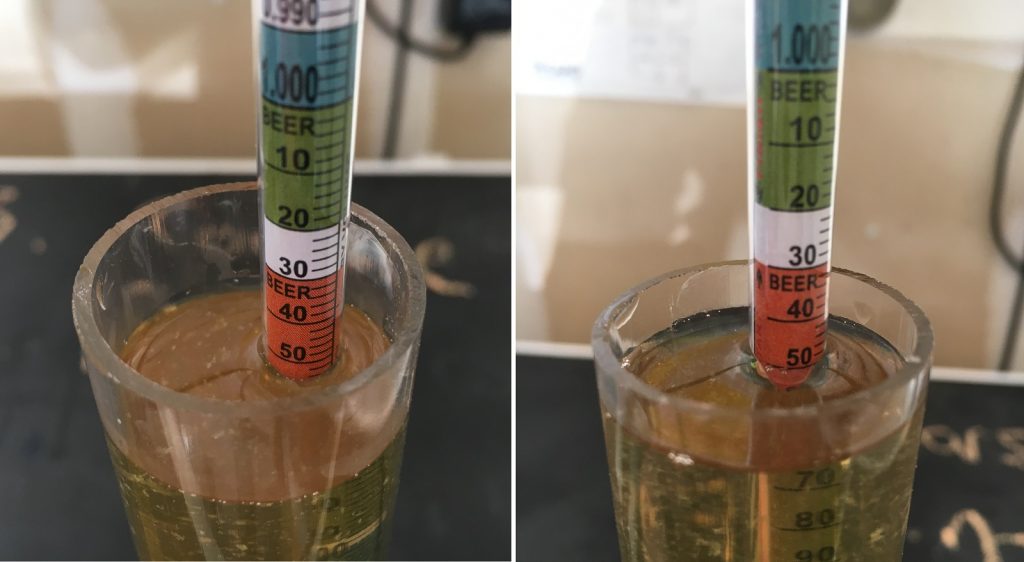

Hydrometer measurements at this time revealed the low pH wort achieved a slightly higher OG than the normal wort, which went against my expectation that low pH would hinder mash efficiency.

I racked the chilled wort to corny keg fermentors and placed in my cool chamber to finish chilling down to my target fermentation temperature.

I returned a couple hours later and found both batches had stabilized at my desire 50°F/10°C. After decanting the supernatant from the cold crashed started, I split and pitched equal amounts into either fermentor. I also added 10 drops of Fermcap-S to both batches in hopes of staving off a crazy blowoff. The beers were both happily bubbling away when I checked on them 24 hours later.

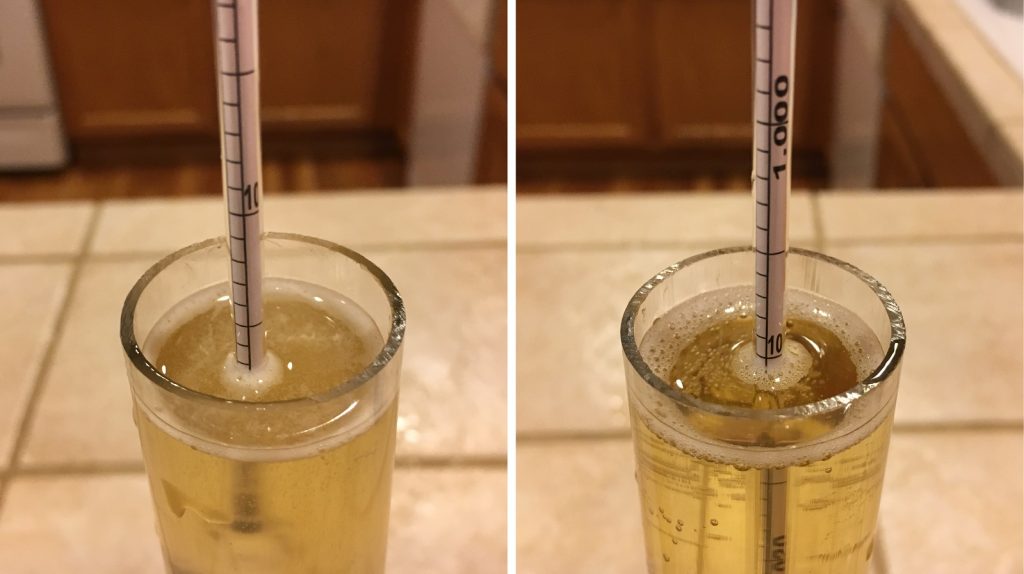

Hydrometer readings 7 days into fermentation showed the beers still had some fermenting to do, so I raised the temperature to 56°F/13°C to encourage complete attenuation. Subsequent hydrometer measurements taken over a few days 3 weeks later confirmed FG for both batches had been reached. Interestingly, the difference in FG between the batches was similar to the difference in OG, making me wonder if perhaps low pH encouraged increased extraction of unfermentable sugars.

I took final pH readings at this point and was quite startled to find out that both had settled at a very similar spot.

With the beers finished fermenting, they were pressured transferred to serving kegs then cold crashed, fined with gelatin, and carbonated.

When it came time to present the beers to tasters for evaluation, both were clear, carbonated, and looking quite tasty.

| RESULTS |

A panel of 22 people with varying degrees of experience participated in this xBmt. Each taster, blind to the variable being investigated, was served 2 samples of the normal pH beer and 1 sample of the low pH beer in differently colored opaque cups then instructed to select the unique sample. With the given sample size, a total of 12 (p<0.05) correct selections would have been required to achieve statistical significance, though only 7 tasters (p=0.64) chose the different beer, just about what’s expected assuming tasters were picking at random. These results indicate tasters were unable to reliably distinguish a beer produced with a lower than recommended mash pH from one produced with a normal mash pH

My Impressions: My experience on multiple triangle tests with these beers was the same as the xBmt participants, no better than what could be accounted for by random chance, which was very surprising to me as I’d developed a strong belief they’d be easy to distinguish based on the results of previous water chemistry xBmts. The beers were good, though I seem to pickup a noticeable sulfur note whenever I ferment with WLP838 Southern German Lager yeast that leaves me longing for the cleaner lagers I make with Saflager W-34/70.

| DISCUSSION |

A difference of pH 0.88 may not seem like much on the surface, but considering the pH scale is logarithmic, such a difference means the low pH mash was nearly 9 times more acidic than the normal mash. Putting it this was makes the results of this xBmt, that tasters were unable to reliably distinguish the low mash pH beer from the normal mash pH beer, a tad more more interesting.

The first thing that comes to mind are claims regarding the impact mash pH has on beer character, namely that crispness is associated with lower pH while higher pH can produce “flabbiness.” This presumes mash pH in some way carries through to the finished beer, which was not demonstrated in this xBmt. Not only did a beer that had 19 mL of lactic acid added to the mash taste the same as a similar beer without acid, but they ended up at nearly the same post-fermentation pH, which supports the idea that yeast stops working once beer pH is outside of the optimal range. This might explain why the low mash pH beer finished with a higher FG, the yeast simply puttered out once the pH floor was hit, suggesting fermentation serves as an equalizer or sorts.

If the observed differences in OG and FG between the batches are are indeed a real function of the variable, it provides evidence that extraction may be negatively correlated with mash pH, whether it effects flavor or not. Interestingly, every prior water chemistry xBmt that achieved statistical significance involved differences in mineral composition. With this in mind, if reports I’ve heard of a certain commercial lager brewery mashing with a low pH are true, I’m compelled to believe they do so not for purposes of flavor, but perhaps the behind-the-scenes impact it has.

The fact I genuinely couldn’t taste a difference between these beers coupled with the amount of lactic acid required to achieve such a low mash pH, I’ve no plans to change my current process of mashing between pH 5.2 and pH 5.6. I’m now more curious than ever to continue exploring the limits of mash pH and the impact it has on beer.

If you have any thoughts about this xBmt, please do not hesitate to share in the comments section below!

Support Brülosophy In Style!

All designs are available in various colors and sizes on Amazon!

Follow Brülosophy on:

FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM

If you enjoy this stuff and feel compelled to support Brulosophy.com, please check out the Support page for details on how you can very easily do so. Thanks!

53 thoughts on “exBEERiment | Water Chemistry: Evaluating The Impact Low Mash pH Has On A German Pils”

Thanks for another great article. This confirms to me that, while mash pH is important, you can get away with some mistakes.

With my first ever AG brew I attempted to get my head around water chemistry and failed. I ended up with a pH of about 4.5 and experienced a similar result. The mash went fine but the beer finished quite a few points higher than the expected FG.

Wow, very weird. Do you have any idea what the mash conversion efficiency was on the two batches? I had anecdotally been thinking that my beers that had accidentally gone up closer to 5.6 in the mash had been getting better conv. efficiency, but I think that was just coincidence now, as I am doing an NEIPA right now that I just got 95% conv. efficiency on with a mash pH of 5.48.

Anyway, I wonder if the yeast is able to adjust the pH of the wort to its desired pH within reason? Not trying to anthropomorphize yeast, just offer a suggestion for why the final pH was similar. It seems like the final pH being the same would result in the same flavor UNLESS the anion from the acid chosen has a strong flavor component (eg lactate from lactic acid, phosphate from phosphoric acid, sulfate from sulfuric acid, chloride from hydrochloric acid) or unless flavors are extracted from the mash at different pHs. I am looking forward to your high pH version!

It’s amazing there was no mouth feel difference to pick out with FGs of 1.011 and 1.017. Sort of makes you wonder where chewy/heavy mouth feel comes from if not from residual sugars.

In my experience, the FG has very little to do with the mouthfeel of a beer unless you really ferment it down to super low levels using enzymes or unless there are simple sugars left (which taste sweet and give the impression of a thicker beer.)

It’s definately something brulosophy has debunked to some extent with their mash temperature experiments. I’ve traditionally chosen a less attenuating yeast along with a higher mash temp (to get more unfermentables/sugar in the wort) and ingredients like oats/flaked barley when I wanted a fuller mouthfeel beer but it certainly seems like that’s not the case after their experiment results. I think things are becoming more muddled, confusing and unknowable rather than more clear with some of these results.

ha ha! I agree. It IS nice to know that you can screw up a lot of things on a beer, and it has a good shot at turning out just as good!

Yeah, I guess mouthfeel is more viscosity than density. Kinda makes sense.

A side question. How has been your experience with your Ph meter. I am in the market for one.

The checker by Hana was annoying, constantly had to manually calibrate it. The final pH reading is using my new thermoworks meter, auto calibrates, been awesome so far

Not trying to derail this, but I’m curious, do you still check with a couple standard solutions (say pH 4 and pH 7) to make sure it is bang on? Just wondering. I don’t bother checking pH during brewing, but I work in a lab and I always check (and calibrate if needed) the pH meter before using. Paranoid.

Two point calibrated before every reading yeah.

which thermoworks model do you recommend? they have several and pretty good range on $

I have the 8689 which I love, think Marshall has that same model. A few of the other writers have the 8100 which I believe they like but can speak to it. The auto calibration on the 8689 is so great

I’ve had trouble getting my 8689 calibrated and TW suggestions haven’t help either. I just had the Apera PC60 delivered. In addition to pH, it also tracks EC, Salinity, TDS, and Temp. I’m curious to pit them against one another.

Thermoworks 8969 is on sale right now for $69

This is really interesting. I hope you are going to do the opposite experiment now by test 5.2 and something closer to 6. Thanks for the great work.

We’re definitely going to test higher ph

In my own anecdotal experience – and the experience of BJCP judges on several of my previous beers – higher pH beers tend to impart a bizarre astringency. When I actually started to adjust pH with lactic acid, I noticed a sharp difference in my enjoyment of my home-brew. Also, my vorlauf produced clearer wort in a shorter time with lactic, as compared to no pH treatment.

already done it i think? https://brulosophy.com/2015/04/06/water-chemistry-pt-1-mash-manipulation-exbeeriment-results/

That exbeeriment was fully adjusting water, both pH and minerals

This is interesting, especially the theory on the pH floor being what kicks yeast out of production. I’m assuming that an exBeeriment is on tap to go the other way, say 5.2 to 6.0, as this might test that variable. If the yeast starts on a wort that is a touch more basic than normal will it ferment lower?

In a somewhat related “test” I dosed my bread dough with a bunch of lactic acid to make a cheaty SourDough. With just a bit it was fine when I went with more the bread never rose, the yeast just gave up. It was dough so I don’t know what the actual pH was (I don’t have a dry probe) but I didn’t go crazy. It was 1/2 again the dose that produced a very slight tang. I often use buttermilk for this and it works fine.

My suspicion is that by adding acid I made a hostile environment for the yeast where with a culture like buttermilk a lot of the acid is produced after the yeast has done it’s thing since the culture is producing the acid and it’s not all there at the start.

But?

another awesome exbeeriment. can you guys please post specific water additions you are making to your RO water as part of the overall recipe, for us non-water chemistry experts? such as, added X grams of Gypsum, etc.

For 8.75 gal of RO water Bru’n water had me add 3.1 grams of both gypsum and CaCl to hit my target profile.

I’ve been looking at pH meters a lot, but it seems to get anything that’s anywhere near accurate enough you have to spend a fortune. I believe that Hanna pH meter’s accuracy is +-0.2pH? Is that good enough? It’s clearly accurate enough to show us generally what’s happening, but when you’re talking about that slight pH drop after the boil, does it really mean anything?

Also, sample temperature seems to have a huge effect, and trying to get your sample to the exact right temperature while the mash is happening for me is very difficult. When you checked your pH during fermentation it reads 55-56, is that what that meter is calibrated for? From what I can tell ATC does not mean what you think it means with pH meters i.e. different chemicals would have different correction factors.

Samples for the Hanna were chilled to ~60 which is the temp I calibrated it at, not sure the Hanna has auto correct.

The thermoworks was calibrated at 60f and autocorrects on temp. I’m pretty comfortable with the final ph readings being close to it’s calibration temp.

When I looked into it what I came away with was that you really need accuracy to about .01, because you want your X.X to be solid. Not sure what a “fortune” constitutes. I looked for awhile and found a lab grade meter for water testing new on eBay for $60. ATC auto calibration and if I spend the $ for other probes it does a number of other functions like dissolved O2. Probably won’t go there because that probe is a lot more than I paid for the meter!

The cheapie pocked ones (I tried two over the years) are both a PITA to calibrate, not very accurate, and eat batteries. What finally pushed me over the edge was that I started to do some preserving and needed to check the pH of brines and sauces so it became a “multi-tasker”.

I’ve been getting good results mashing at 5.1. Great efficiency as well as attenuation. Temp is usually 148F. Beers dry out the way I want them to; I get full mouthfeel from other variables (no oats or other adjuncts whatsoever though).

What was your experience with the boil on the low pH wort? It is always stated that the pH for best protein coagulation is 5.2.

Maybe every yeast strain has a preferred finishing pH that it likes to settle at no matter the starting pH? The finishing pH probably ends up being to style. For example, maybe most pilsners end up around a pH of 4.15 like in this experiment.

That seems totally reasonable

Very insightful study… i have on a couple of occasions mashed at 4.8 pH(mainly because i don’t have the salts for water adjustments). I found that the final beer pH was around 3.5 and tasted a bit too acidic

I’ve been doing a lot of research on Bohemian Pilsner lately since I plan to brew one in a couple weeks. From what I’ve read, a few sources state a low mash ph of 4.8 is required to create the softness and smooth bitterness associated with the style. I wonder how important it “actually” is now. I’m sure the hop utilization is affected by this but I wonder if I’d be getting abnormally low attenuation…

How do we account for quick sour beers made with ale strains finishing say around 1.010. The starting ph of the wort is much lower than the experiments. I just did a quick sour and brought it down to a ph of 3.27 with lacto for 48hrs. Then pitched Wyeast 1318 and it fermented down to 1.009. There must be more unfermentables (or less fermentables) produced by the low ph mash that cause a higher gravity rather than the yeast giving up the ghost due to ph?

Hi guys! I wanted to say I appreciate all the xbmt’s you do, but I want to talk about you using kegs as fermenters in one of the photos above as I’d like to start doing this. When fermenting in kegs, what volume of wort are you fermenting? Using the ‘gas in’ post as the blowoff? Liquid out dip tube shortened to account for trub? What is your finished volume after transferring to the serving keg? Adding gelatin to the serving keg before racking and then burping with co2? Please tell me more! There is a good deal on 4 pin lock kegs with disconnects online. Though I prefer ball lock, I am thinking of buying them to use as fermenters.

I ferment pretty close to the top, I use fermcap-S and a blow off tube on the gas in post. I don’t shorten the dip tube but many do. I simply bend it so it rests up against the side of the keg on the advice of Greg. Finished volume is like 4.5-4.75 gal. You can crash in the ferm keg and fine or fine in the serving keg once cold if you like

Lactic acid has a pKa of 3.86. It therefore becomes difficult to make the pH change much with lactic acid as the pH approaches 3.86. The pKa or other buffering seems the most likely reason why the pH ended up the same.

Nevertheless the taste result is surpising. But the appearance seems to be different. Were the tasters blind to the appearance?

Yes always blind

I’m surprised that the greater FG did not result in a taste difference. I submit that the difference in FG is partially due to the difference in OG and the lower mash pH impairing the amylase enzymes’ ability to break down the maltodextrins into maltose.

FWIW, I have been skeptical for some time that mash pH has much effect on the final pH, but this experiment is extreme. Perhaps a less acid producing yeast might have produced a bigger final pH difference.

I’d like to see the same experiment but with a beer that had roasted grains. In my experience that’s where I’ve seen a big difference in favor for different pH levels.

I know I’m late to the party here, but what’s interesting is that I’ve done Berliner Weisse and Gose beers where the pH at the start of fermentation is in the low 3’s…in fact I’ve made two that started in the high 2’s, the lowest was 2.8. Most of those were fermented with German Ale/Kolsch yeast, which is known to work well in low pH environments….but I’ve also fermented a Gose recently with a starting pH of 3.2 using good old US-05. So it can’t be that yeast stops working at a certain pH…but perhaps it stops after the initial pH drops by a certain amount?

I think it’s more likely the mash extracted something different

“The first thing that comes to mind are claims regarding the impact mash pH has on beer character, namely that crispness is associated with lower pH while higher pH can produce “flabbiness.” This presumes mash pH in some way carries through to the finished beer, which was not demonstrated in this xBmt. Not only did a beer that had 19 mL of lactic acid added to the mash taste the same as a similar beer without acid, but they ended up at nearly the same post-fermentation pH, which supports the idea that yeast stops working once beer pH is outside of the optimal range. This might explain why the low mash pH beer finished with a higher FG, the yeast simply puttered out once the pH floor was hit, suggesting fermentation serves as an equalizer or sorts.”

I don’t think this is what’s going on. Most microorganisms engineer their environment, which often excludes the activity of microorganisms that will also compete for the available resources. LAB make lactic acid because many other organisms can’t thrive there; yeast makes alcohol because many organisms can’t tolerate it. As you would expect of a creature made by evolution, it often has more than one defense (acid and alcohol makes a narrower class of organisms that will compete than just one of these.) Yeast likes a pH around 4.0 (give or take) and most strains acidify their media until it’s where they like it. They don’t peter out when pH is hit–they peter out when they’re out of food–but they stop making acid once they’re cozy (alternatively, the acids they make could be very weak, so they stop acidifying at relatively high pH.) The high FG of the low pH sample may come from low beta amylase activity, which makes maltose, so the alpha amylase dominated conversion, making less fermentable wort.

As far as I know, the study of pH and beer has mostly been on standard 5.2-5.5pH mash versus high pH mash, over 5.6; this is the first thing I’ve ever seen where someone deliberately lowered a mash under 5.0.

I read somewhere (can’t remember where) that while pH 5.2-5.5 may be optimum there was a lower decrease in conversion at lower pH than on the higher pH side. So it was suggested that if you weren’t on target it was better to be lower than higher. I guess having a lower pH might also delay the point at which the pH rises sufficiently to start extracting astringent tannins from the grain.

Because of this, and all the stuff about oxidation, I went through a phase of adding a small amount of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) to my mash. I’d certainly get a lower mash pH, maybe 4.5 but have no idea if its anti-oxidant properties helped in any way. I could detect absolutely no effect on the flavour of the beer. I no longer do this simply because I think it was a pointless exercise.

Kai found some interesting stuff about low ph slowing oxidative browning in beer, I didn’t really observe that in this xBmt though.

The oxidation topic is definitely on the list!

Hey, would you use this water profile Ca 50 | Mg 0 | Na 8 | SO4 50 | Cl 50 | HCO3 16 | for all pilsner recipes or is it a custom one for this xbmt? Cheers!

Hey guys,

I just want to point out that kettle and mash souring will produce a wort pH in the low 3’s. It may affect fermentation in some yeasts but not all. Also for some particular styles, e.g. Bohemian Pilsner, a mash pH of 4.8 is advised.

One advantage of low mash pH is that you will extract fewer tannins, leading to a less astringent wort and a better shelf life in the bottle. Disadvantages include lower levels of alpha acid isomerisation and should technically decrease extraction from the grain though that wasn’t observed in this case.

In saying that, I would stress that almost all brewing resources recommend a mash pH between 5 and 6 but ideally 5.2-5.4. This is because it is where you are going to get the best amylase activity. Depending on your reasoning for lowering the pH, I would suggest to target 5.2 in the mash and then adjust your wort in the kettel if necessary.

As always, I would recommend using caution when applying rule of thumb measurements to pH adjustment as you will more than likely have a vastly different buffering capacity in your water meaning a much greater or lesser adjustment is required.

I think you also have to consider mash temperature along with mash pH. When talking about alpha and beta amylase conversion. Especially when doing a stepped mash.

I start my Kölsch mash at 122F for 20 minutes before raising it to 152F for the remaining time. Favoring a ‘soft’ water profile. A mash sample taken 30 minutes into the mash and cooled to 75F was 5.18 pH.

I think the reason that the addition of acid having no effect is residual hardness (presumably due to bicarbonate). It is possible that the addition of acid was not in sufficient quantity to overcome the buffering effect of the hardness…

Thanks for this exberriment, Jake.

Searching for this because I had a brain fart during my last lager brew on the mash.

For some reason I was trying to get to 4.3 instead of 5.3. I didn’t realize the error until I had added copious amounts of lactic acid.

I was feeling proud of myself with a higher OG than expected however my FG turned out 3 gravity points higher than I expected.

It seems the same happened here so the unfermentable sugar theory makes sense to me.

Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for another great xBmt. Reading your discussion you say the two beers end up at a similar PH post fermentation but a higher FG in the low mash beer which is probably down to yeast. I wonder would there be a difference in gravities if the PH level was adjusted during fermentation and would it change the taste or ABV? Cheers

I’ve just done the same thing with a NEIPA (using a new kit and a new water supply). Mash pH a little lower and an FG a few points higher than expected. It does taste slightly sweeter than I like, but I might just be paranoid since it didn’t attenuate as much as I hoped. I wonder if this method of of using low pH could be used in making a tasty small beer?

It’d be neat to repeat this experiment with a pH of lower than 4.2. Protein-converting enzymes have a comfortable pH range where they operate of 4.2-5.3 (http://howtobrew.com/book/section-3/how-the-mash-works/the-protein-rest-and-modification). With a more extreme low pH you might see more drastic differences in the beer.